+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

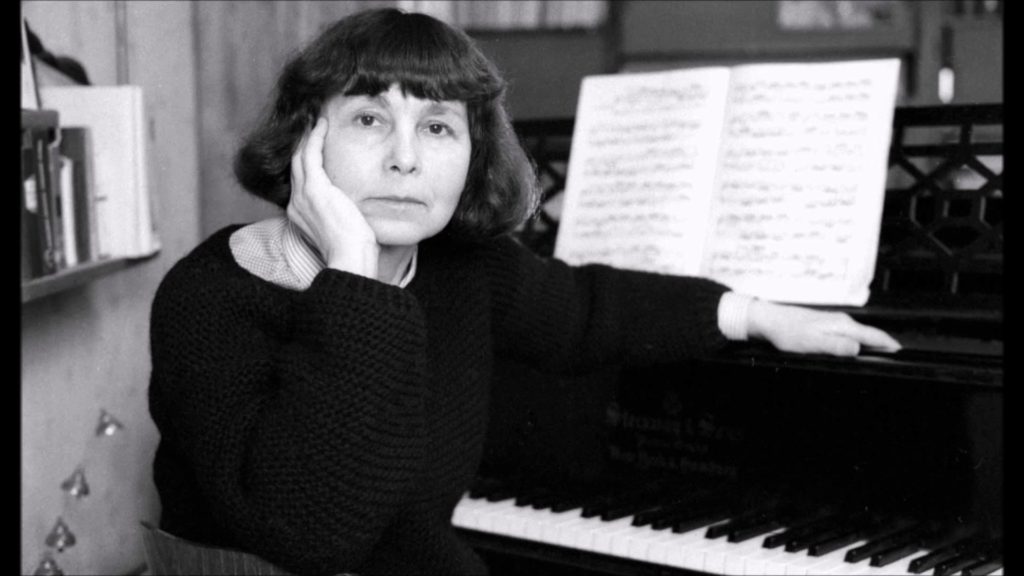

If you wander up an unremarkable remote backroad outside a certain quiet village in Germany, you might stumble across the home of one of the world’s most venerated living composers, Sofia Gubaidulina. She’s 86, and still working hard. I mean, realistically, you won’t bump into her. There are loads of unremarkable remote backroads leading in and out of quiet villages all over Germany. Gubaidulina lives on one such road, which she chose specifically by virtue of its unremarkability and remoteness.

Yet she’s absolutely not the grumpy, reclusive artist archetype who just wants to be left alone — she fields commissions from ensembles all over the globe, and regularly grants interviews with grace and humility. It’s just that Gubaidulina has always been a composer who values silence as a tool for creating her quite remarkable work, perhaps now more than any other time in her life. In her own words, “I am old, and it is harder to write than ever.”

Considering the details of her life’s story and artistic development, that’s saying something.

Born in 1931, Gubaidulina spent her formative years in the Soviet Union during Stalin’s reign. As you can imagine, growing up under the shadow of a brutal, murderous dictator often tends to pour cold water on one’s personal artistic expression. Aside from having to learn to deal with the general paranoia and inconvenience of living in a society in which neighbors spied on neighbors and familiar persons mysteriously “disappearing” on a regular basis, Gubaidulina had the added pressure that music, like all art in the Soviet Union, was intensely regulated by the government.

Anything deemed “too experimental” (as vague a parameter then as it is now) was seen as being extravagantly bourgeois by the State, and the composer responsible risked punishments ranging from widespread state-sponsored derision of their work, to being blacklisted from performance or government support (career death for those in a communist society), or, even worse, being given a one-way ticket to a gulag in Siberia.

Despite this, Gubaidulina demonstrated an unsquishable curiosity for music composition throughout her childhood, experimenting with tunings and timbres until she arrived at the Moscow Conservatory in her 20s. One of her mentors there was a man who knew all too well about the violently capricious whims of the ruling Communist party: Dmitri Shostakovich.

Shostakovich’s tumultuously hot-and-cold relationship with Stalin is legendary, and if anyone knew firsthand the dangers of pissing off the powers-that-be, it was him. Meanwhile, the young Gubaidulina had developed a reputation for pushing the boundaries of what was artistically acceptable, and had been warned that her artistic impulses were “mistaken,” which was a beige 1950s Russian euphemism for “eventually going to get you killed.” Yet when appraising her work during her final examination, Shostakovich strongly encouraged her to “continue on your own incorrect path.”

Gubaidulina later recalled, “I am grateful my whole life for those wonderful words. They fortified me and were exactly what a young composer needs to hear from an older one.”

