+ Turn your unfinished ideas and half-developed loops into full, compelling songs with Soundfly’s online course Songwriting for Producers. Preview a lesson for free and subscribe for unlimited access for only $39!

One of the best things you can do as a working producer is to analyze music by the artists who inspire you. This will help you understand how they build their tracks, and develop their ideas for when you start working on how things are arranged and orchestrated.

There are often structural details that aren’t immediately obvious, so it’s worth taking some time with this and thinking about a song from as many angles as possible. You can get as detailed as you’d like, but here are some things we recommend looking at to get started:

- Harmony. New chords can mean we’ve moved from one section of a song to another. There are exceptions, but it’s usually a good clue.

- Melody. The move from a small-ranged, safe melody to something full of leaps into the stratosphere, or some other major change, can often mean we’re in a new section of the song.

- Lyrics. Whether things are detailed and wordy or simple and repetitive can tell you a lot about a section of a song.

- Fills. Transitions and other types of ornamentation can also be a clue that we’re either in a new section or about to get there.

- Number of measures. If a section defies symmetrical expectations (like being more or less than eight bars) and that feels interesting to you, look at what else is going on and see if you can figure out why that works as well as it does in that moment.

- Repetition. What does and doesn’t get repeated can be revealing. Are you running into the same lyrics over and over? They could be part of a chorus or refrain. Is there one chord in particular that keeps showing up? It’s probably pretty important to the key of the song.

Let’s look at some strategies for breaking songs down into their structures.

Common Song Structures

When it comes to organizing the structure of your song, where and when certain sections come in, and the roles they play as your song develops, there are a few ways to go about this. Some of the most common types of song forms are just variations of verse, pre-chorus, and chorus, with the occasional bridge or solo thrown in, especially in pop music.

Let’s look at a couple, and listen to songs that exemplify those various models.

Song Form #1

Intro • Verse • Pre-Chorus • Chorus • Verse • Pre-Chorus • Chorus • Bridge • Chorus • Outro

This is a very classic song structure that can be found in everything from James Taylor to Ariana Grande. Here are some recent songs that use this structure (or something similar):

- “break up with your girlfriend, i’m bored” by Ariana Grande

- “Finesse (Remix)” by Bruno Mars and Cardi B

- “Shape of Me” by Ed Sheeran

- “Without Me” by Halsey

- “Better Now” by Post Malone is similar to this except that it starts with a chorus and drops the middle pre-chorus.

Song Form #2

Intro • Verse • Pre-Chorus • Chorus • Verse • Pre-Chorus • Chorus • Outro

A lot of pop, hip-hop, and electronic tracks are skipping the bridge these days. You can hear this song form or something similar in the following tracks:

- “Latch” by Disclosure & Sam Smith

- “Redbone” by Childish Gambino also follows this pattern but with an epic outro that could also maybe be considered a bridge.

- “Chandelier” by Sia is close, but has virtually no intro and a “post-chorus” section that changes the melody, but uses the same chords and instrumentation as the chorus after each chorus.

Song Form #3

Intro • Verse • Chorus • Verse • Chorus • Outro

Finally, why make things complicated? There’s nothing wrong with a very simple, no-frills structure, especially if you have a catchy hook on which you’re seeking to rely heavily. This seems like a fairly popular structure for hip-hop tracks in particular.

- “HUMBLE.” by Kendrick Lamar

- “Bodak Yellow” by Cardi B follows this pattern, but starts with an extra chorus.

- “rockstar” by Post Malone with 21 Savage also adds an extra chorus upfront.

