William Ryan Fritch is a composer, multi-instrumentalist, and songwriter who has been making music for film and releasing records professionally for about 7 years. I only came across his music recently but was immediately taken aback by his wide range of sounds and compositional tactics, that despite their different origins, all feel distinctly and familiarly similar. His music is visual in nature, and it’s why it pairs so well with picture, but it also has this ability to get straight at someone’s emotional core.

William’s also pursuing one of the most unique ideas for distribution I’ve come across — rather than writing and releasing one album at a time, he’s experimenting with a subscription model, where for an upfront commitment, he’ll send you 12 albums over 10 months. I checked in with him recently to learn about about why he makes the music he does and to hear more about his innovative subscription package.

Firstly, how did you get into scoring films and visual work?

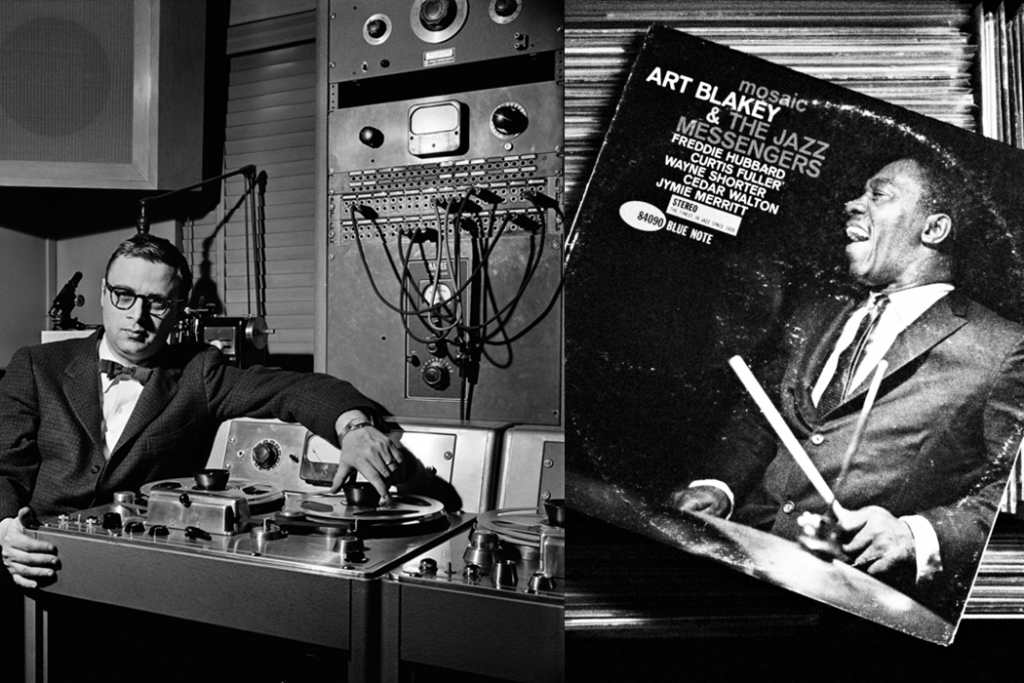

Since I was about 14 or 15 my “dream job” was to pursue a career in music for film, but it took me the better part of a decade to find out what that actually meant and how one could actually go about making a living as a composer for that medium. Initially, I began doing music for theatre, dance, and art installations for friends when I was still only competent in analog recording on my 4 tracks and reel-to-reels.

If you treat music like it’s your hobby, it will only be a hobby. If you treat music like it’s your job, it will be your job. If you treat music like it’s your life’s work, it will be your life’s work.

When I was about 21 (and finally developed some basic understanding of digital audio editing and syncing), I began doing small projects with friends who were interested in making their own films and videos. Making these gave me just enough of a portfolio to get the chance to work and intern for several months under the wonderful, LA-based composer Greg Tripi. Greg gave me invaluable insight into the process and the demands of professional film scoring. Seeing first-hand how the vast majority of large budget film music is made, I realized that I’d rather continue to develop the DIY approach I’d adopted for my records and slowly build my reputation, rather than take an understudy or assistant role for years as I learned to fully adopt the industry-standard skill sets most mainstream film composers rely on.

And how did you get your first few commissions?

My first couple commissions came all at once after my very good friend Megan Boone (now an actress on The Blacklist) recommended my music to several film makers she knew. They took a chance on me even though my resumé was limited and I thankfully was able to deliver music that made everyone involved happy. Shortly after I started getting some paying gigs in LA, I moved up to the San Francisco Bay area where I was introduced to the vibrant documentary filmmaking community around UC Berkeley’s School of Journalism. I began taking every gig I could, working myself to exhausting and pulling at least three all-nighters a week for the better part of three years.

That was what it took to survive, even then it was really rough. Eventually, I was able to start charging a rate closer to what my time was worth and choose which projects I wanted to take on.

