By Lee Dynes

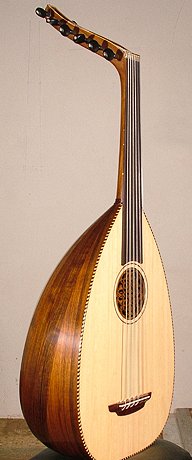

The instrument goes by many names, takes several shapes, and can be played in a number of styles both traditional and modern. The oud or ud, sometimes referred to as barbat in Iran or kaban in Somalia and Sudan, is an instrument predominantly found in the Middle East, Spain, Greece, as well as North and East Africa.

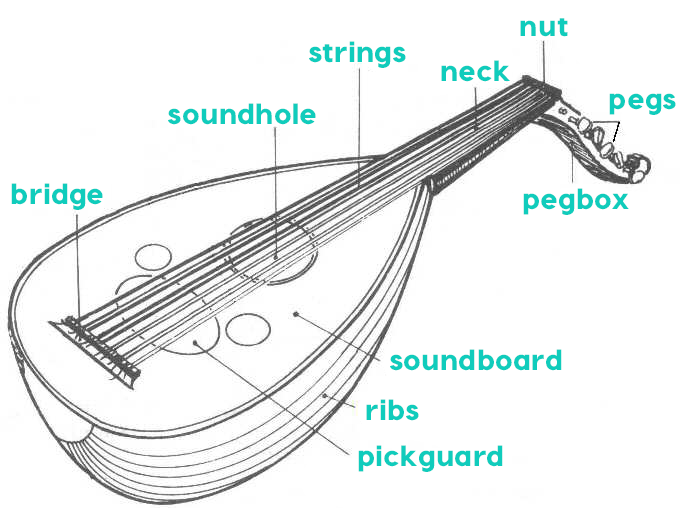

It’s basically a fretless lute, typically with five or six double (coursed) strings. Its three resonating sound holes and short neck help to manifest a sound that evokes scenes of the desert, royal palaces, and smoke-filled cafés.

While many styles are played on the oud, central to almost all of them is the use of the Arabic maqam or the Persian dastgah, scales from the aforementioned regions of the world that utilize quarter tones and microtones. There at least 40-50 maqam or dastgah in use today and many different regional variations on each.

The fretless neck of the oud makes it possible to render these microtonal scales with ease. There’s so much freedom and beauty locked inside these tonal systems; once you dive into the world of maqam, you’ll never want to leave. Let’s take a journey to explore this fantastic instrument from the inside out!

A Short History of the Instrument

Abû Tâlib al-Mufaddal of the ninth century said that Lamech, the descendent of Adam and Cain, invented the oud. Others believe Mani, the prophet and founder of Manichaeism, first created it. Other mythical stories of the oud involve the devil luring the “People of David” to trade their instruments for the oud, and others believe the Greek Philosophers developed the instrument. While these stories are interesting, one may only glean that the oud is ancient, and probably one of the world’s oldest surviving instruments.

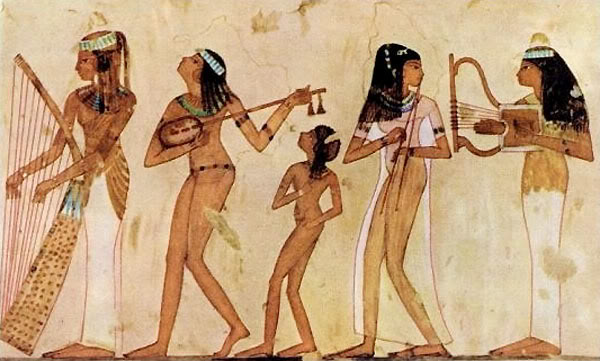

Pictured above, an ancient Egyptian lute, played and depicted throughout Pharaonic times, was a predecessor of the oud. The oldest pictorial record of an oud itself, or a modern lute-type instrument, was dated back to between the first or third centuries. It was probably a veena and originated from India or Central Asia.

