This is the fourth instalment in our series on How Successful Musicians Practice. If you’re just joining us now, this series asks professional and semi-professional musicians performing and recording with all kinds of groups how they practice and what helps them stay organized.

We’re getting to the heart of what it takes to grow your musical skills and improve your capabilities simply through dedicated practice. It’s safe to say that everyone is different. There are many paths an artist can take to reach his or her goals, so we’ve asked the following musicians about their routines, rituals, and their personal practice philosophies (PPPs).

So far, we’ve interviewed a handful of composers and songwriters, drummers and percussionists, and string players like guitarists, a violist, and a bassist. Now we’re introducing you to the practice routines of the horn section. Hopefully, these interviews can serve as references and sources of inspiration for aspiring and career musicians.

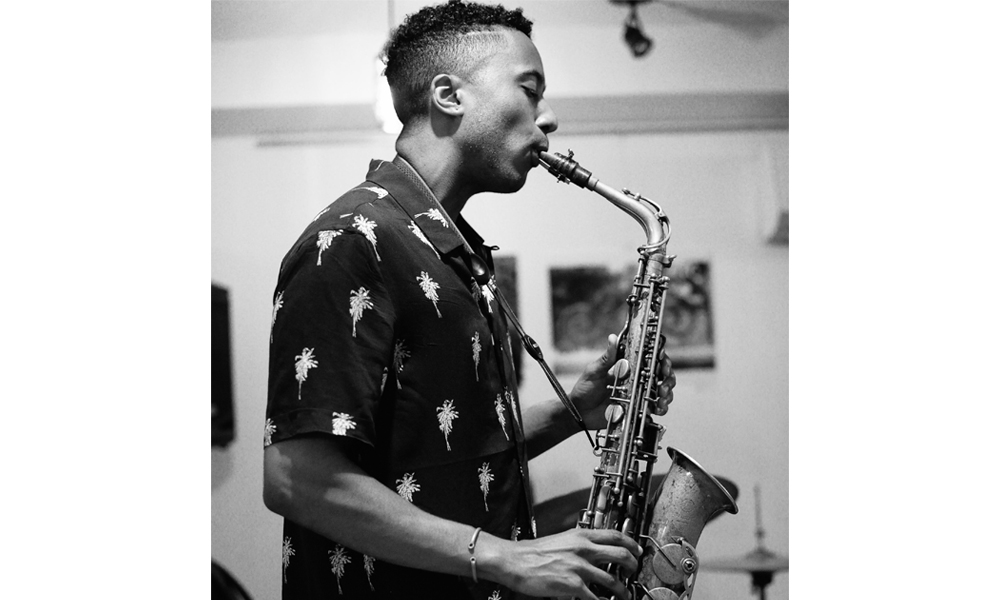

Braxton Cook (Saxophone, Vocals)

Braxton performs with Christian Scott, Wynton Marsalis, Ulysses Owens, and Jon Batiste.

I practice about three to five hours a day, every day that I’m not traveling. And that’s three to five hours combined either on my main instrument (alto sax) or on flute, vocals, and piano. I mainly practice at my apartment now and start by warming up and stretching. Relieving tension is the most important thing when trying to get the best sound you can. I like to warm up my voice before everything else, typically in the shower. I loosen up my tongue, throat, and neck first, then I get to warming up on my saxophone by playing scales and long tones. Showering and drinking coffee are a must in the morning for me.

My biggest obstacle in practicing regularly is traveling. When I travel a lot, I tend to get out of rhythm. I combat this by practicing and honing other skills. Obviously, I can’t take my saxophone out on a plane or a bus, so I like to listen to and transcribe music. This helps train my ear and helps my sight reading. Sometimes I only practice singing when I’m on the road, which can help me establish a deeper connection with things I play on my horn.

My breakthrough moment in the shed came when I was in high school. I used to have this cedar closet in my basement where no one could hear me, so I used to just improvise freely with a metronome at the end of my practice sessions.

