Welcome back to Soundfly’s weekly interview series, Incorrect Music, curated by guitarist, singer, and composer Lora-Faye Åshuvud (of the band Arthur Moon). In this series, we present intimate conversations with artists who are striving to push the boundaries of their process and craft.

Dre’s interview with Matt Mehlan (of the avant-garde pop band Skeletons) makes me smile wide and sad for New York’s lost DIY venues. The ethos is still here, though, lurking on newer, stickier stages and in the dark corners of practice spaces late at night. And it still lives strong in Mehlan’s music, even though the artist has since moved back to his hometown of Chicago.

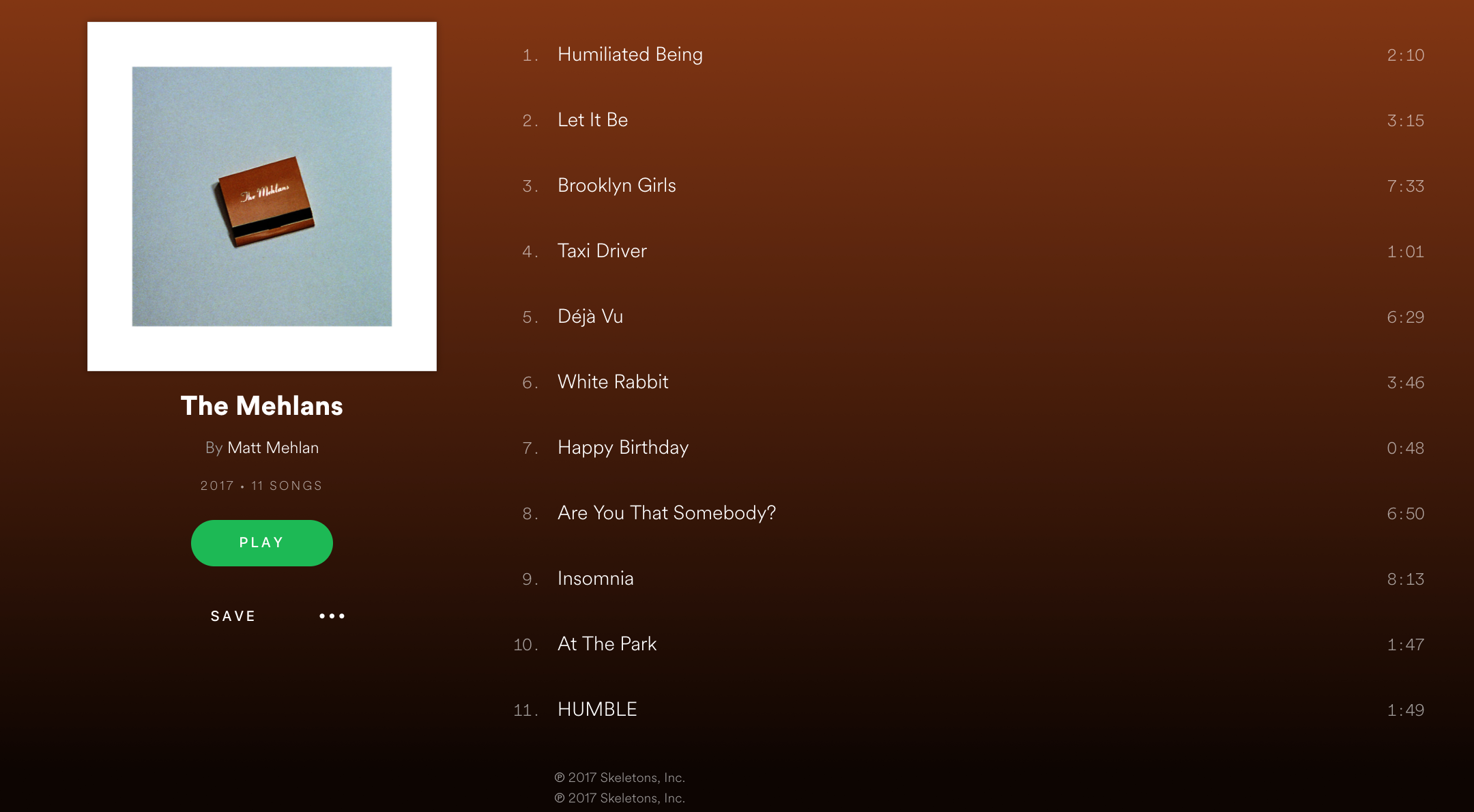

Dre, who describes Matt’s latest solo release, The Mehlans, as “lush waves of electronic architecture and warm guitars” asked Mehlan what he thought of our “incorrect music” idea, and Mehlan gave this lovely response about his own attention towards imperfection in recording: “There is always some sloppiness, which I tend to like and will let come to the forefront if the feel is right.”

Matt Mehlan’s new album, The Mehlans, is out now via Shinkoyo Records.

