+ Take your modern jazz piano and hip-hop beat making to new heights with Soundfly’s new course, Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production!

This article originally appeared on Ethan Hein’s blog.

Is this the coolest pre-Revolver Beatles song? In terms of notes on the page, it very well could be.

My daughter and I managed to sing the harmony parts together the other night. She has a good ear for a seven year old, but also, the harmonies in that song are so clear and intuitive, it’s like they want to help you sing themselves.

My kids got hip to the tune from watching A Hard Day’s Night.

According to Songfacts, when Paul introduced “If I Fell” on tour, Lennon liked to add the word “over.” Songfacts also claims that the song sounds like John Dunstable’s motet “Quam pulchra es” from the fifteenth century, but I don’t hear that at all.

Here’s my chart:

There is a lot happening here!

So, let’s talk about the harmony.

The first chord you hear is E♭m, and the melody walks up the E-flat minor scale. Ah, you think, we are clearly in E-flat minor. But then the second chord is D, which makes no immediate sense at all. The move from E♭m to D is a slide transformation in Neo-Riemannian theory: E-flat moves down to D, G-flat stays enharmonically the same as F-sharp, and B-flat moves down to A.

That is cool voice leading, but chords in rock are supposed to function, and this one does not.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Where Have All the V Chords Gone? The Decline of ‘Functional’ Harmony in Pop.”

Also, John’s melody over the D chord outlines most of the D whole tone scale, which just kind of floats in tonal zero gravity. The third chord is D♭, and the melody is D-flat in octaves. Oh, so maybe we were in D-flat major this whole time?

That retroactively makes sense of the first two chords: E♭m is the ii chord, and D is a tritone substitute for the V chord. The fourth chord, B♭m, is the regular old vi chord in D-flat major. Okay, good, we know what key we’re in now.

Next, the intro loops back to the E♭m and D, but then… surprise!

The line “just holding hands” is on Em and A, the ii and V chords in D major. We just modulated up a half-step, which is wildly unconventional thing for a rock song to do three quarters of the way through its INTRO! The weirdest thing is that the shift to the key of D does not happen on the D chord itself, because you have been primed to hear that as a substitute dominant chord in D-flat major.

I don’t hear the key change really taking affect until the A chord. So cool!

The verses are harmonically much more conventional.

They start by walking up and down the D major harmonized scale: D, Em, F#m. On the way back down to Em, John and Paul sing an implied F°7 chord, but it isn’t present in the guitar part. The real magic here is the vocal counterpoint, so let’s zoom in on that. On the words “If I give my,” John and Paul are singing a sixth apart. On “heart,” John jumps down so they are singing a third apart. They are still a third apart on “to.”

Then on “you,” Paul keeps going down while John steps up, so they are singing a fifth apart. The rest of the line is in unison. That is not “correct” counterpoint writing, but it sounds terrific.

Things get even more magical at measure 27, the beginning of what I am calling the chorus. On the word “her,” the unison line splits apart so John and Paul are singing in thirds. The underlying chord is D9, and John is singing the ninth on top of Paul’s seventh.

Buttery!

And speaking of buttery… We here at Soundfly are pretty jazzed about minor 9 chords, which (like butter) basically work on everything. Take a look:

On the words “cause I couldn’t stand the,” John and Paul sing their way up the G major scale in thirds (or D Mixolydian mode if you prefer to think that way). On the word “pain,” Paul steps from A down to G, the chord root, so no surprise there. But John jumps all the way down from F-sharp to B. This creates a lovely sixth, and also sets up the next bit of musical microdrama.

On the word “and,” John stays on B, and Paul jumps down to D, so now they are a close third apart. On the word “I,” Paul stays on D, and John steps from B down to B-flat, anticipating the chord change from G to Gm. On the words “would be sad if our new,” John and Paul sing in aching close thirds up the D natural minor scale.

On the word “love,” things brighten back up, as Paul steps from G down to F-sharp, putting us back in D major, while John jumps from E down to A, making a resplendent sixth. Finally, on the words “was in vain,” John pedals the A, while Paul climbs from E up to G.

That last interval is a flat seventh, and you don’t hear too many of those in two-part vocal harmony in rock!

Alan Pollock points out a some more noteworthy musical details.

Quite unusually for Lennon and McCartney, we find here an old fashioned kind of intro in the style of, say, Gerswhin or Porter. It’s fully developed as a section unto itself with material not heard in the remainder of the song, and set-off from what follows by a different texture in the instrumental backing track; examples of the latter include John’s four-in-the-bar rhythm guitar strumming punctuated on the downbeats by George, and Ringo’s delayed entrance until the verse.

The phrase “sad if our new love” contains an unusual melodic cross-relation between the F-natural (on the word “our”) and the F# two words later on “love.”

