+ Soundfly’s Intro to Scoring for Film & TV is a full-throttle plunge into the compositional practices and techniques used throughout the industry, and your guide for breaking into it. Preview for free today!

Standard music notation isn’t quite as standard as it once was. For many types of music, it’s simply no longer the most efficient means of learning and recalling material.

Sometimes though, you can’t get around it. Horn and string players, if you hire them, typically like (or even need) dots-on-staves notation. Large ensemble writing of any kind almost always requires charts. Once in awhile, a song will need a very specific piano accompaniment, or your top-flight guest soloist will expect a chart.

In these situations and others, standard notation is still the best (and often only) tool for the job, so don’t let it rust in the corner of the shed. Keep it sharpened!

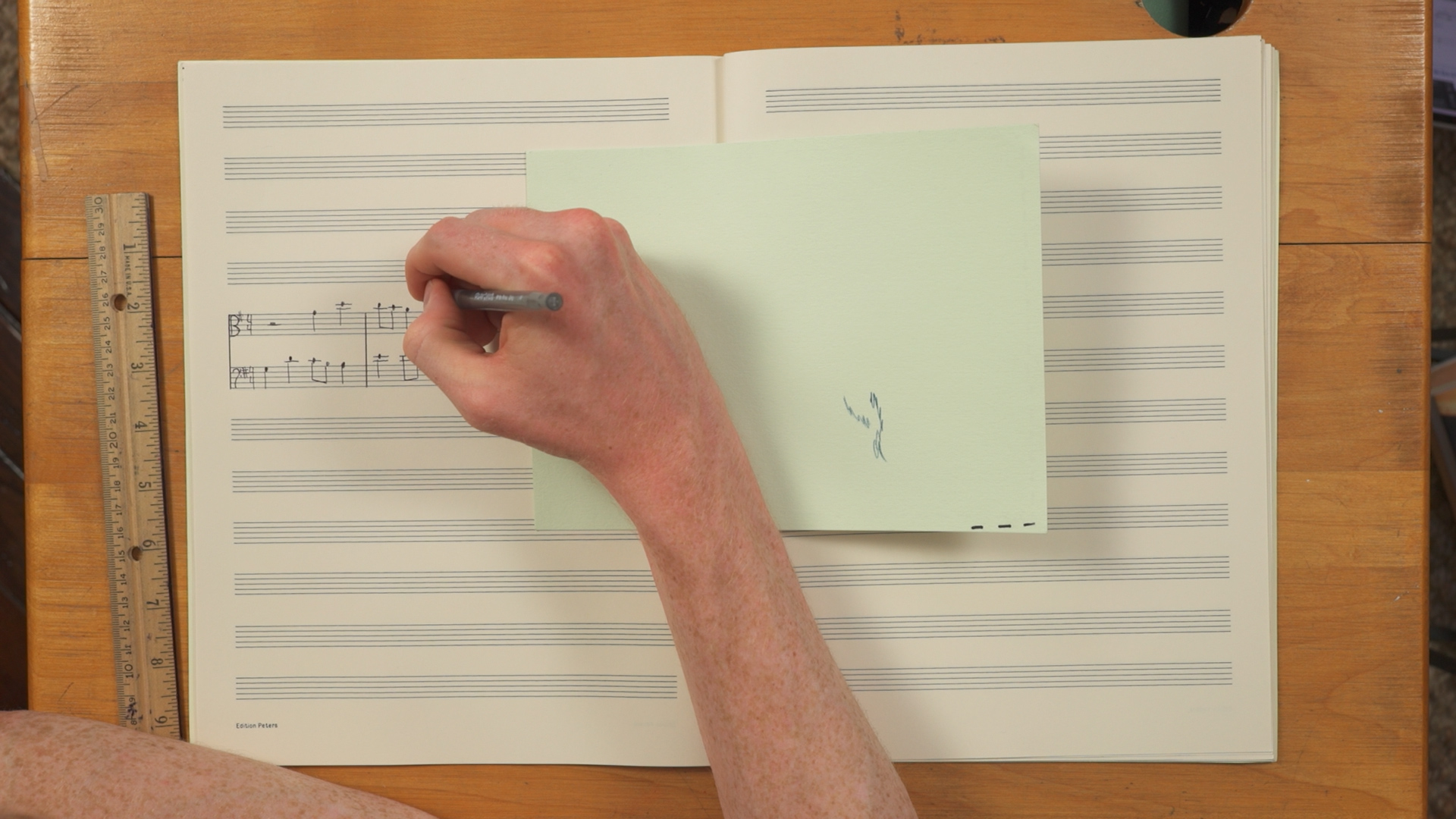

Whether you’re using a pen and onionskin paper or a mouse and MIDI keyboard, a truly legible chart requires a musical mind to craft each measure with foresight and design the overall layout with intent. Let’s start with a near-universal truth: every hour spent perfecting charts saves two hours of rehearsal time.

