+ Take your modern jazz piano and hip-hop beat making to new heights with Soundfly’s new course, Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production!

By Brad Allen Williams

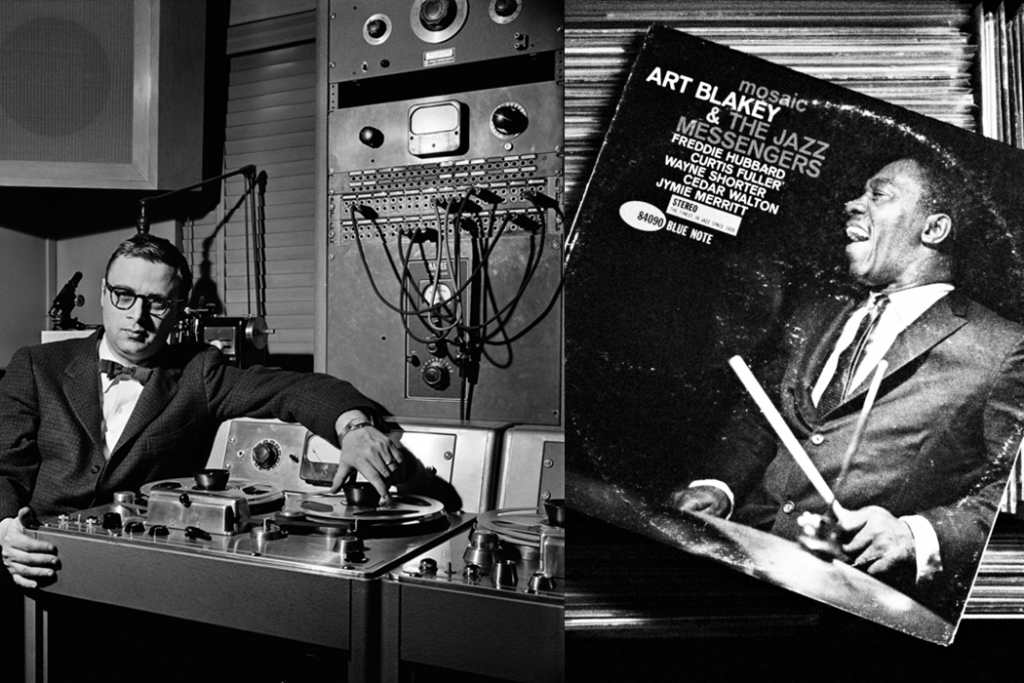

Rudy Van Gelder died 25 August, 2016 at the age of 91, having made some of history’s most enduring sound recordings. If you’ve explored the variegated tapestry of 20th century recordings lumped together under the criminally reductionist banner of “jazz,” you probably know the name. If you’ve dug through crates and slid records out of jackets to look for the distinctive block-letter “RVG” in the dead wax, you understand that a name can be synonymous with an ethos of record-making — one that, when entwined in double helix around a complementary ethos of composing and performing, formed the DNA of some pretty significant recordings.

With a tiny sapphire stylus, Rudy Van Gelder scribed a sizable chunk of the Rosetta Stone of American music, translating the genius of artists like Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, John Coltrane, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley, and scores of others for the masses.

Rudy Van Gelder’s boyhood interests in amateur radio and trumpet naturally evolved into a passion for high fidelity audio. He began recording friends in his parents’ Hackensack home at age 22, and in 1959 (seven years after beginning a fruitful association with Blue Note Records), he quit his day job in optometry and opened a purpose-built studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. It was here that he recorded seminal works for Prestige, CTI, Verve, and Impulse!, including Coltrane’s landmark A Love Supreme, as well as nearly every classic Blue Note side before 1967.

Just perusing through the discography of Van Gelder Studios is enough to induce a headache!

The first voice you hear on the reissue of Art Blakey’s Moanin’ is trumpeter Lee Morgan’s; the second a distant Van Gelder over studio loudspeakers.

“Rudy?”

“Yeah.”

“I’m not standing too close when I play the ensemble am I? You mean when I take my solo?”

“Yeah, you moved in, you were a little too close there.”

“Yeah, well, I’ll step back a little ‘cause I come in very loud.”

This conversation is a window into a process. Van Gelder recorded his most important 1950s and 1960s work direct to either mono or 2-track stereo tape (or both simultaneously). This technical and aesthetic high-wire act combines tracking and mixing into a simultaneous procedure in which numerous microphones are balanced by the recordist live to tape as the musicians play. To do this successfully, performers and mics must be positioned optimally in the room and equipment must be in impeccable repair and alignment. But most importantly, the recordist has to have it together from the first beat, because with artists of Blakey’s caliber, the very first run-through could be the final take.

There is no “undo.” Any decisions (or non-decisions) are permanent. Equipment failure or human error could mar or render unsalvageable an otherwise brilliant performance. High stakes, immense responsibility, and innumerable pitfalls demand clear judgment, foresight, decisive action, and quick but measured reaction. This is how Rudy Van Gelder made records in the 1950s and ‘60s.

But despite all of this, the recordings are so engaging, with focus so superbly directed to the artists, that it’s easy to forget that they’re Rudy Van Gelder performances as well. Although the record and mix were complete as soon as the last cymbal decayed, Van Gelder was no Lomax-style documentarian. Like so many of the artists he recorded, Rudy’s work had personality, and his performances were distinctive and individualistic for better or (occasionally) worse. Charles Mingus famously preferred not to record with Van Gelder, alleging that “he tries to change people’s tones… the way he sets [a player] up at the mic, he can change the whole sound.” And although he was famously opaque about technical details, most agree that Van Gelder probably incorporated some then-unconventional techniques, such as DI capture of Hammond organs in combination with microphones on the Leslie speaker, in the case of the wild organist Jimmy Smith.

The title of Thelonious Monk’s “Hackensack” is a reference to RVG’s original home studio where many of Monk’s tracks (including this one) were recorded.

These clues suggest that Van Gelder was most likely guided foremost by the goal of achieving good-sounding recordings, as opposed to any preoccupation with literal verisimilitude or procedural dogma.

Secretive until the end (there’s an apocryphal legend that Mr. Van Gelder sometimes put up different microphones for photo shoots than he actually used on the sessions), we can only make informed guesses about what Van Gelder actually did. We know there are a lot of Schoeps M221b condensers in the photos (always with the windscreen installed!).

There’s a famous shot of him posed in front of two Ampex 300 1/4” tape machines and a mono Altec 4322c limiter. A pair of U47s are in the frame with a pensive John Coltrane in a photo from the Blue Train session. We hear a fair bit of room and spill on the records, suggesting that the musicians were most likely allowed to perform more-or-less together, with minimal isolation — an impression supported by the fact that there are certainly no headphones in any of the session photos.

But in the end, these are mostly superficial details of process, and to focus on the technical would be to miss what makes Van Gelder’s work great. So immediate are the recordings that even the occasional defects — the clipping distortion on the bass drum of an enthusiastic Idris Muhammad (née Leo Morris) during the breaks of Reuben Wilson’s original 1969 recording of “Hot Rod,” for instance — seem to become powerful signifiers of the moment and its authenticity. And when the flaws in your work become features, you are unquestionably an artist.

For a deeper look into Van Gelder’s mind, check out this interview with producer Michael Cuscuna.

RIP RVG.

Don’t stop here!

Continue learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Ryan Lott, and the acclaimed Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.