+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

By Soundfly Mentor Tim Maryon

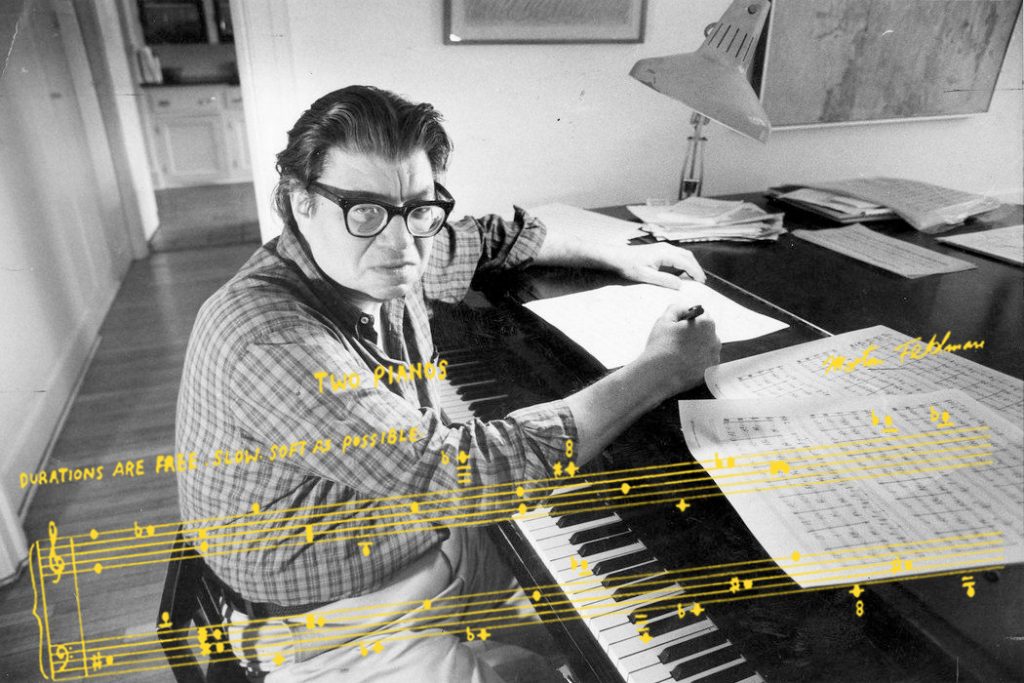

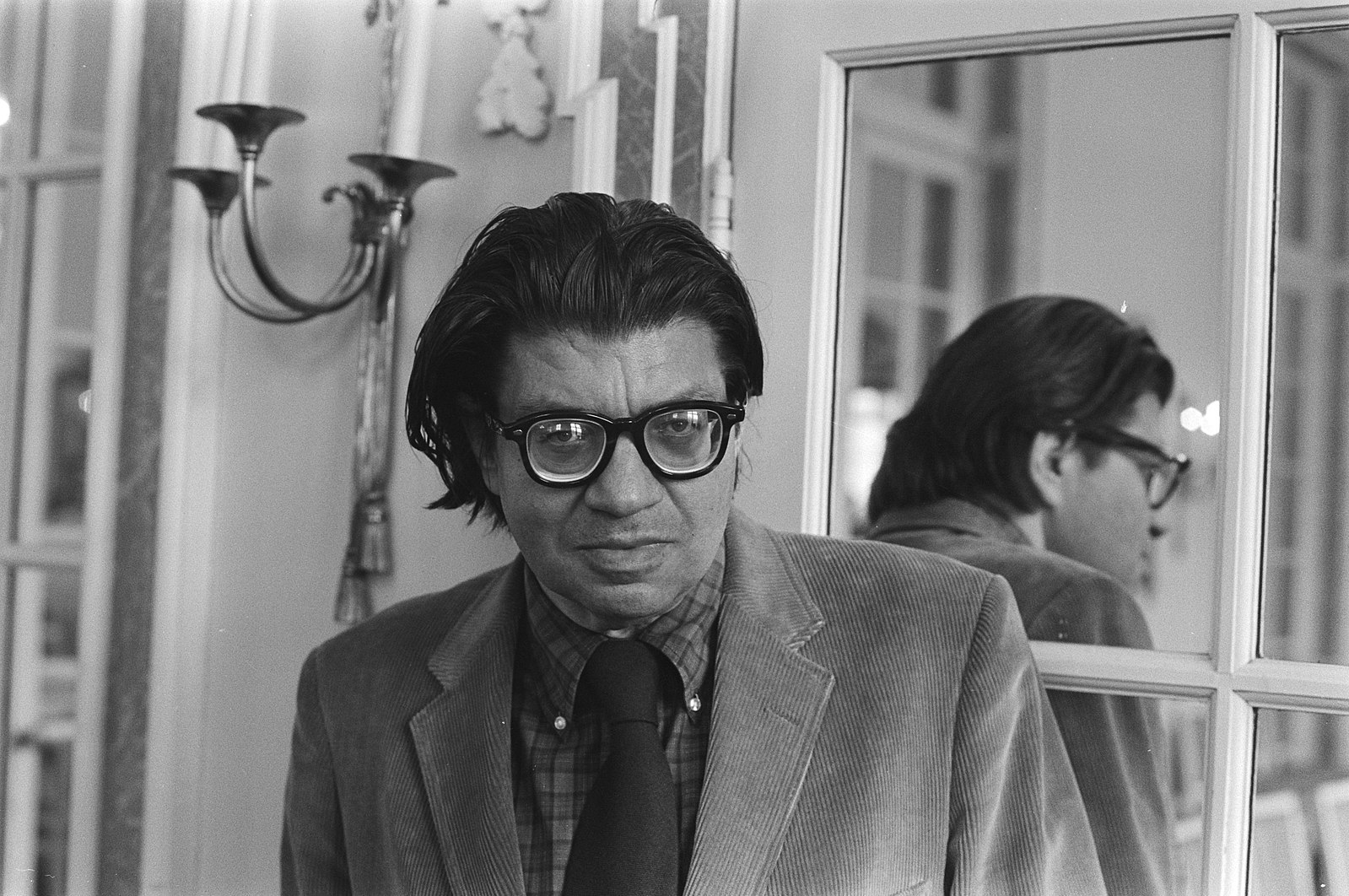

A student of mine recently said that they’d never been given the chance to “get into” famed American composer Morton Feldman. Daunted, and understandably so, by the sheer scale of his music, he was happy to resign himself in the opinion that Feldman’s music was simply inaccessible and frankly not worth the time it would take to explore it.

Believe me, it is worth the time. He was missing out!

Feldman’s work, especially his late chamber pieces are undeniably long. Really long… Really, really long! His works include an 80-minute Piano and String Quartet (1985), For Philip Guston (1984) written for flute, piano, and percussion, which clocks in at almost five hours, and the longest of them all, the six-hour String Quartet No. 2 (1983).

Yet something strange and beautiful happens when you listen to these works and let them pass over you — time is somehow altered and bent like refracted light through a prism. Your mind journeys through soft repeating patterns that seem never actually to repeat, and after 6 hours (which in most performance situations would be agonizing), you’re actually left wanting more.

When it comes to length, Feldman put it like this:

“My whole generation was hung up on the 20- to 25-minute piece. It was our clock. We all got to know it, and how to handle it. As soon as you leave the 20- to 25-minute piece behind, in a one-movement work, different problems arise. Up to one hour you think about form, but after an hour and a half it’s scale. Form is easy: just the division of things into parts. But scale is another matter.”