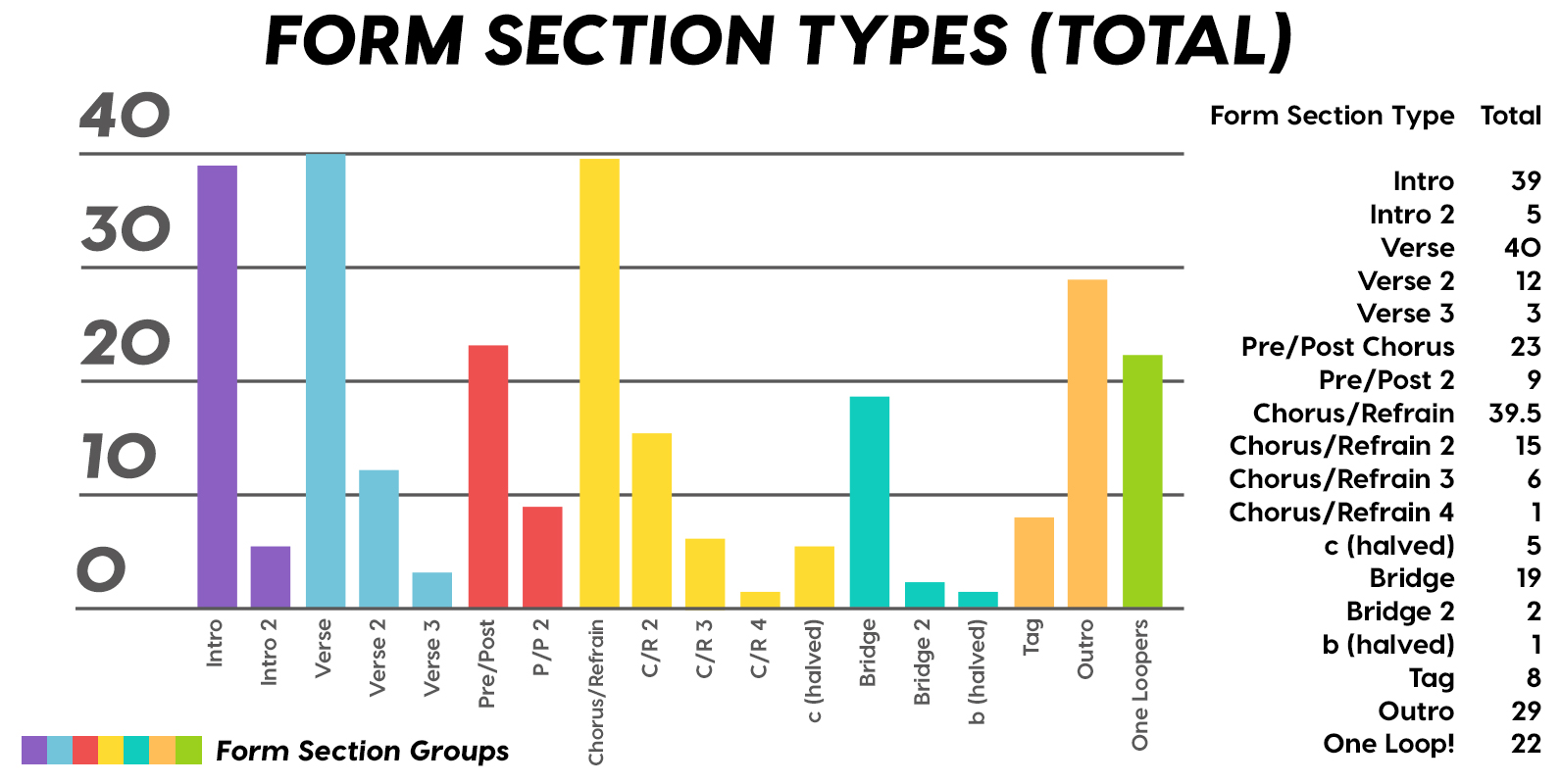

You may have noticed by now how these sorts of structures really can be plug-and-play to some extent. In our analysis of 2018’s top Billboard tracks, we saw how these different sections pop up again and again, some more than others, but with many different variations. Here’s a chart from that analysis that shows how often each section appeared throughout all the songs we looked at:

One particularly interesting thing to point out here is that very last green bar — “One Loopers.” That’s not actually a reference to the form, but it’s related to it. It means that more than half of the 40 songs we looked at that topped the Billboard charts in 2018 were based off of just a single loop that continued for the entire track. In those cases, the different sections were delineated less by harmonic changes or big structural differences but instead by the melody, the instrumentation, or both.

It truly is a producer’s world out there!

+ Learn production, composition, songwriting, theory, arranging, mixing, and more — whenever you want and wherever you are. Subscribe for unlimited access!

Other Approaches

So far, we’ve kept to pretty mainstream pop tunes, but when we start to move away from those, things can get murky pretty quickly. For instance, while verses and choruses might be easy to recognize in a big pop anthem, how they function in an electronic dance song might not be as clear. Or how would you describe the form of something like “A Day in the Life” by The Beatles? It’s basically two entirely separate songs smashed together, so there’s no obvious “verse” or “chorus” section. Same thing with Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode,” but for three songs’ worth!

