+ Learn from Grammy-winning pop artist Kimbra how to harness the full creative potential of your voice in song. Check out her course.

Let’s get right down to it. You want to write catchier melodies that appeal to more listeners, but you don’t want them to sound formulaic or trite, and you’re not totally sure how to do it.

So how do we write catchy melodies? Is there a perfect formula that works every time? Are there shortcuts?

The short answer is that the melody should be memorable yet crafty. It should be interesting, but not too complicated. It should be simple, but not basic. Writing a good melody depends on a very delicate balance in the end.

Melody writing is one of the most scrutinized areas in songwriting, especially when combined with how melody interacts with other elements of the song, such as harmony, rhythm, and form. Certainly with so many songs being released every single day, it’s hard to be able to stand out regardless, and even more so on the basis of your music alone.

So we’re going to talk about melody writing from a very particular angle today, how motifs and precise repetition can be used in tandem with your melody to create a truly memorable end result — a bit more on this below.

But first, for all you singer-songwriter-producers, Soundfly just launched a brand new course with Kimbra, in which she herself demystifies her variety of vocal techniques and the creative inspirations behind her most beloved songs. Go check out this awe-inspiring new course, Kimbra: Vocal Creativity, Arranging, and Production.

Motivic Development Techniques

A great melody always starts from a motif. A motif is a compact cluster of musical information, and can be smaller than a melody itself. Motifs can be modular, so they can shape the rest of a song around them, as well as move around the song in different ways. We’re going to talk about seven techniques for developing a motif, each with a specific song reference that exemplifies its use.

1) Direct Repetition

Direct repetition is used for making a phrase longer by repeating the same motif, sometimes a few times. A great example is “We Don’t Talk Anymore” by Charlie Puth and Selena Gomez. In this song, the main motif repeats three times in the chorus. In fact, Puth creates almost an entire chorus by taking this simple refrain-like phrase and repeating it a few times.

Whether it’s a great melody or not, direct repetition can help your melody get stuck in listeners’ heads. Just make sure not to overdo it!

2) Antecedent-Consequent

Antecedent-consequent is a bit like question-answer format. It’s an effective way of developing a melody where two motifs complement each other. A textbook example of antecedent-consequent exists in Radiohead’s “High and Dry.”

In the first phrase of the first verse of the song, the antecedent is: “Two jumps in a week, I bet you think that’s pretty clever” (0:28). Then the consequent follows: “Don’t you boy?” This gives a feeling of resolving. The next phrase starts with the antecedent again: “Flying on your motorcycle, watching all the ground” and it is answered with: “Beneath you drop.”

Musically, a great way to build your antecedent phrase is to finish your motif with an unstable scale degree, like a second or fourth, as these feel uncertain and unresolved. Then your consequent motif can come in to resolve the phrase– with degrees like a first, third, or fifth.

+ Enjoy access to Soundfly’s suite of artist-led music learning content for only $12/month or $96/year with our new lower price membership. Join today!

3) Sequence

A sequence is when you move your motif up or down to different pitch levels without disrupting the pattern. Led Zeppelin’s “Heartbreaker” is a great example of a sequence. The main motif, which appears from 0:00-0:05 is moved up by a whole step at 0:16-0:20. At 1:31, the motif is moved up a whole step higher again, so in total, two whole steps above of the original motif.

4) Extension

Extension is a technique to make the end of the motif stronger and more effective. A good example can be found in the chorus of “Golden” by Jill Scott. In “Golden,” the main chorus motif appears at 0:38: “Living my life is golden.”

Using direct repetition, Scott repeats the motif a few times, and only at 0:47 she adds to it: “Living my life is golden, golden.” The second “golden” is not in the original motif, which makes it an extension.

5) Truncation

Truncation is used to transform a motif into a smaller phrase. A typical example is the chorus of “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” by The Police. The main chorus motif is: “Don’t stand so close to me.” However, the chorus, which starts at 1:04, appears as: “Don’t stand, don’t stand so, don’t stand so close to me.”

Since the main motif is “Don’t stand so close to me,” from this we induce that the main motif is first truncated to “Don’t stand”, then truncated again into “Don’t stand so.” Then the two truncations, plus the main motif are sung together, which makes up the whole chorus. As seen from this example, a bigger motif can be broken down into smaller phrases to construct bigger melodies and even a whole chorus section.

6) Fragmentation

Fragmentation is also a type of truncation, where we truncate a single word to smaller syllables or pieces. A famous example of this is “Umbrella” by Rihanna and JAY-Z, where at the end of the chorus, she sings the phrase: “Umbrella, ella, e, e.” She breaks a single word down to various fragments.

7) Rhythmic Displacement

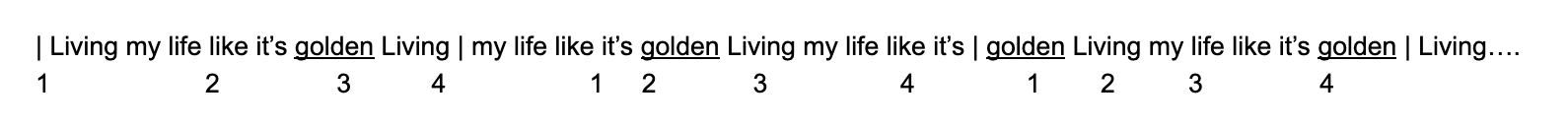

Last but not least, rhythmic displacement is perhaps the craftiest of all the motivic development techniques. This technique uses the same motif starting in different beats of the song, and in fact we can return to Jill Scott’s “Golden” once again to hear it play out.

“Golden” is a song in 4/4 time signature. The main motif of the chorus is the phrase: “Living my life like it’s golden,” which consists of three beats. But how do you use a three-beat phrase in a four-beat song?

The writers took advantage of this situation and here’s what they thought: on the 4th beat, what if we restarted the phrase? This means that the words and melody would now fall into different places every time the cycle continues. So here’s what the whole thing looks like:

A great melody is sometimes made by taking the simplest motif and presenting it in a crafty manner using the seven techniques above. Keep in mind that there are many more techniques available to you, and as you keep listening to your favorite songs, you might discover there are even more approaches you can use.

If you continue approaching songwriting with such critical listening, then you are bound to develop your melody writing skills and to make great music!

Don’t stop here!

Continue learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Ryan Lott, Com Truise, Jlin, Kiefer, RJD2, and Kimbra: Vocal Creativity, Arranging, & Production.