This one time, I distinctly remember getting into this flow where my ideas and my fingers worked in conjunction with one another. It was a feeling I’d never felt before. I was in this zone where I was truly improvising, yet still executing cleanly. But more importantly, I was really singing what was coming through my horn. It finally felt like an extension of my voice as opposed to this metal thing that I blew air through.

When I came upstairs after my session, my parents noticed something was different. My dad said, “You sounding good down there, boy.” At first, I thought, “Oh God, they heard that.” But then I realized that something definitely clicked. The affirmation from my dad that I was on the right track after letting go and really being vulnerable was so inspiring. I was hooked on that feeling.

My PPP

Practice is definitely a daily routine thing for me that makes me feel like I’ve accomplished something for the day. It makes me feel productive. But more importantly, when I’m really practicing effectively, I find that I’m tackling my biggest fears and biggest musical insecurities (i.e., air, my range, or my intonation).

Most often, people practice things they already know well or material with which they feel comfortable. But I find that I grow most when I’m working on my weaknesses, and these things generally don’t sound good to people. For instance, I know working on intonation in my upper register is something that’s both exhausting and intolerable to people listening!

However, you have to block out the self-conscious part of your mind (your ego) and allow yourself to be vulnerable so that you can honestly assess what’s good and what needs work. Sometimes, the ego doesn’t allow us to get better because we’re afraid to let just go and sound bad.

I think you have to be willing to sound horrible to really grow. If you only play what you know, you’re going to progress at a much slower rate than someone who’s constantly working on parts of their playing that need development. You see this in the gym all the time: people work on muscles that are already quite pronounced and strong. They want to skip over their weaker points because it makes them “feel bad.” This is just the ego trying to protect itself. We have to let that mentality go in order to improve.

+ Learn more on Soundfly: Stretch your rhythm writing skills while tightening up the section. Our newest free course series, Get into the Groove starts with a course on Writing Funk Grooves for Drums and Bass.

Nicholas Payton (Trumpet, Vocals, Keyboards)

A Grammy-award-winning recording artist, Nick has worked with Jill Scott, Roy Haynes, Kenny Garrett, Herbie Hancock, Nancy Wilson, and Ray Charles.

Sometimes, I can go days or weeks without real practice. At the most, I never practice or play more than six consecutive days a week, unless I’m on tour and it’s unavoidable due to scheduling. Usually, I have the tour laid out so it’s no more than six straight days of playing.

That said, on gig days, I’ve found that a warmup is more effective than a full practice routine. My full routine lasts about an hour. I practice at home, in my hotel room, or any other private space. Wherever it is, it’s not practice if it’s in front of people. That’s a performance. Solitude is more important than space, in this case.

When I practice, I focus on fundamentals: flexibility, dexterity, and most importantly, airflow. I rest for an equal amount of time as the exercise takes between each exercise. So if an étude takes 10 minutes to get through, I rest for at least 10 minutes before starting another.

Before I begin to practice, I think about what I’d like to accomplish and get out of my practice session then do some deep breathing to bring my mind to a quieter space.

Boredom is my biggest obstacle. Pacing oneself in both the long and short term can help, but I’ve found no cure for the boredom.

My PPP

Being in the shed is not enough. One must know how to practice to make great gains in the process. I practice to earn the right to make mistakes.

+ Read more on Flypaper: Got a gig coming up? Here’s our list of musts in order to make sure you’re fully prepared!

Jake Baldwin (Trumpet)

Jake has performed with Har Mar Superstar, McNasty Brass Band, and the Love Experiment. He came in third place at the International Trumpet Guild Jazz Division in 2010 and second place in the National Trumpet Competition Jazz Division in 2013.

How much do I practice? That’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it? I suppose it depends on what you consider practice. The trumpet is such a physically demanding instrument that even with an entirely free day and chops that feel good, I’ll probably only have two or three hours of horn-on-face time per session.