This is no exaggeration. (In fact, it may even be an understatement!) For starters, it’s important to not think of notation software like Finale or Sibelius as a time-saving tool. If you get really good at using it, sometimes the software will save a little time relative to writing music out by hand. Relying on its defaults, however, can be dangerous.

Things like page layout and music spelling can’t be reliably automated. These tasks require time and attention, and are not jobs you want to leave to a computer program any more than you’d want a computer program to write lyrics for you.

Once you’ve entered all of the notes, you’re barely halfway done. You still have to proofread, give the musicians other information they need to succeed, and format the overall layout. This is make-or-break stuff, so let’s go through it task by task.

Proofreading

It might seem odd to begin with proofreading, but when it comes to music notation, this isn’t a discrete, final process.

Proofreading is a continuous attitude. Particularly when working with notation software, constant vigilance is needed throughout the writing process to make sure the program’s defaults aren’t sabotaging your readability in a thousand tiny ways.

Stay vigilant throughout making your chart, and do a good, final read-through when you’re done. It’s important to make sure you finesse all linked and extracted parts individually.

Each part is its own work of art, so proofread accordingly. Examine each part after it’s printed, too, and keep a recycling bin nearby. Things our eyes gloss right over on a computer screen will suddenly become apparent once the ink hits the paper. We tend to think we’re immune to this, and we’re always wrong!

Double-Check for Errors

It’s not just that the software won’t always protect you from yourself. Sometimes it’s just downright buggy. It’s not as rare as you’d think to have accidentals or other items display improperly (or not at all).

It’s possible to end up with the wrong number of beats in a measure, or even to have a glitch or error cause some bars to go missing without warning.

Be vigilant. Carefully avoid collisions (see below) or areas where multiple elements of the chart touch or overlay one another. This reflects carelessness and is easily avoidable.

+ Learn more on Soundfly: You’ve always wanted to learn to write for a string section. We can help with that! Explore our month-long intensive course, Orchestration for Strings.

Spelling and Rhythm

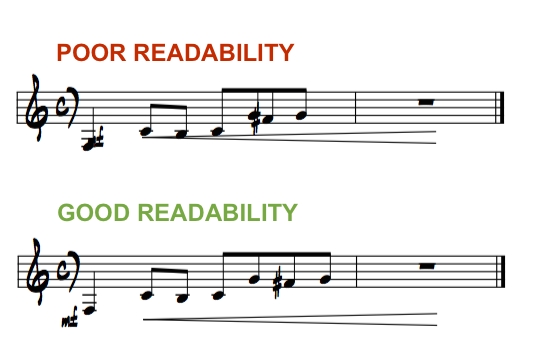

It’s not enough to enter notes, listen to playback, and let the computer decide how to spell your music, because the default spelling may be enharmonically confusing. Players expect anything bizarre looking to be bizarre sounding, and it’s our job to manage those expectations.

Music that appears odd on the page but sounds simple when played creates cognitive dissonance, which leads to players second-guessing and losing concentration.

In the example below, I’ve substituted a B-natural for the C♭ on beat one and avoided having both a G♭ and F# in the same measure.

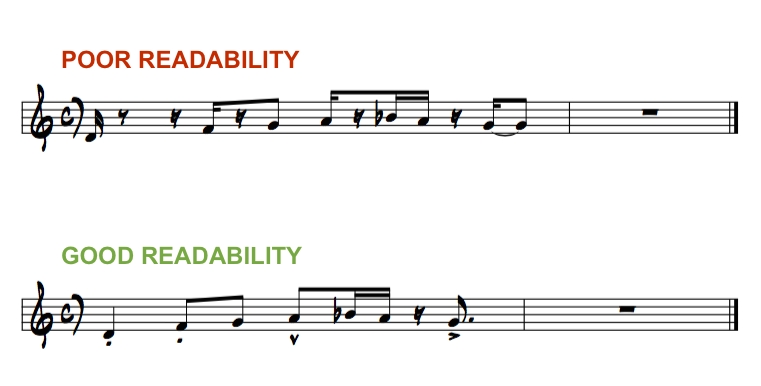

Expectations management extends to rhythmic figures, too. Both systems in the example below would sound more or less the same on MIDI playback, but notice how much more difficult the top system appears! At first glance, the note on beat two looks as though it might be syncopated, creating confusion and uncertainty. In the bottom system, note the use of articulation markings (in lieu of rests) to help specify shorter note durations.