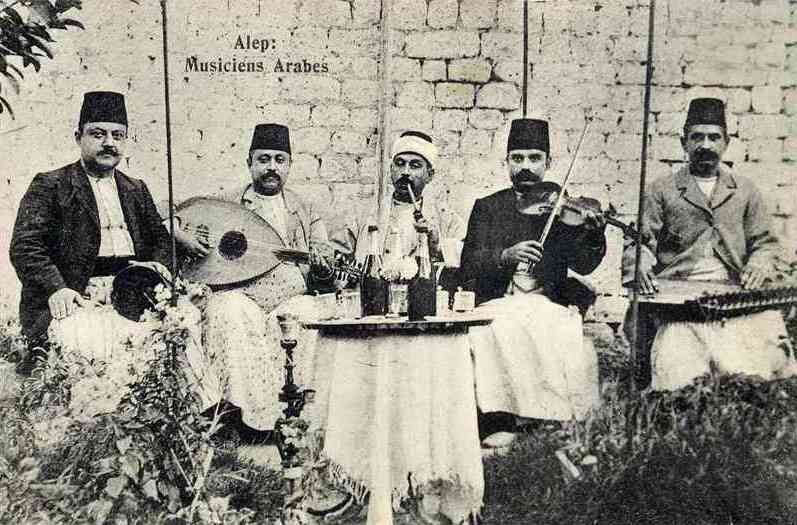

What we do know is that the barbat came first in Pre-Islamic Persia, and later fell out of use during the Safavid period. The Turkic people also had an oud-like fretless instrument called the komuz, which was used in military bands and brought into war. For many centuries, the oud had only four strings, and around the 11th century, an added fifth string created a model closely resembling what we play today.

While the oud has certainly changed over time, its construction has largely remained the same since antiquity: a large, bowl-like body, resonating sound hole, short neck, and sometimes frets. The word “barbat” in Farsi literally translates into “front duck” — when you hold the oud in a profile position with the bowl facing to the right, the head and tuners resemble a duck’s bill with the bowl as its breast.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “6 Powerful Arab Hip-Hop Artists You Need to Hear”

Types of Oud

When purchasing an oud, there are a few things to consider, and it’s easy to get overwhelmed. But fear not! I have already braved this new terrain and will share what I have learned.

There are quite a few different types of ouds, namely Persian, Iraqi, Syrian, Egyptian, Armenian, and Turkish. Thankfully, this can be further grouped into three greater families of Persian, Arabic (which contains the Iraqi, Syrian, and Egyptian styles), or Turkish (similar to the Armenian oud), the most common being Arabic and Turkish.

Arabic and Turkish ouds differ in a lot of ways but most commonly via their size and sound. Arabic ouds are a bit larger with a deeper, darker sound. Arabic ouds are generally tuned lower, giving the Arabic style of playing a heavier, throatier sound than its Turkish counterpart.

Turkish ouds are generally tuned a whole step higher than their Arabic cousins and have a lighter, shriller sound. Also, they’re a bit smaller than Arabic ouds and easier to hold, especially for someone with shorter arms, making them great for learning.

In the Persian family, there are barbats and ouds, which are almost the same save for some differences in shape. The barbat has a more slender body, making it a bit easier to get up the neck. Their sound is slightly sharper than an Arabic oud, even though they’re tuned to the same notes. The Persian oud differs only slightly in its ovular shape and roundness.

+ Learn more on Soundfly: Learn to write for a string ensemble on your own time and with personalized feedback from professional instructors in Soundfly’s Orchestration for Strings course.

Deciding Which Oud is Right for You

Arabic, Turkish, or Persian: how do you decide if you’ve never played the oud before?

Obviously, if you’re beginning a study of a specific regional musical style with its own type of oud, it’s best to learn on the correct instrument with the correct tuning. However, if you’re interested in learning a plethora of styles and experimenting with all kinds of tunings, you should choose a Turkish oud.