Gubaidulina’s “incorrect” path was twisty. She immersed herself in a myriad of avant-garde composition trends and experimented with sounds and ideas of her own. Stalin’s death in 1953 initiated a gradual loosening of the screws of ideology within Russia’s artistic overlords. However, although now artists did not necessarily risk actual, literal death when they made something a bit left of center, artistic expression was still strictly monitored, and Gubaidulina’s devoted experimentation drew increasingly hostile attention from exactly the kind of people you don’t want to annoy in a dictatorship. This, coupled with the fact that her music was managing to get past the iron curtain and into the ears of receptive Western audiences without the say-so of the establishment, led to her being blacklisted in the 1970s.

For most Soviet artists, this would have meant having to flee the Soviet Union, or else simply finding a new career. But for Gubaidulina, it meant freedom. Building upon her microtonal experimentations, she began to explore improvisation and Russian folk music using traditional instruments, and her religion and spirituality began to manifest itself more and more explicitly in her work (Gubaidulina is a devout Russian Orthodox Christian).

Perhaps because they couldn’t squash her themselves, the KGB finally decided they’d had enough of her. In 1973, an attempt was made on her life by a hitman who tried to strangle her in her apartment building’s lift. But even in the face of secret state-sanctioned death, Gubaidulina was confidently unflappable. “Why so slow?” she challenged him, as though he was taking too long and she had things to do. Maybe he was creeped out by her utter refusal to be afraid of him, or maybe she hurt his feelings with her brutal criticism of his abilities. Either way, he fled. Gubaidulina went back to composing awesomely unique music.

Finally, in the late 1980s, Gubaidulina’s international reputation outgrew her oppressors’ ability to keep her under their thumb. She had composed a violin concerto called Offertorium for the Latvian virtuoso Gidon Kremer, who had been traveling freely around the West for decades, and was championing her music to anyone who would listen. Thus, her reputation exploded around the same time that the Soviet Union imploded (which has a pleasantly narrative symmetry, if you think about it).

But what might seem odd from the outside is that, despite enduring a lifetime of fickle artistic oppression under the Soviet regime, it wasn’t until the USSR collapsed that Gubaidulina moved to her little house on an unremarkable remote road outside a little village in Germany. Like most things in her life, Gubaidulina did it because she wanted to. Not because she had to.

Gubaidulina’s work, as well as her life, is truly unique. She gets compared to Estonian composer Arvo Pärt a lot. But aside from both having overt religious associations in their music, and perhaps being inspired by the brutal North European cold, the two really aren’t that similar. Gubaidulina’s work is a result of a lifetime of experimenting with alternate tunings and microtones, or literally the sound of two very slight dissonances rubbing up against each other. Structurally, her work is built around numerology and mathematics, most famously the Fibonacci series and the Golden Ratio. But there is a lot going on in there, and any serious student of composition would do well to pick one of her pieces apart to see how it all fits together.

However, perhaps the most important thing to know about Gubaidulina’s work is that she sees it as bringing her closer to God — like Pärt, and Coltrane, and Santana, and so many other incredible musical thinkers.

“True art for me is always religious; it will always involve collaborating with God.”

The challenge now is to pick out some of her works that exemplify the voice of a woman who’s been composing since before McCarthyism was cool. Here are five of my personal favorites; please share yours in the comments if you’d like! And if you’re interested to learn more about composing yourself, I teach Soundfly’s Mainstage course, Introduction to the Composer’s Craft.

Offertorium (1980)

The violin concerto composed for violinist Gidon Kremer that really grabbed the attention of Western audiences, as a result of Kremer touring it around the world and introducing new audiences to her music.

String Quartet No. 4 (1993), a triple quartet for quartet, two taped quartets and ad libitum colored lights

Performed by, and dedicated to, none other than the Kronos Quartet, this features a pre-recorded “tape” made of a separate string quartet tuned a quarter tone out from the live quartet, as well as ping pong balls bouncing on strings. It’s also creepy as hell, so don’t listen to it in the dark (or do, if you’re a masochist).

Fachwerk (2009), concerto for bayan, percussion, and string orchestra

A bayan is a Russian folk instrument similar to an accordion, and it has a starring role in this insane piece of music. Tone clusters? You’ve never heard a tone cluster until you’ve heard it played on a bayan and a dozen low strings at once.

Revue Music for Symphony Orchestra and Jazz Band (1976), aka, “Concerto for Two Orchestras”

This one’s name gives off a false impression of boredom — it’s like a plain door disguising a pumping speakeasy.

Perceptions (1981), for soprano, baritone, and seven string instruments

Gubaidulina has complicated feelings toward rhythm and tempo. She often organizes pieces without “rhythm” so much as temporal clusters generated by numerical sequences like the Fibonacci Sequence, whereby each numerical subset is equal to the sum of the two subsets that came before it. Parts of this piece feature quarter-note cells proportionally divided out into lengths derived from the Fibonacci Sequence.

Tim Hansen is the instructor of Soundfly’s Mainstage course, Introduction to the Composer’s Craft.

Want to get all of Soundfly’s premium online courses for a low monthly cost?

Subscribe to get unlimited access to all of our course content, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.