However, I feel it’s too often the case that, when in a pinch for time, the focus is put solely on Feldman’s longer form works, leaving some of his other great pieces unfortunately dwarfed. And it’s these other pieces that, for me, opened the door to the fascinating world of Feldman’s musical mind. His harmonic ideas are often not so complicated as to demand virtuosity of the performers, yet they produce dense emotional meshes in the audience’s response, especially when the performance setting is able to elevate the work spatially. Time and space are thus active parts of his work in sound, as well as elements that can be playfully reexamined throughout the listening experience.

So pencil in some room in your diary and find a comfy chair; here’s a beginner’s guide to help you navigate the work of one of America’s greatest 20th century composers.

If both the length and harmonic vocabulary of Feldman’s work seems daunting, I suggest starting here, with his work Samoa (1968). Copland-esque at times, yet with all the logic and nuance of Feldman’s aesthetic, Samoa, one of his lesser-known works, has many musical familiarities and so seems a fitting place to start. Listen to the tone painting here, and how the ensemble always feels like they’re wandering, but moving tightly together.

Madame Press Died Last Weekend at Ninety (1970) is written for a chamber ensemble. This short ditty is touchingly simple, yet has a harmonic expansion throughout the 5-minute piece that gives you a glimpse into a deeper harmonic language that is the hallmark of Feldman’s larger body of work.