The brunt of my practicing, in reality, is me sitting there and thinking about a specific issue I want to address on the trumpet, or musically at large, and trying to work as much of that as possible out in my head before I even attempt to play it. I feel like this helps me be as efficient as I can with the time I have on the horn. It also helps me stay focused in the moment. I will say though, I try to never take a day off from playing. Even if it’s only for 10 minutes or so, I do my best to make sure that I practice some amount each day.

In my opinion, where you practice is just as important as what and when you practice. About six months ago, some friends of mine and I got together and rented out a building that used to be a schoolhouse. It’s got a lot of little rooms in it and a big gymnasium type of space. I used to practice at home, but I found myself getting distracted far too often.

Having a spot that’s designated as a place to put in work musically, or an office of sorts, has made my practicing 100 times more efficient and focused. Having a physical location to go to when I want to practice has helped make it a routine, not unlike going to the gym to work out. When I step through those doors, I know that it’s time to push all my distractions aside, (hopefully) put my phone away, and create something.

I try to break my practice time down into three parts:

1. Things I need to do

This includes my mental preparation, my daily warmup routine, and working on any music that I need to learn for upcoming projects or jobs.

The mental preparation comes from a story I heard about a professor who teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. Every morning before he plays, he allegedly looks in the mirror and says, “This is the best part of my day.” This really struck a chord with me and rings true on so many levels. I’ve tried to adopt that sort of mindset so that I can be in the best possible mood mentally before I sit down and play this monster of an instrument.

As for daily routine stuff, I try to get in at least a 30-minute warmup every day and just touch on everything I have to do for that day to make sure nothing is totally out of whack. If something isn’t working, I’ll take a few extra minutes and focus on that until it works itself out.

Getting a good warmup on a brass instrument every day is honestly the only way to have any sort of physical longevity. If I have music I need to work on, I’ll try to incorporate it into my warmup, meaning I’ll try and use parts that cover the stuff I need to warm up (flexibility, range, articulation) and make it into an exercise. This is all part of my quest to be efficient.

2. Things I want to do

This one is pretty self-explanatory. If you’re a working musician and you’ve worked on the things that you need to do your job well, now it’s time to work on the things that make you an artist.

This part of my practice time is usually spent hitting one element pretty hard. It could be something as concrete as working on a pattern I like and taking it through all the keys, or it could be something more esoteric, like trying to figure out what the color blue would sound like. This is the time when I really try to forget about any other musical responsibilities I have and just let my heart go where it wants to go while trying to keep my brain out of the way.

3. Things I’ve never done

This can sometimes overlap with the “things I want to do” category, but essentially, I try to do at least one thing per day that I’ve never done before. This part of my practice never really has a time limit and can be as simple as sight reading an étude . I just try to do something that gets me out of my comfort zone in hope that, eventually, it will feel more like home.

As far as rituals go, I can’t even look at my trumpet until I’ve had a shower and a cup of coffee. I’m a bit OCD about cleanliness, and this totally translates over to my practicing. If I feel dirty, what’s coming out of the horn is going to sound that way. I love to shower and let the water run on my lips for a while. It’s weird, I know, but it feels good and starts to get the blood flowing my lips, which is sort of the first step of my warmup.

Once I’m showered, I head to my favorite coffee shop near my house, (shout out to Meave’s in Northeast Minneapolis) and grab breakfast and coffee. This is my time to relax and think about the day ahead. I try to sort of paint a mental picture or lay out a storyboard in my head of how I want the day to go. This time might actually be more important to me than the actual, physical warmup.

Life, honestly, is my biggest distraction when it comes to practice. The world we live in today is full of amazing technological wonders and convenience. Everyone is used to always having something to do, having things happen quickly with relative ease, and constantly being in touch with other humans. It’s almost as if spending time disconnected from society is feared.

All of this stacks up pretty hard against a profession that requires you to spend hours alone looking in a mirror and thinking about every minute detail of an often ethereal concept. Generally, I’d rather be drinking a beer and playing video games.