– Lora-Faye Åshuvud

Interview by Dre DiMura

I listened to your record before reading any of the press materials, and by the third or fourth song, I guessed you were either from, or had lived in, New York. I used to see a lot of shows at spaces like Death By Audio and 285 Kent, I know you were a big part of that scene. How did that experience change you as a musician and influence the songs on the new record?

I learned how to be an adult person in New York. I turned 21 there, had my first real job there, understood myself through the city. It’s the kind of place to do that. My wife and I moved there on an impulse to escape Chicago winter and our post-college suburban mall jobs, and we did the thing: arrived with no money, worked hard, wiggled our way into a life there, had a baby there — and it was amazing and hard sometimes. [There are] so many friends and important people there… and such a great and intense energy.

What’s called “the DIY Scene” was a huge part of my life. 285 Kent before it was “285 Kent” was where my friends lived and made music and art; they called it Paris London West Nile. Silent Barn was our house before it was “Silent Barn” — which we sought out because there was no way we could afford both a place to live and a place to make music.

And so other places like those places, were the places we wanted to play shows: DBA, Less Artists More Condos, Shea Stadium. Shows being put on by people who were enthusiastic enough to say fuck it and make something happen, an actual alternative. It was edifying in every way.

The first artist that came to mind as I was listening was Dirty Projectors. How much inspiration are you drawing from your contemporaries versus older material that you grew up with?

They are the best, surely, in all incarnations — and all the things they’ve [done] individually, too. Nat’s music, Angel’s music; all great. We were lucky to inhabit the same spaces for a bit, do some touring supporting them just before Bitte Orca came out, watch them hone their insane abilities into the kind of mastery onstage that you rarely see.

There was a moment for me in New York where there was a really great energy of a kind of competition between bands that weren’t even likely sharing much common audience. It might’ve even just’ve been in my head, but it was super inspiring and pushed me and us (Skeletons) to do new things, be even more ambitious.

To kind of semi-answer your question, I miss that kind of close-proximity “local” competitive energy, as I’m a bit separated from it now, but maybe we all are a bit atomized in our Internet Vibes™.

And, I also heard elements that reminded me of first generation prog acts like YES and King Crimson. For example, the guitar riff at 2:42 on “White Rabbit” conjures memories of “South Side of the Sky” and The Yes Album for me. Are you directly influenced by those artists or are your influences several generations removed?

Man, for sure — Fragile and Close to the Edge are two of my favorite records. I’ve never been one to sing about goblins, but musically, as well as the sound of those recordings, are definitely influential. I’ve always been attracted to that era of music-making, in particular some of the music that was really maligned by the ’90s autodidactic punk perspective.

I don’t believe that things are so simply cyclical, but it’s easy to see how the generation before me was so over “the excess” of ’70s and ’80s rock music, and how, especially as a music-school kid, that uncool music was really appealing to some (like prog, fusion, etc.). In general, I am drawn to music that is polarizing — even more so if there is a popular consensus that something is bad, it just makes me more curious.

“I think place exerts an extreme influence on the music that gets made within it.”

The way you play with time on the record is really exciting, especially on a track like “Brooklyn Girls.” On “Deja Vu,” you have this great 6/8 groove but with the accents coming at the end of the measure. A lot of musicians stick with some very familiar feels and time signatures. I know you went to Oberlin and studied music there, but where does that exploration and fluidity come from?

The feel is the most important part of a song for me. I’ve been hugely inspired by the African musicians I’ve performed and made music with (Congotronics Vs Rockers with Konono No. 1 and Kasai Allstars, and Janka Nabay) where feels are mostly in three and the hierarchical priority to the one (the downbeat) is not given.

Going back even earlier, I just had a natural inclination towards compound meter, or polyrhythms, or the kind of meter (I’m spacing at the music phrase at the moment) where within the measure you have pairs of twos and threes. People mention to me sometimes that so many of my songs are in three, but really, they’re all also in two or four!

I’m obsessed with this kind of feel, for example, one of my favorite songs ever:

So with my Western Music School brain and the brains of other musicians I’m getting to play with, sometimes the search for the ways this or a similar kind of feel can be achieved is by pushing and pulling the actual meter, swinging and then not swinging, trying to do both simultaneously.

You obviously borrowed some song titles from other artists, like Kendrick Lamar, Jefferson Airplane, and the Beatles. which I think is great. Can you reveal your intention there?

I mostly tried to think of titles that already existed as titles, which most closely related to the actual content of the songs. I started borrowing phrases here and there a few records back, sticking little references in… which I’m doing on this record, too. We [Skeletons] did a single called “Welcome to New York / Brooklyn Girls,” where the idea was to do a cover version of those songs without actually doing a cover version at all. Jason (from Skeletons) and I started joking about a new record being called What’s Going On or Thriller and so on.

We mostly live in a media space where these kinds of words and phrases already contain some meaning and relation and value — which seemed useful to me. We also mostly listen to music in this algorithmic search and recommendation universe built from a metadata of the English language. It seemed strategically minded to start engaging that in a way that might benefit me.