The repetitive pattern played by the flute in the middle section always makes me think it’s a reference to the tape looping practices of his electroacoustic contemporaries like John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Terry Riley. Check this one out!

Rothko Chapel (1971) — possibly one of Feldman’s best known works, composed for viola, wordless chorus, percussion, and celeste, it has an almost holy quality, with its isolated chords, fragmented melodies, and thick cloaking silence. Moderate in length and equipped with an overarching sense of solitude, this piece seems to draw you in, leaving the listener suspended by its stillness.

Written the year before his death, Feldman’s late work for orchestra, Coptic Light (1985), is a wonderful web of patterns that ebb and flow, expanding and contracting throughout the 21-minute experience. Although challenging in some ways, this work is of a manageable enough length to maintain focus throughout without becoming bogged down by it.

For Bunita Marcus (1985) is an incredible work for solo piano that draws us ever closer to the sound of the performance space, the inside of the instrument, and the air around it. Sparse and with little dynamic fluctuation, this work well encapsulates some of the elements that define his compositional and emotional palette. In his own words, Feldman writes:

“In my music I am… involved with the decay of each sound, and try to make its attack sourceless. The attack of a sound is not its character. Actually, what we hear is the attack and not the sound. Decay, however, this departing landscape, this expresses where the sound exists in our hearing — leaving us rather than coming towards us.”

Patterns in a Chromatic Field (1981), for piano and cello, in contrast to much of the work in his oeuvre, is bursting with energy and drive. At just over 80 minutes, this piece is a great introduction to Feldman’s more mature work, and the extents of his creative range with the limitation of using only two instruments. It’s among his most respected and revered works, and it’s a long time personal favorite. The way the piano and cello dance around each other, each note descending toward both silence, and the subsequent abstract call-and-response is a joy to listen through in its entirety.

Crippled Symmetry (1983) was written for his group, Morton Feldman and Soloists, during his time as Head of Composition at the University of Buffalo. Crippled Symmetry has a wonderfully supple quality that unfolds organically throughout its 85-minutes. There is no full score to this piece, so the three players, each with their own notated parts, don’t really ever know when to synchronize their playing. Therefore, it becomes a work of listening and measuring, as much as playing and following.

According to classical music journalist, Andrew Clements:

“The lack of precise co-ordination creates the sense of every sound constantly being reassessed and placed in a slightly different context. The same idea acquires a whole spectrum of inflections as it’s repeated, and even the most commonplace musical shape — a rising major scale for instance — can seem utterly strange and freshly minted. “

For Phillip Guston (1984) was composed for his close friend, the abstract impressionist painter, Phillip Guston. This is another one of Feldman’s best known works, and the title of which very clearly brings together the important generation of American artists working across disciplines who advocated for new artistic vernaculars to call their own. Very, very quiet and very, very long, this work for flute, piano, and percussion is a master class in the exploration of ways that painting and tone painting can create the same emotional experience in an audience’s ear and eye.

To that end, Feldman once said:

“If you don’t have a friend who’s a painter, you’re in trouble.”

Violin and String Quartet (1985), another work written in one of Feldman’s most productive years, has been said to encapsulate Feldman’s minimalist-leaning aesthetic in its purest from. Two hours of sighs, whispers, murmurs, and tremolos from the string quartet, are made even more etherial by a solo violin floating above. This ghostly music is a most intimate encounter with sound.

String Quartet No. 2 (1983), at almost six hours in length, is widely considered his greatest masterpiece. If you’ve made it this far, well done! Rarely performed, and for understandable reasons, this work completely alters your perception of time. As we’re drawn in by the slowly repeating patterns, time itself begins to slow down, leaving you transfixed in a meditative state. Like breathing, the piece expands and contracts as you float through the closest sound to silence.

So there we have it! Feldman was a brash, larger-than-life New Yorker who wrote the softest, most intimate of music. His oeuvre should never be shied away from, but entered like a hall of mysterious doors. For those who have found difficulty in approaching this titan of the avant-garde, or found it tricky to find a way in to his vast world, I hope this helps, and I hope you, too, can now enjoy the great world of Morton Feldman!

This article was written by Soundfly Mentor Tim Maryon! If you’re interested in working with Tim on your next music project, fill out this form to tell us about your goals and be sure to mention his name in your response!

Get 1:1 coaching on your composition from a seasoned pro.

Soundfly’s community of mentors can help you set the right goals, pave the right path toward success, and stick to schedules and routines that you develop together, so you improve every step of the way. Tell us what you’re working on, and we’ll find the right mentor for you!