Know Your Range

A common (and embarrassing) error is writing notes that don’t exist on the instrument. Check the scoring or vocal range and understand that many instruments get dynamically less flexible and generally less reliable at either extreme.

Anything that looks funny — lots of ledger lines above or below — should be a red flag. Make sure you understand what’s possible, what’s practical, and what’s musical on the specific instrument for which you’re writing. When writing for unfamiliar instruments, it’s wise to stay away from extremes until you gain more experience. (Double-check that you’re in the proper clef and transposition while you’re at it!)

+ Read more on Flypaper: “The Weird and Creepy World of String Harmonics”

Go Beyond the Notes

Dots on a page aren’t music. They’re instructions for making music. It’s in the interest of good performances, time, and money to make those instructions as comprehensive as possible. The devil, as usual, is in the details.

Articulations and Cutoffs

The rhythms you write tell your player when the notes should begin, but most of the information about when the notes should end is conveyed through articulations and cutoffs. Careful use of these markings will make your group play tighter sooner.

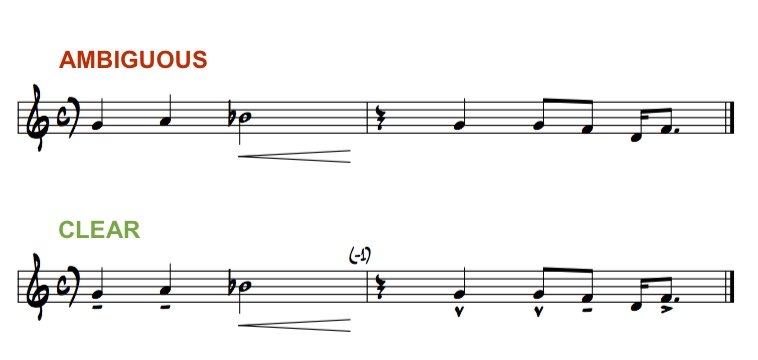

For longer values that should end crisply, specifying a cutoff removes some of the players’ guesswork. In the bottom system of the example below, the half note in the first measure is specified with a “(-1)” to cut off on beat one of the following measure.

The composer’s intent for streams of very short notes is often clear enough, but vagueness is often a problem on intermediate values. If you show four musicians a naked medium-tempo quarter note, it’s almost certain that each one will articulate it differently.

For this reason, it’s wise to supply more information in the form of an articulation marking. The better the section, the more they’ll match the interpretation of the lead player, but it’s risky to leave this to chance. If the lead player wishes to change the articulation, he or she can discuss with the section and modify with pencil.

It is possible to go overboard. Running streams of sixteenths with articulations on every single note may cause visual clutter and compromise readability. But within reason, erring on the side of specificity leads to immediate ensemble tightness.

+ From the archive: “What is a Music Engraver? (And What Does It Take to Become One?)”

Dynamics

Don’t leave your players guessing about how loud they’re supposed to play. Write dynamic markings clearly and consistently.

Make sure to take into account that some instruments are dynamically limited in certain registers. (For example, don’t ask your trumpet player to play an E above the staff pianissimo.)

Guideposts

Good readers have strong concentration, but visual cues on a chart can go a long way toward preventing uncertainty and confused trainwrecks. A well-laid-out chart typically has a few of these cues, which I call guideposts, built in.

Repeat bars, D.S. signs, and rehearsal letters tend to naturally land at beginnings or ends of sections, making them helpful visual cues. But especially when these aren’t present, it’s helpful to call out section changes in other subtle ways.

A well-placed double barline between sections, for example, says so much. Its presence visually reinforces the sonic change that’s occurring at the transition point. Remember, a player who’s confident he or she is in the right place will give a stronger performance.

Such guideposts are particularly important during long stretches of repeated ostinati or unadorned “slash” notation. In these situations, many players appreciate a numeral in parentheses over the fourth, eighth, sixteenth measures, etc. This can help them avoid becoming adrift in a sea of identical-looking measures.