To get around this problem, we’ll sometimes give sections names like “A” or “B” instead of “verse” or “chorus.” Let’s look at a few structures in this vein.

Strophic (AAA)

This is one I’m sure you’re familiar with, even if you might not have known its fancy name. It’s also sometimes called Verse-Repeating or Chorus form, because it essentially repeats the same section, but with new lyrics each time. If we’re thinking of things in terms of “A” sections and “B” sections and so forth, this would just be multiple As, one after the other.

In essence, “Mary Had a Little Lamb” is an example of this structure. It’s the same melody again and again, but with different lyrics. Another famous example might be “Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan.

Classic/Standard (AABA)

This form is super common in classics and jazz standards. You start with a section, repeat it, move on to something else, and come back to that first idea again. Most recordings of standards like Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm” use this form, sometimes featuring additional repetition to extend the song. Two other famous examples are “All I Have to Do Is Dream” by The Everly Brothers and “Yesterday” by The Beatles.

ABAB and So On

One thing you might have noticed is that we haven’t seen a ton of instrumental music so far. As previously stated, it’s not always as easy to identify a verse and chorus in instrumental music, so thinking in terms of Section A and B can be more useful. But given that, there’s really no limit on what sort of structures you might see:

- “Alone in Kyoto” by Air has two basic ideas that each repeat and then a third one that ends the song, so you could think of it as ABABC, with an intro and outro on either end.

- “Oh Why” by Balam Acab could be heard as ABC, where half the song is one idea, followed by two variations that close it out and increase the energy.

- “Avril 14th” by Aphex Twin might be heard as ABCADA. The central idea repeats roughly three times, but in between there are a few variations that each feels like its own section.

Developing a Single Idea

While the basic idea of sectional form can be stretched pretty far, it’s not uncommon to hear songs with additional types of sections. Pre-verses, post-choruses, breakdowns, ad-libs — there are plenty of examples of alternate forms.

One of them that’s common in electronic and instrumental music is the development of a single idea over time. It’s also common in dance music, ambient music, and minimal music, and tends to work well with slowly developing sounds or textures. This kind of technique of form is also common in reggae, in certain kinds of West African music, and in East Indian classical music, among others — all musics that attempt to evoke transcendental states and trances while exploring a particular mood or emotional space, and utilize melody and rhythm to drive the song forward.

A classic example is the LCD Soundsystem song “All My Friends.” The song develops extensively, without an obvious lyrical structure. There are certainly repeated melodies, various layers coming and going, and a strong lyrical narrative, but it never deviates from that repetitive piano part.

At the opposite end of traditional form is through-composition — essentially a style of composition that doesn’t repeat sections of music, lyrics, and might not even repeat melodic themes. It could be argued that the lyrics of “All My Friends” is through-composed.

This is common in classical music but appears occasionally in pop music. A particularly famous example is the Beatles song “Happiness is a Warm Gun.”

This is still sectional, but each section happens linearly, without repetition. You can represent this sort of form as something like: Section A, B, C, D, etc.

The main takeaway here is that you don’t have to follow a typical form if you don’t want to! There’s so much great through-composed music, and sometimes, it can be really freeing to embrace this kind of writing.

Through-Composition in Electronic Music

Since many styles of electronic music don’t include lyrics, it lends itself well to the endless development of an idea. Andrew Bayer’s “Counting the Points” is a beautiful example of this sort of repeated development of a theme or idea.

It’s important to keep in mind that a lack of lyrics doesn’t mean that a piece is formless. Things are still frequently organized into typical sections of four, eight, 16, or 32 bars.

At the end of the day, it’s good to understand your intentions for a song as you establish its form. Each type of song section can serve a different purpose. If what you’re working on isn’t sitting right and you can’t find any specific problems with harmony, lyrics, or any of the other components we’ve discussed, it may just be that you need to revisit the overall structure of the song.

Do you have a two-minute number that somehow feels like it’s dragging on without going anywhere? Maybe you need to add a bridge.

Does the move from your verse to your chorus feel overly sudden, leaving things disjointed? Consider using a pre-chorus to ease that transition.

Do you want a place for the audience to clap along? Sometimes doubling up the last chorus can accomplish that nicely.

Want to get all of Soundfly’s premium online courses for a low monthly cost?

Subscribe to get unlimited access to all of our course content, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.