+ This week on Flypaper, we’re exclusively featuring content that covers music initiatives and recordings from prison, in our editorial series, Behind the Bars: A Week Dedicated to Music In, About, and From Prisons. Follow along via this tag or sign up for Soundfly’s mailing list to stay informed about all of our online learning programs.

As recent events have forced us all to reexamine racial equality in the United States and beyond, the music community has also turned inward to recognize and reaffirm the essential contributions Black artists and musicians have made on our lives and culture.

As a major devotee of the British Blues Boom myself, I was always acutely aware of the impact Black progenitors had on the music I have known and loved all my life. I’ve been grateful for the opportunity lately, amidst all this growth and turbulence, to double down on my commitment to illuminate and honor the traditions and contributions that continue to shape music, culture, and the very foundations of how we interact with one another.

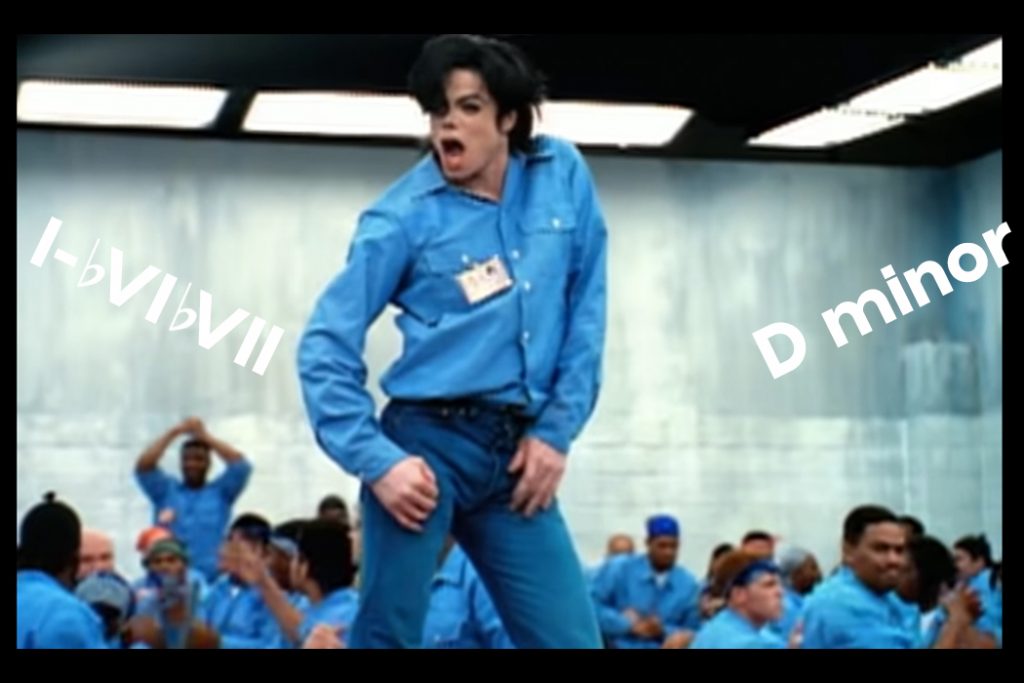

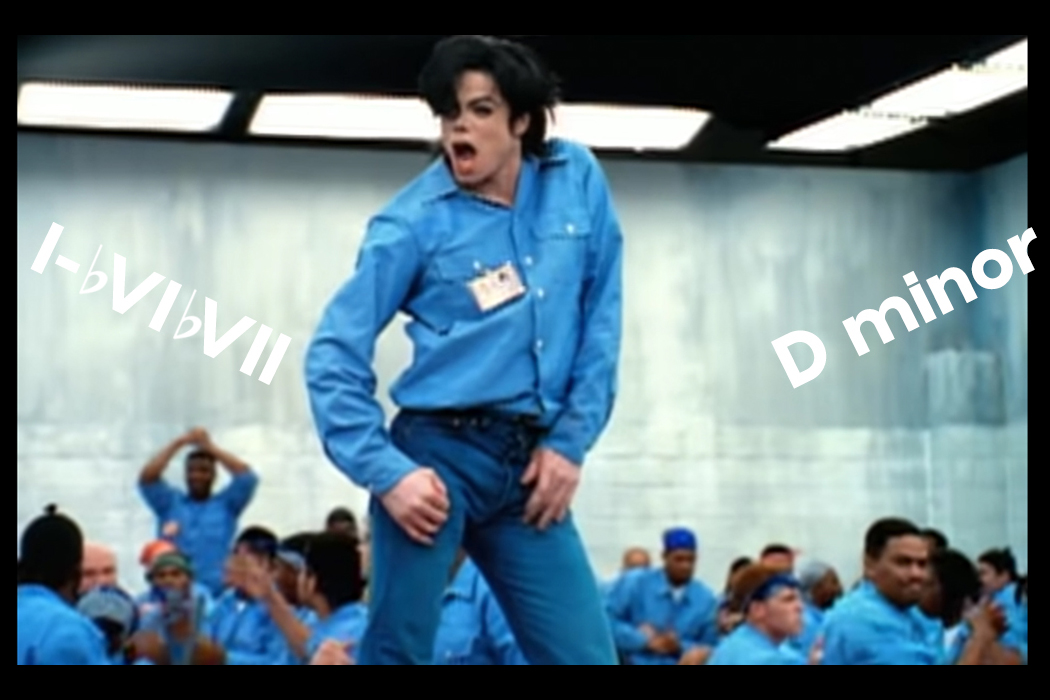

So, I wanted to turn back the clocks and shed light on a musical work that reflected a similar period of racial tension and unrest in America to what we’re feeling today. In 1995 — following a half decade of racial tension in the U.S. from the Los Angeles Riots of 1992 through to the OJ Simpson trials, and a growing awareness of the problems with our country’s prison-industrial complex — the King of Pop, Michael Jackson released his most controversial, and often overlooked protest song, “They Don’t Care About Us.”

The above is the second of two music videos created for the song, both were directed by Spike Lee, but this one focuses solely on depicting and aligning Jackson with U.S. prison inmates.

The song also received a ton of critical controversy upon its release over its lyrical content, despite Jackson’s pleas that he was attempting to align himself with the victims of racial abuse. However, since the Black Lives Matter movement has gained momentum and widespread support recently, this song has been reappropriated as an anthem of unity and solidarity.

