+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

By Sam Zerin

The legendary music theorist, supervillain, and Family Guy character Stewie Griffin once said that the beginning of a song should “feel like home.” As he demonstrates in the clip below, you can adequately achieve this cozy, domestic atmosphere harmonically by starting with a I chord (he sings, “Your cozy house where you live”), following with a IV chord (“everything looks okay; maybe I’ll take a walk outside”), then a V chord (“walking around outside”), and eventually making your way back to the I chord (“back to my house!”)

Take me home.

As basically any music theory teacher will tell you, I and V are the keys (pun intended) to establishing this homelike sonic atmosphere. For example, Mozart’s Piano Sonata in C Major, K 545 opens straight off the bat with a I V I progression, followed by IV I V I. Isn’t that wild? Six of the first seven chords of the piece are either I or V! Mozart’s not fooling around, he really wants to take us home… to Vienna or something.

If you’ve ever listened to rock or pop music, you’ve probably heard another progression that highlights these two chords as stars of the home base, albeit in a different sounding manner: I V VI- IV.

Check out this video to hear 65 songs that use this progression.

But here’s the thing. What if… you don’t want your song to start in a nice, cozy home? Or, I should say, what if you want to add some color to your house, so it’s not so white-picket-fencey? Or what if you wanted to start in a broken home, a complicated architectural home, or a dream home, floating somewhere between reality and fantasy?

Now that we’ve gotten these first two sort of vanilla progressions (I V I and I V VI- IV) out of the way, here are three “non-cozy” alternatives for starting off your newest song.

+ Learn production, composition, songwriting, theory, arranging, mixing, and more — whenever you want and wherever you are. Subscribe for unlimited access!

Oscillate between chords that are a tritone apart.

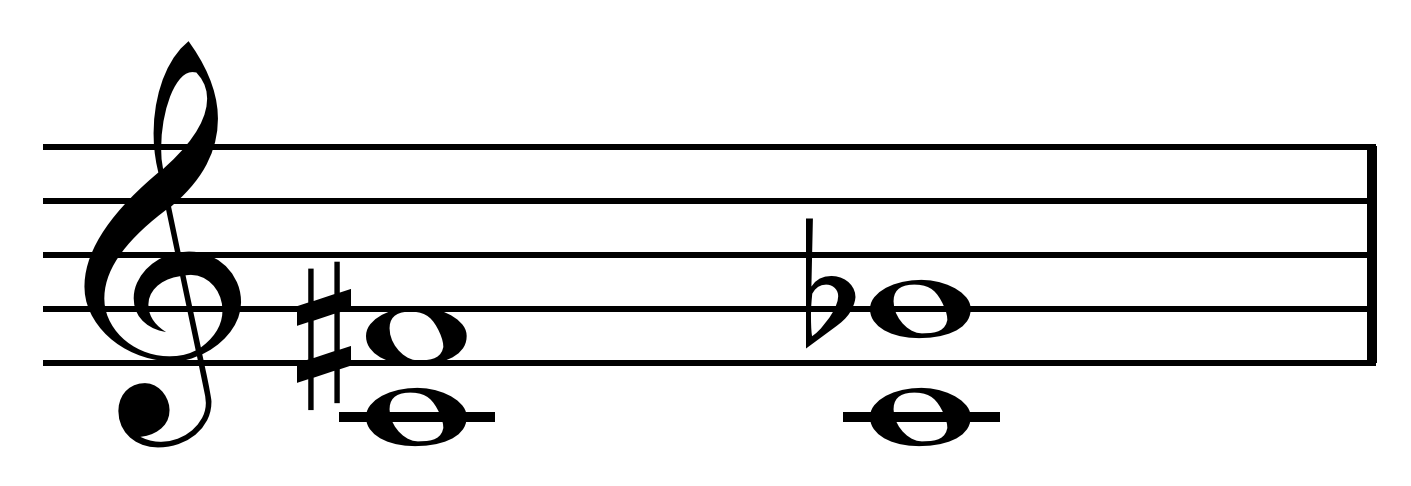

For hundreds of years, the interval of a tritone, which is three whole steps (e.g., C to F#, or C to G♭) has been called “the devil in music.” It has a harsh, jarring, and otherworldly effect. Yet despite this, “Bach used it all the time, and he wrote the greatest Christian music in history,” as musicologist (and instructor of Soundfly’s A Conversation with the Blues course) Vince di Mura points out in this video.

For years, though, it was traditionally avoided when writing melodies. When two chords are a tritone apart, that harshness effect is amplified — it can sound like a sudden, out-of-tune key change.

However, Olivia Newton-John’s “Magic” (1980) is a fantastic example of how tritone-related chords can be used at the beginning of a song to establish a surreal mood. The song begins with a two-bar vamp that simply alternates back and forth between a D major chord and a G#7 chord (D and G# are a tritone apart). But that’s not all. By constantly slipping back and forth, back and forth, between these two chords, the tritone’s jarring effect becomes almost normalized, creating an otherworldly atmosphere that fits with the lyrics.

Oscillate between IV and V, and don’t resolve to the tonic!

Once upon a time, when I was teaching music theory at Brown University, I devoted almost two entire class periods to analyzing “Part of Your World” from Disney’s The Little Mermaid. It’s an awesome song — take a listen (you know you want to!).

Part of what makes this song so awesome is that the music’s harmonic structure so perfectly captures Ariel’s longing to live somewhere else. We’re not starting in a happy, cozy home here. Ariel’s home is a prison — a boring, lonely world from which she yearns to break free. Believe it or not, there is not a single I chord until bar 31, when Ariel first mentions the new home she wants to live in: “I wanna be where the people are.”

So this song begins with eight measures that do nothing but alternate between IV and V, back and forth, back and forth, not going anywhere… because Ariel’s not going anywhere. We feel her situation before we can even put words to it. This is followed by a few meandering chords that highlight the minor aspects of the F major scale: an A minor chord (III-), a D minor chord (VI-). Then we have another round of IV V IV V, followed by some jazzy stuff — and then, at last, a big cadence leading finally to the I chord. Ah, resolution.

Use the minor iii chord to make a major key sound sad.

Major is happy, and minor is sad, right? Well, not necessarily.

As Jake Lizzio points out in a brilliant video, the mediant chord (III-) is a powerful tool for sounding sad in a major key.

Jake uses a great song example to explain this one. “Hey There Delilah” by the Plain White T’s begins by simply alternating between I and III- (aren’t ostinatos great?), it continues on with a cadence that plays around with the minor vi chord, and then starts alternating I and III- again.

I III- I III-

VI- IV V VI- V

I III- I III-

Now it’s your turn! Try these out, and then let us know which one is your favorite and why. Got others? Share them in the comments!

Want to get all of Soundfly’s premium online courses for a low monthly cost?

Subscribe to get unlimited access to all of our course content, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.

—

Sam Zerin is a composer, pianist, and all-around music scholar based in Providence, RI. He runs Social Media Music Theory, a project that raises awareness of the vast new world of music theory podcasts, blogs, YouTube channels, Pinterest boards, and more. He also teaches music theory at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, while completing his PhD in musicology at New York University.

Sam Zerin is a composer, pianist, and all-around music scholar based in Providence, RI. He runs Social Media Music Theory, a project that raises awareness of the vast new world of music theory podcasts, blogs, YouTube channels, Pinterest boards, and more. He also teaches music theory at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, while completing his PhD in musicology at New York University.