The lyrics are deceptively simply and full of elliptical, ambiguous word play so typical of John’s best work. Examples abound — the dangling question (“[would you] help me understand?” — understand what??), the use of “to”, “too” and “two” in close proximity to each other, and the non-sequitur of the second repeat of the verse extension (“‘cos I couldn’t stand the pain”) when it follows the line “she will cry when she learns …”

Alan Pollock hears word play, I hear some lyrics that were chosen more for their sound than for their meaning. Many Beatles songs make perfect sense when you hear them and very little sense on the page. Sometimes they are deliberately going for surrealism, but this song predates their interest in psychedelic drugs; it’s just illogical.

That’s okay! There is more than enough meaning in the music.

Lots of people have covered “If I Fell.” I remember hearing Maria Muldaur sing it in a show and being knocked out by it. Most covers stay faithful to the original, and when they don’t, I generally wish they would.

Roberta Flack’s version is my favorite of the not-so-faithful versions.

How would you have written this song?

I teach songwriting at the New School, and we talk about the Beatles a lot. If you wanted to write a song like “If I Fell,” how would you go about it? Anybody who has been to music school can write two-voice counterpoint in a way that sounds “correct” but blandly forgettable.

So maybe you should forget about pencil and paper and try to work things out by ear? I have heard untrained singers sing plenty of nice harmonies by ear, but they aren’t usually as hip and ambitious as the ones the Beatles came up with. John and Paul have a particular blend of sophisticated and unsophisticated that is hard to replicate.

By the time they wrote “If I Fell,” John and Paul had been singing and writing together intensively for eight years, starting when they were teenagers. Their creative relationship would burn itself out just a few years after they recorded this tune, but at that moment, they were practically telepathic.

How would you possibly cultivate a partnership like that with someone? Would it even be possible if you didn’t start as kids? If you hadn’t been through the pressure cooker of “Beatlemania?”

The partnership is further complicated by the very different skill sets that John and Paul brought to the table. Neither of them had formal training, but Paul had intensive informal training. He came from a musical family that did a lot of singing together around the piano. He talks about it in this interview with Stephen Colbert, starting at 3:17 (the punchline is at 4:54.)

John’s mother Julia taught him banjo, played him Elvis records, and bought him a guitar. However, he had limited contact with her, and she died when he was young. He was raised by his aunt, who disapproved of his musical ambitions, so he was mostly a feral autodidact. He also had non-musical creative interests, including acting and drawing.

If I had to grossly oversimplify their roles, I would say that Paul is the musician, and that John is the artist.

I believe that musical talent is much more a factor of environment than of genetics. As with crime, music is a matter of means, motive, and opportunity. John and Paul had limited means, but not so limited that they couldn’t access instruments or find the time to learn to play them.

Opportunity is beyond anyone’s control; the conditions that the Beatles found themselves in were world-historically unique.

How about motivation? Is that within a person’s control? John and Paul weren’t born as brilliant songwriters; they got there through years of focused and dedicated practice. What drove them to put in the effort? John talks about having been driven by wanting to make money, but there are many better ways to do that than through music. You could point to the fact that John and Paul both lost their mothers when they were young, but plenty of people lose their mothers without becoming creative visionaries.

Ultimately, it’s a mystery. But I do want to communicate to my students that creativity isn’t limited to people who were “blessed” by circumstances. You can decide that you want to be good at something, and to the extent that you have the time and the resources, you can devote them to getting better. And you can follow good examples like “If I Fell.”

Play Your Heart Out!

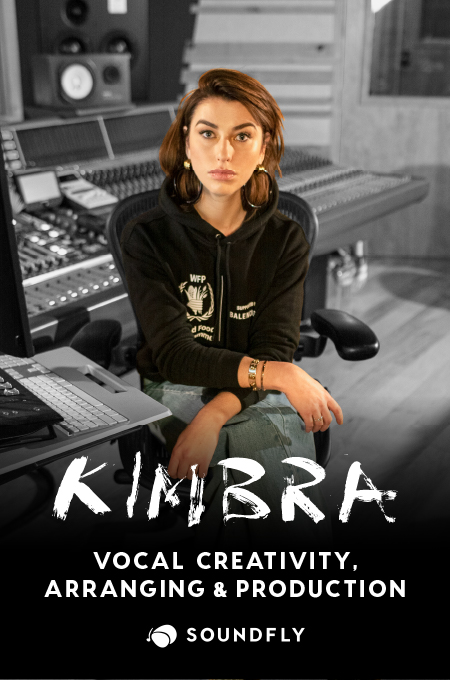

Continue your learning adventure on Soundfly with modern, creative courses on songwriting, mixing, production, composing, synths, beats, and more by artists like Kiefer, Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Ryan Lott, RJD2, and our newly launched Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production.