Text instructions are also good guideposts. In addition to a double bar, consider writing “bridge” or “chorus” near the first measure of a new section. Cues like “vocal in” or “strings enter” can be worth their weight in gold, too. Finally, clues to orchestration are useful. If a player is alone on a part, for example, specify ”solo” for a more confident entrance.

The best guidepost of all, however, is a well- and logically laid-out chart. Most notation software defaults to chaos where this is concerned, but there are several strategies you can use to impart some order.

Line Breaks are Guideposts, Too

Take care to organize measures in a way that reflects the music. If the tune consists of four- and eight-bar phrases, keeping four measures on a line allows your line breaks to double as visual form cues.

If there’s an odd five-bar phrase, put five measures on that line before going back to four on the next line. Treat first- and second-endings logically. Try to make double bars land at the end of lines, and D.S. signs land at the beginning of them. Don’t underestimate how powerful a logical layout is for keeping everyone in the right place!

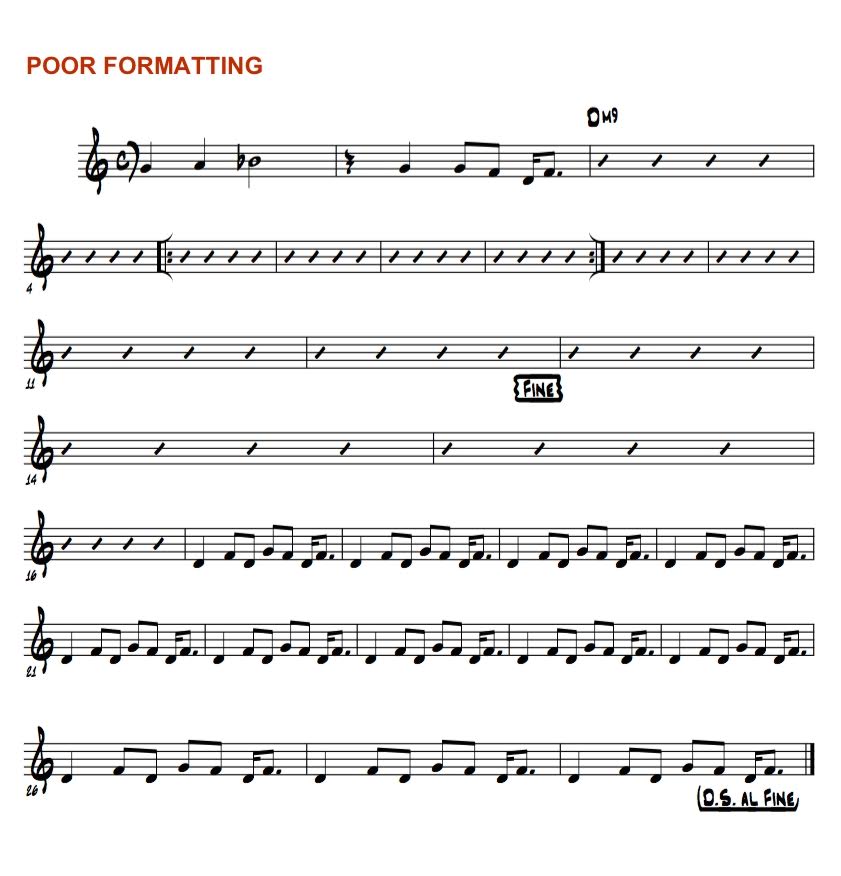

In the following example, notice how line breaks occur in unnatural, random places, and that there’s a senseless indent on the first line (a default of the notation software I use).

There are interminable measures of a single chord (followed by interminable measures of an ostinato) without a double barline in sight. Making matters worse, there aren’t many clues to what else is going on in the music. To say this chart puts the player at risk of getting lost is an understatement — it nearly ensures it!