A brief but important note just to mention that, as it needs to be mentioned, we here at Soundfly do not condone or excuse the alleged behavior of the late Michael Jackson with regards to his history of sexual abuse and assault. We’re saddened and angered to have learned about this in recent years and it does absolutely bear on our ability to enjoy and publicize his music; Jackson has caused great pain to a great many people who have experienced sexual abuse personally, and it’s for this reason we generally hold back commissioning new content that explores his catalog. The reasons we chose to analyze this song from a purely musical standpoint are twofold. Firstly, we do find some objective positivity in the fact that at the height of Jackson’s global popularity, he chose to use his platform to shed light on domestic prison reform and equality issues in his music and video, and that’s worth reflecting upon for a moment. And secondly, compositionally there is a lot that songwriters and producers can learn from the musical techniques he employs (which you’ll read about below).

So today, I’d like to reexamine Jackson’s “They Don’t Care About Us” from a musical standpoint and analyze its construction harmonically.

Overview

“TDCAU” builds and evolves patiently. Its minimalist harmony and primal, percussive characteristics create a strong foundation for Jackson’s powerful vocal top-line writing.

The song is structured almost like a short-form classical piece of music, given the introduction and recapitulation of various ideas throughout (what is sometimes referred to as “theme and variation”). A unique facet of this song is that it contains two different verse melodies, and alternates between them throughout the song. Some talking points are the subtle use of modal interchange, a motoric ostinato, inversions, and the influence of Jamaican Dancehall.

Let’s break it down!