Now that I’ve amassed a deep library of songs and compositions, I’ve started to have a little bit of success with my records and soundtracks. I find my hard work and obsessiveness are finally starting to pay off.

Tell me a bit about your subscription series.

I went through a big transition in 2013-2014 and ended up making an absurdly large amount of music in a very short time. The previous records I had released through Lost Tribe Sound were released and spaced apart in quite a standard fashion. If I had been touring regularly rather than composing full-time, it would have been sufficient to give myself and the label a puncher’s chance to break through and pique the interest of new listeners.

Thankfully Ryan from Lost Tribe Sound is one of the most enthusiastic and hard working people I know, and he was completely onboard with the shotgun approach I had in mind. He really spearheaded the whole thing. It ended up blooming into 12 albums and hopefully it is something that duly rewards the people who sign up for it.

How effective is this as a way of developing your fan community?

That’s a good question. I think we are still in the process of figuring that out ourselves. I wouldn’t take back any of the decisions we made in putting together this subscription series, and I know ultimately that it was worth the risk, but with the music industry still stuck in such a strange place of flux and uncertainty, I would hesitate to recommend any specific strategy unless it really fits within an artist’s particular productivity and business model. I wouldn’t have felt ok about pursuing a subscription model without knowing that I had enough content to exceed the expectations of those that purchased and will likely not do another subscription in the future unless there comes a time when I create more material that is very closely linked, both musically and thematically, and follows a distinct trajectory, artistically.

Growing up, who were the composers/artists that influenced you the most?

I grew up loving blues and R&B singers like Johnny Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Bill Withers, and because of the music my parents listened to, I knew the words to just about every soft rock hit from the 70’s (Cat Stevens, Carole King, etc.).

However, the moments that really changed my perspective were hearing Nina Simone for the first time when I was 15, discovering afro-beat music (I found King Sunny Ade’s first record at a Goodwill in high school.), discovering Jorge Ben’s music, and getting my first ECM record (Oregon’s Music for Another Present Era). These records all hit me at a pivotal time in my life, and while their discernible influence may not be obvious, they all served as an entry point for me into enumerable sources of musical inspiration.

Somehow I got myself stuck creating new arrangements for a Sammy Davis Jr. impersonator, and at one point I had to create 30 minutes of music for a soft core lesbian porn, just to make rent.

How has music helped to bring you strange, unexpected experiences in life?

The desire to make music and pursue it as a career has been the driving force that has brought just about every great and grievous experience in my adult life. Every turn in the circuitous and roundabout course I’ve taken thus far has been totally steered by my fixation on sound, and only recently have I been able to emotionally and psychologically resurface enough to see how crazy that route looks in retrospect.

The two years I spent in LA trying to “make it” has to be perhaps the most odd and confounding time of my life. I tried out to be the mandolin player and back-up singer for just about the worst modern country band you’ve ever heard, simply because they had paid practices. (I was required to wear a cowboy hat and boots for practices!) Somehow I got myself stuck trying to create and record new arrangements for a Sammy Davis Jr. impersonator’s album, and at one point in time had to create 30 minutes of music for a soft core lesbian porn for $200, just to make rent.

What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

A dear family friend and mentor, Jim Hurley (who sold me my first guitar), told me:

“If you treat music like it’s your hobby, it will only be a hobby. If you treat music like it’s your job, it will be your job. If you treat music like it is your life’s work, it will be your life’s work.”

I think the best way to discover your compositional voice is to develop and hone your editorial sensibilities.

What advice would you give others trying to explore and discover their own unique sound as a musician?

I think the best way to discover your compositional voice is to develop and hone your editorial sensibilities. To be able to separate yourself from the indulgences and excitement of sound, to honestly assess what in your musical decision making is rote and habitual and what is instinctual and extemporal. If you can free yourself from the fear of not sounding good while practicing or writing, it will teach you a whole bunch about what you actually like without relying on the staid and proven riffs we are fed throughout the entirety of our musical upbringings. It is hard to develop any true skills of restraint if the sounds you are culling from have already been repeatedly “pre-filtered”. Even the most traditionalist leanings still value good phrasing and that ineffable quality of “musicality” — qualities that only come from taking some risks and, whether they flop or fly, experiencing and charting the results.

Developing my editorial capacity and striving to attain the autonomy to realize my own “art” have been the most important, challenging, and rewarding processes for me.

Lastly, any future plans we should know about?

I have been writing a lot again after a few months of struggling to keep ahead of a feverish workload, which feels really good. I am mastering a new record at the moment and finishing a few films. But for most of the summer I will continue developing new material and keep sharpening my new live set before I head out to tour later this fall.

To hear more of William Ryan Fritch’s work, check out his Bandcamp. Get your hands on his Subscription Series through Lost Tribes Sound. And visit his website and Facebook page for updates on his upcoming tour.