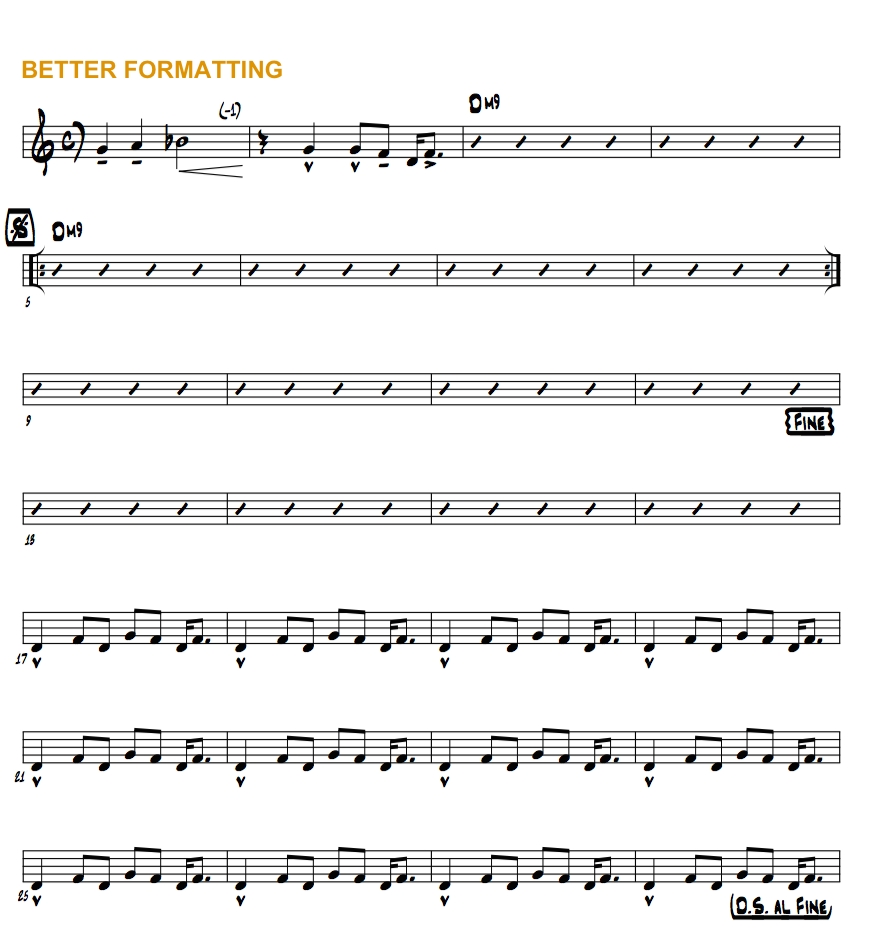

The following revision of the same chart is better. There are logical numbers of measures on each line. The repeat bars and jumps are now at beginnings and ends of lines, helping them serve their secondary function as natural guideposts.

This basic formatting took mere seconds, and made a drastic impact on the chart’s readability.