Groove Break Down

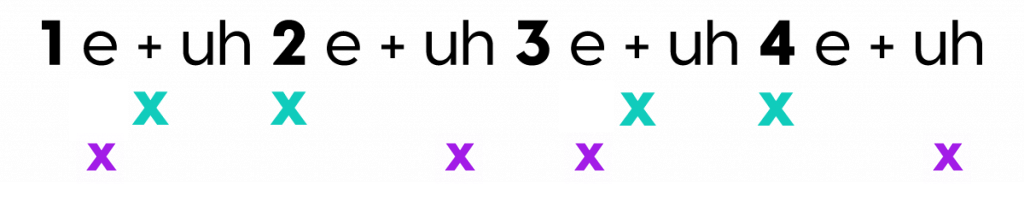

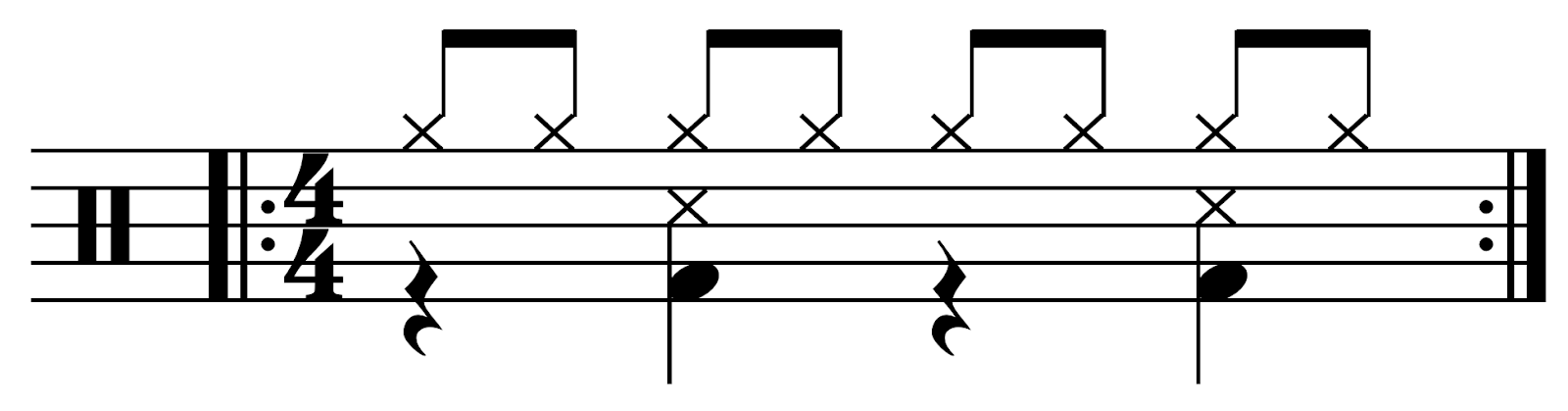

“TDCAU” is driven by a Jamaican Dancehall groove in common time. Dancehall is an evolution of Jamaican roots reggae that originated in the late 1970s. In utilizing this beat in a pop song, Jackson was very ahead of his time. While Dancehall had some mainstream success with artists like Sean Paul in the early 2000s, it wasn’t until the following decade that Dancehall style grooves truly became a mainstay in Western popular music; with artists like Drake, Ed Sheeran, and Rihanna now regularly employing this and other Afro-Caribbean rhythmic styles into their songs.

While there aren’t any hard and fast rules for what technically constitutes a Dancehall beat, the general structure is a combination of various elements borrowed from the Jamaican and Afro-Cuban diaspora. The beats are often characterized by a pushed “four on the floor” dance pattern wherein some quarter notes are offset to fall on upbeats and 16th notes, making use of polyrhythms.

“TDCAU”’s Dancehall influence can be heard most prominently in the snare pattern — notably when the snare is placed on an upbeat and its consecutive downbeat.

In typical rock, pop, and dance music the snare creates a hard backbeat on beats 2 and 4. In reggae, it’s not atypical to place snares on offbeats and 16th notes. Whereas traditional roots reggae avoids beat 1 in a “one drop rhythm” pattern, Dancehall does not.