For me, the best way to overcome not wanting to play music has been listening to music. Whenever I get in one of those moods where I’m unfocused, or on my phone or computer, and just not feeling motivated to practice, I try to force myself to listen to something. It really doesn’t even matter what it is, because as soon as I hear a recording of anything, I’m reminded that these artists made the choice to create something and put it out into the world because they believe that’s their purpose. Music is my purpose, not video games or Facebook. Sometimes it just takes a little reminder.

My biggest breakthrough in the practice room has been to solve a problem by working on both sides of it. I had an amazing teacher in college, the late Laurie Frink, who showed me that instead of always trying to work directly on one thing and failing over and over, you can create exercises that incorporate the thing you’re struggling with but don’t only use that thing.

Working on problems like this often helps me get through something much faster because I’m surrounding something I’m not good at yet with things that I am, so that positive-reinforcement mentally seems to make anything problematic infinitely more accessible.

My PPP

Find your limits and destroy them. Let mistakes lead to growth, and become more yourself today than you were yesterday.

+ Learn more on Soundfly: Learn to write for a string quartet with our popular Mainstage course, Orchestration for Strings, and receive personal feedback and live workshops with composers and orchestration experts!

Anthony Ware (Saxophone, Flute)

Anthony has performed in bands with Dee Dee Bridgewater, Theo Crocker, and Winard Harper.

While out on the road, I try to get at least my maintenance routine done on a daily basis. If I just do the bare bones, I can do a 20-minute warmup on flute and about 40 minutes on saxophone. If I have time, I’ll spend at least 30 minutes on flute and 90 minutes to two hours on saxophone. I try to average two hours a day at least.

On flute, I’ve been working on the Telemann Fantasias, F# minor in particular. I also take a few heads through a few keys to play through the full range of the instrument. On saxophone, I work through some standard Jackie McLean exercises, taking scales and other figures up and down chromatically across the horn. I do this at varying speeds in order to have complete control of the exercise. Different tempos require the use of different muscles. If you only practice fast, your medium-tempo muscles won’t be worked out.

Then, I focus on other random finger exercises. I try to focus on passages from music that I actually play that are difficult for me to play. I’ll turn small phrases into exercises in order to master difficult fingerings.

Lately, once I’ve completed these, I’ve been choosing a different key to work through every day. I’ll take some études and transpose them to the key of the day. Also, I work through heads and songs that highlight different types of harmonic motion. And I make time to work on songs that I have to perform or are on a list I’d like to learn.

I usually practice quietly in my hotel room. If time doesn’t permit, I’ll do my warmup routine onstage before, during, and after soundcheck. No rituals, but I’m always focusing on breathing and embouchure when I don’t have my instruments at my lips. I do start my practice routines with the flute which helps with my air flow and breathing.

A big thing in my development has been checking out saxophonists with things I feel I need to develop and trying to take the pieces I need and applying them. Bunky Green, Eric Dolphy, Dexter Gordon, and Jackie McLean have all been very influential on my playing.

My biggest obstacle is time. To overcome it, I have tried to figure out the most efficient exercises and ways of breaking things to their most fundamental parts.

My biggest breakthroughs have to do with saxophone and music. One day, I locked myself in a practice room for three hours in the dark with just my saxophone mouthpiece. I learned how to growl and do a number of other extended techniques that day, and I finally felt that I had control of the instrument.

For a long time, I only listened to straight-ahead jazz and gospel. I remember when that changed for me. I was at a jam session, and this guy played what might be characterized as a “smooth jazz” lick over “All the Things You Are.” The way he played it was so perfect that it made me realize that music was music and that there was no need to characterize or divide my taste based on genre.

My PPP

My philosophy is to realize I’m terrible and work to get a little better every day.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Rudy Van Gelder-The Optometrist Who Pioneered an Ethos in Record-Making”

Got practice tips of your own? Post them in the comments and it could inspire us to write an article about your PPP!