Radiohead’s new release “Burn the Witch” marks the end of a long period of silence from the band. It is a patient, driving piece with an engaging form that seamlessly incorporates orchestral string instruments into the music. Often when rock songs use strings, they feel like an extra topping daubed on at the end of the process, but in this case, the strings are one of the core, integral, and defining elements of the song. And they don’t get a break: They are the first thing we hear at the beginning, they play throughout the entire song, and they are the last thing that’s left ringing in our ears at the end.

As an arranger myself [ed. note: and the instructor of Soundfly’s “Orchestration for Strings” course!], I often think that if an ensemble is playing throughout an entire song, the listener’s ears will get tired. Arranging moments without the orchestra can be engaging and make the moments where they are playing more striking. But that’s the wonderful thing about music — just as preconceived notions start to solidify, something comes along to smash them down. In the case of “Burn the Witch,” Jonny Greenwood (I assume he arranged the parts, given his recent orchestral work) keeps the strings engaging throughout the work in a few primo ways. Let’s take a closer look at some of the techniques he uses.

Quick disclaimer before we move on: It should be noted that I agree with the sentiment “writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” neither are pointless, redundant, nor impossible, but both are challenging, can be unwieldy, and ultimately, nobody has any authority. I haven’t seen the scores for “Burn the Witch,” but these are some of the things I noticed when listening. Feel free to agree or disagree in the comments below!

The Col Legno Bowing Technique

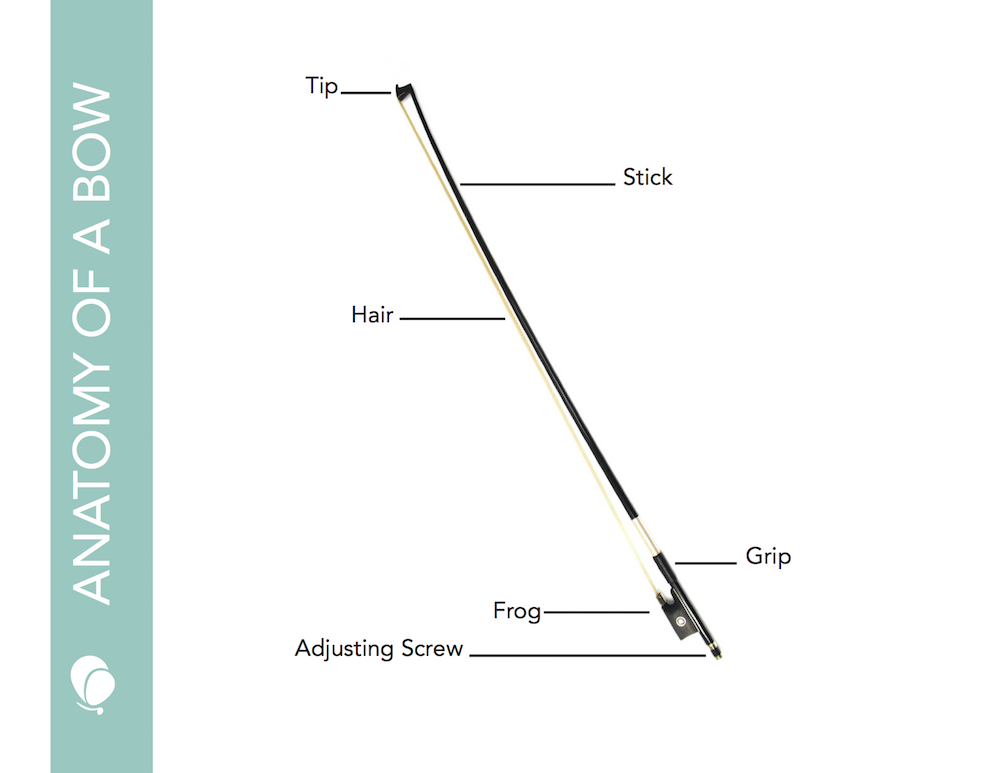

Greenwood explores the full technical palette of the string section and, in so doing, paints a number of exciting colors at choice moments throughout the song. The driving, frantic, percussive sound we hear at the beginning and throughout the song that sounds like a mix of arco (bowing the string) and pizzicato (plucking the string with the finger) is an effect called col legno battuto which in Italian means “hit with the wood.” It is an instruction that signals the players to turn their bows over and strike the string with the back (wooden part) of their bow. At the same time, it sounds like this percussive technique is mixed in with some members of the string section playing staccato with the horsehair side (the regular side) of the bow to pronounce the harmony.

In my opinion, it is the col legno effect that is the most striking element of the song’s arrangement. It’s an effect that isn’t heard that often in orchestral music, let alone pop music. It abstracts an already special treat (strings on a rock song) and hooks in listeners with a familiar yet unfamiliar sound. It turns the strings into part of the percussion section, which allows them to remain useful and engaging throughout the whole song.

The Legato Break

At around the 1:37 mark we get a striking break in texture. The band drops out, as do the percussive, col legno strings. We hear some lower members of the string section still chugging along, but the violins and violas contribute soaring, legato parts on top — closer sonically to what our ears tend to expect from a string section. The parts lilt and unfold around the vocals and seem to be mixed just as loud as — if not louder than — the vocals. This democratic move shakes off the usual sonic hierarchy we hear in pop/rock songs where the singer is the main event, followed by the guitar player, with the bass, drums, and anything else appropriately tucked under.

The Dissonant Harmonics

Another striking textural and harmonic change starts around the 3:20 mark during the sacrificial, “Wicker Man” climax. The strings start creating more of a “squawky” sound. Dissonant notes that we haven’t heard before begin jumping out of the arrangement like microwave popcorn at its tipping point. The high strings seem to be hitting harmonics — certain nodes along the fret board that when lightly touched with the finger will produce a ghostly, thin tone, higher in register than the usual note produced when the finger is fully depressed. They also seem to be playing ponticello (bowing closer to the bridge) which gives them that dry, harsh, breathy timbre in an already harsh register of the instrument.

Playing with Registers

The movement throughout the registers of the string section as well as the roles assigned to the different registers is another thing that keeps the string parts engaging. Although the strings are playing during the entire song, we experience them in (seemingly) four broad textural iterations: the col legno parts; the chunky, staccato driving pulses; the lilting, legato parts in the string break; and the high, squawky freakout harmonics at the end.

The col legno is generally confined to the upper-mid register of the section. This sits nicely with the rest of the band and feels like part of the percussion section. The chunky, staccato pulses are for the most part given to the lower members (cellos) and give the parts some weight and intensity when they come in on the choruses (in contrast, the contrabasses seem to be holding long, low notes underneath these moments). When the string break comes, the lilting, legato parts are again assigned to the upper-mids (now no longer playing with the wood of their bows). So while Greenwood stays in the same general register, the texture is suddenly drastically different and something we haven’t heard yet in the song.

The harmonics and dry, harsh playing at the end gets us into the extreme high register of the violins, which makes sense with the imagery before us. Something terrifying is coming in the video’s “Trumpton”-esque claymation, and as the string parts rise, so do the little clay flames up the Wicker Man.

The movement throughout the different registers prevents the listeners ears from tiring. If the violins were to play in their high range the whole time it would be exhausting, if the cellos were chugging along through the entire song we would get bored, but at a few decisive moments we get changes in texture and register that pique our ears, keep us engaged, and build a solid structure for the song to be burned alive within.

Further Listening

If you’re interested in exploring some of these techniques in more depth, here are a few of my favorite pieces that use col legno, harmonics, staccato, and the same sort of register movement as “Burn the Witch.” Do you have any you would like to contribute in the comments below?