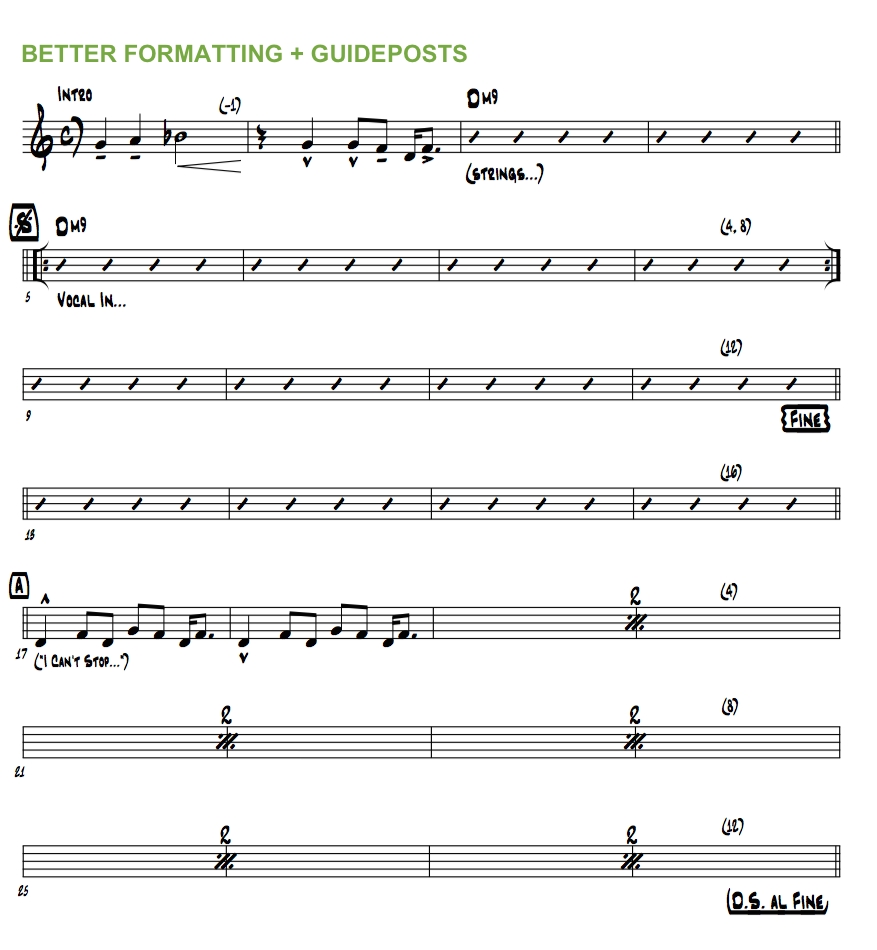

We’re still not done, though. If we add some helpful guideposts to our improved layout, our chances of a successful sightread increase even further. In the final revision below, note how the double barlines (and the rehearsal letter “A”) signal section changes.

Once the vocal enters, the parenthetical numbers allow the player to see at a glance that the long stretch of Dm9 lasts for 16 measures. Similarly, the two-bar repeats after letter “A” allow the player zoom out and focus on form, rather than zooming in on each measure as though it were brand new.

Finally, text that cues important entrances (like the lyrical cue at “A”) help reassure the player that they are in the right place (and alert them when they aren’t).

These additions did require a minor time investment, but remember our rule: every hour spent perfecting charts saves two hours of rehearsal time.

Save a Tree, but Don’t Cramp My Style

Two standard-size pages fit easily on an average music stand; three is workable if the part is taped. Four is pushing it, and any more than that becomes an encumbrance.

A player worried about shuffling pages is distracted and not performing his or her best. So, with that in mind, some space-saving tactics — like intelligent use of multi-measure rests — are easy and without disadvantage. But much about page layout is juggling a series of trade offs.

Carefully consider your margins, and whether squeezing your systems just a little bit closer together might save an annoying page turn without causing clutter. If you end up with a single system on a fourth page, find a way to squeeze it all onto three.

Repeat bars, endings, and jumps to D.S. signs and codas are slightly more dangerous than a chart that reads straight down. They save so much space (and are so customary), however, that they’re almost always worth the trade off.

Hopefully you can avoid annoying page-turns, but if one is necessary, make sure it occurs in a logical place. Adjusting your formatting so that a nice multi-measure rest occurs at the end of a page is a great solution.

No Points for Difficulty

Composing and arranging are beyond our scope, but let’s touch on one area where they dovetail with readability. Artful writing conveys complex concepts with simple syntax.

Don’t write “Bb6add9#11(no 3rd)” when “C/B♭” means the same thing. If you have an unusual chord in your piece, see if you can find a simpler name for it. If there isn’t one, consider the possibility that chord symbol notation is the wrong tool for the job.

Chord symbols are blunt instruments designed to communicate the broad, gestural thrust of the harmony. They’re useful when you wish to empower the player to improvise a creative accompaniment within a loose harmonic framework.

If you need to micromanage, that’s okay, but choose an appropriately precise tool. If the harmony needs to be structured in a very specific way, consider notating the exact voicing within the staff (as opposed to writing a sentence above it).

It goes without saying that simpler material reads more easily. Part of this is mental. If something looks easy on the page, the player will have greater confidence and is less likely to panic or get psyched out. If you can manage to make even difficult material appear simple, you’ll get the most out of your ensemble.

Why This Matters

Most players will do their best to make you look good, but you have to help them help you. If you set them up to succeed, you’ll look like a genius.

The opposite situation can, at worst, strain professional relationships. If you’ve inadvertently laid multiple traps in your charts that make players look foolish in front of their peers, they won’t be in the right frame of mind to give their best, and vibes can turn negative quickly.

A clean chart shows respect for your collaborators, their time, and their energy. It’s a testament to your professionalism. Perhaps more importantly, it demonstrates that you care about the music, and this will make the players care, too.

The raison d’être of written music is to communicate. If we do our job well, we can communicate most of what a player needs in order to effectively execute our musical vision. But whether we do our job well or not, a chart communicates more than a little about the person writing it. With a little careful attention and a few strategies, we can make sure we like what it says!

Have you checked out Soundfly’s courses yet?

Continue your learning with hundreds of lessons by boundary-pushing, independent artists like Kimbra, Ryan Lott & Ian Chang (of Son Lux), Jlin, Elijah Fox, Kiefer, Com Truise, The Pocket Queen, and RJD2. And don’t forget to try out our intro course on Scoring for Film & TV.