This combination of a hard beat 1 with pushed or anticipated snares, hats, and claps, creates a unique Dancehall feel that is used here to great effect. The beat was likely programmed by either Chuck Wild or Brad Buxer, although Jackson is also credited with drum programming on the recording.

Arrangement and Melody

The song’s primary verse melody rocks back and forth between the root and minor third, then the second and flat seventh, giving us enough harmonic information to place the song firmly in a D minor tonality. This melody also outlines verse chord changes that will be introduced later in the song.

The synthesizer that enters at the start of the first chorus holds the minor third (F), creating a cool static harmony over the implied I- ♭VI ♭VII chord progression. While the melody and the synth imply chord movement, no actual chordal harmony is introduced into the piece until 1:44, when synth strings outline the progression with simple, two-note minor and major thirds.

After the second chorus, Jackson introduces a new melody in the post chorus, sung over a slight variation of the I- ♭VI ♭VII chord progression, which concludes with a V7 chord borrowed from the parallel major (D major). Borrowing the V7 chord from the parallel major when in a minor key is the most common use of “modal interchange” in popular music (in fact, in classical music, this is often considered the “standard” dominant chord, creating the harmonic minor scale).

Jackson also sings the minor third (C) over an A7 chord, which contains the major third (C#) as a chord tone. This sort of “allowed” dissonance” is found everywhere in the blues and creates a strong connection to the Black lineage of American popular music, where the minor and major third coexist and often appear simultaneously.

The first verse melody then returns, and after a third turn of the chorus, a choral arrangement provides more exhaustive harmony. The arrangement here begins with just two voices, outlining the root and third; the very same relationship created by Jackson’s two-note verse melodies earlier. Then, in the second half, a third, higher voice is introduced, outlining the A and C notes that we previously heard Jackson singing over that A7 chord, previously — a smart reuse of a secondary motif, or countermelody.

At 2:37, we hear the bridge for the first time. An interesting signifier of this section is how the progression uses the same chords as the chorus (♭VI,♭VII, I–), but arrives at the starting ♭VI chord from the V7 chord — or what’s known as a deceptive cadence. After just one pass of this progression, the mood shifts and swells from a since unseen Gm7 chord, back into another V7 to close out the bridge — a classic II-V progression, as found in countless jazz numbers, and another nod to the Black American musical roots of the tune.

That V7 is reintroduced to transition back into the verse, with Jackson again singing the third over A7. Only before, he sang the minor third (C), where now he’s bending upwards closer to the major third (C#), increasing the tension of the story he’s telling throughout the song. Although how we hear it still functions in the same way, Jackson’s note placement in between those two pitches is yet another reference to classic blues technique, from which this song finds its origins.

At 3:06, the song reaches a sudden and powerful climax, with distorted electric guitar and fast, sequenced pentatonic runs creating drama over the drum loop. The lead guitar here is actually being provided by none other than Guns N’ Roses guitarist, Slash!

Ostinato

At the very end of the song, underneath aggressive screaming by Jackson, a quartal ostinato enters over a static D power chord. An ostinato is a repeated melody or musical phrase that occurs over chord changes — here though, the chord acts more as a drone.

Voiced as double stops, this pattern persists even as the song concludes with D power chords underneath. Technically speaking, when the chord above moves to C major, we could almost spell this out as Dm11, but the third is missing, so it becomes a hybrid chord instead.

It feels less like an outro, and more like Jackson is building to a new section that we never get. It feels only semi-resolved, as if to suggest that our troubled journeys are not over yet — we still have places to go as a society, even after the song ends.

The roots of this repetitive technique can also be traced back to American blues music. While ostinato has been an orchestral technique employed by European composers for hundreds of years, the way Jackson uses a repeating lead over chord changes harkens closer to the Delta blues and its ubiquitous 12-bar blues form.

Whether through funk, soul, or Dancehall-infected synth blues, as in “They Don’t Care About Us,” Jackson finds ways to exhibit in macroscopic view the Black cultural legacy in the genealogy of American pop music time and time again.

Improve all aspects of your music with Soundfly!

Subscribe to get unlimited access to our premium online courses, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.