Obviously, nowadays, it isn’t uncommon for an artists to sort of “construct” a record from their home. You played every instrument on the record. Has that always been the case? And how did that change your approach to writing and recording?

It’s really (actually) the way I started making my own music — multi-tracking myself on a four-track. All of the members of my band in junior high (we played “Verse Chorus Verse” by Nirvana in the school talent show) all quit the band the summer before freshman year of high school, individually, and then secretly started a new band together with the guy who had a mohawk at school. It was kind of devastating at the time, but it put me in a solitary space where I focused on recording and really learned how to make songs.

This record felt kind of similar to that, partially because I’m back in that same house, but also because the real band I always wanted, that Skeletons came to be, had kind of fully dispersed in a similar way. I don’t think it’s because there’s a guy with a mohawk somewhere they’d rather be in a band with, but I dunno. I feel totally comfortable working this way. I just also find it kind of isolating and am constantly in awe of other musicians. And I would rather see what they could bring to an idea I have than pile my own ideas on.

The tracks are pretty dense sonically. How do you plan to recreate these recordings live?

I’ve put together a band here in Chicago. We’ve been completely slaying, doing a residency every Thursday this month at a place called The Comfort Station. The band features Phillip Sudderberg (Grandkids, Wei Zhongle, Ken Vandermark’s Marker) and Ryan Packard (Nestle, Fonema Consort, Gunwale) who toured with Skeletons last year; Ayanna Woods (composer and singer-songwriter, a.k.a, Yadda Yadda); and Charlie Kirchen (Rooms Trio, The Few). That makes two drummers and two bassists — plus my longtime friend and collaborator Jeremy Keller (Baby & Hide). That’s how we do it.

Do you have a studio secret weapon? Something that you feel is crucial to your sound? Or a piece of gear that really sparks your creative process?

I’ve learned, perhaps conditioned by the American Love of Shopping, that I like to be in a constant process of buying and selling equipment. A new instrument or tool brings me ideas and excitement, even if fleeting, that is important to keep on making new things. I also have instruments that I’ll never get rid of: my Rhodes piano, guitar, my saxophone.

One of my favorite lines on The Mehlans is, “Love is a homework assignment.” What’s influencing you lyrically? Are you a music- or text-first songwriter?

I don’t know anymore what kind of text person I am anymore. I used to walk around with song lines in my head everywhere I went, basically keeping a running log of phrases I liked the sound of, feelings I wanted. Now I have to set time aside for writing.

I read more than ever now. I went to grad school a few years ago, which re-upped my reading practice when I’m not drawn to my phone’s demands to keep shopping.

At Soundfly, we love to use the term “Incorrect Music” to describe the things an artist does that go against the status quo, or even their own instincts, but which yield exciting results. What about your music might you consider to be “incorrect”?

I’m averse to perfection. Actually, let me rephrase that — I think perfection is false. I don’t see the point in chasing it. I’d rather spend my finite time alive working on a new idea. That means there is always some sloppiness, which I tend to like and will let come to the forefront if the feel is right. It’s also a source of some self-doubt, but I think that’s normal.

I watched the documentary you feature in about the closing of 285 Kent. Something you said about other people, especially on the internet, not getting it, not understanding why it mattered and what it means now that it’s gone really struck me. I remember feeling the same way about those places and bands, asking myself, “Will people remember this? Will they write about it 30 years from now?” Do you think the Brooklyn DIY scene left enough of a mark that it will feature prominently in the annals of music history?

It’s really a question of political and media power. I do think it was important to the people who experienced it. Those people will go on to do things elsewhere in New York and around the world, and hopefully, the things they do, and the kinds of visceral and foundational experiences they had, like I did, in that scene, will have a positive impact.

You relocated back to your native Chicago with your family prior to recording The Mehlans. Is there a specific moment or track on the record that you feel was inspired by that experience?

Ah, the whole thing. In a way, I’m slightly embarrassed at the warm domestic quality of the record, which is in part why I decided to call it The Mehlans. Like I said earlier, I really came to define myself through the city I lived in, New York, and so the move back to Chicago was difficult at times to come to terms with. At the same time, I love it, it’s familiar in another way, it’s where I grew up — I learned to be an adult in New York but I learned to be a human in Chicago — and this is the kind of music I probably never would’ve found the time, or space, to make in New York.

I think place exerts an extreme influence on the music that gets made within it.

Lastly, is that penny whistle I hear on “Humiliated Being”?

Nope!

Looking to advance your skills and open up more opportunities in music? Explore Soundfly’s growing array of Mainstage courses that feature personal support and mentorship from experienced professionals in the field, such as Faders Up: Modern Mixing Techniques, Beat Making in Ableton Live, Orchestration for Strings, and Unlocking the Emotional Power of Chords.

Sign up for our On The Fly newsletter to receive exclusive discounts on current and forthcoming courses!