And here’s why. You can tune Turkish ouds up or down from the standard Turkish tuning, and they’ll still sound great. Trying to tune an Arabic or Persian oud a whole step up to the Turkish tuning would put too much stress on the neck and strings and make it incredibly hard to play. If you’ve tuned a Turkish oud down to the Arabic tuning, the strings do get floppy, but I’ve met musicians who only play in this way, both for aesthetic and convenience reasons.

If you’re a smaller person, keep in mind that the Arabic ouds can be very large. There are stories of players developing shoulder problems from playing them for too long.

Across the board, due to competition and demand, cheaper ouds produced in Turkey tend to be better quality than cheaper Arabic and Persian ouds. These instruments can get very expensive when they’re ornately designed and intricately handmade, but factory-built instruments tend to favor the Turkish style, which is built to last a bit longer.

That said, the sound of the Arabic oud is much stronger and more resonant and can be a joy to play in its lower tuning.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Three Jazz Artists Harmoniously and Creatively Blending Arabic and Western Music“

Alright, Let’s Talk About Tuning

You’ve ordered your oud online and just received it in the mail (given where they’re typically made, this is often the case). Before playing, you must learn how to tune the instrument. This is no small task!

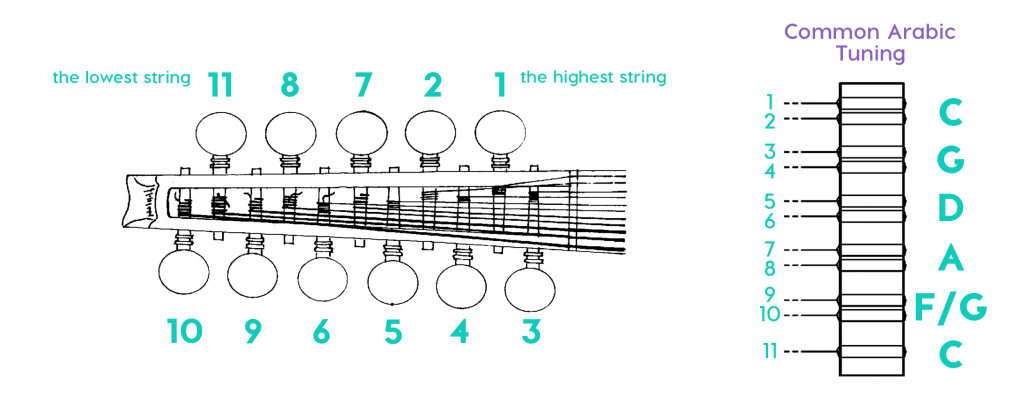

The first time I tried tuning an oud, it took me almost an hour, and I’ve been tuning guitars and basses my entire life! The 11 strings are grouped into two-stringed courses, save for one floating bass string.

That’s not all: the tuning pegs are not as straightforward as they are on guitars and basses. Unlike what’s most common on Western guitars — tuning strings clockwise around the head — the double courses on the oud are tuned in couples back and forth on either side of the headstock like so:

Thankfully, the wonderful internet community has equipped us with apps like the Online Oud Tuner and handy videos such as the one below to help us get the instrument sounding great using the most common Arabic tuning:

+ Learn more on Soundfly: Venture out of standard tuning and start exploring new chord shapes on your guitar with our free course series Alternate Tunings for the Creative Guitarist!

Playing Styles

Phew! Oud tuned. Now, we get to talk about the fun stuff. There are so many different regional styles of playing this instrument varying greatly by country and region, which is understandable considering the widespread cultural use of the oud. I’ll share a consolidated bunch here to shed some light on how these styles may differ.

The Arabic Style

The Arabic style is the most widely practiced style of playing the oud, and it’s played in Arabic tuning, of course. It includes many different forms and genres within its repertoire, such as the samai, which exhibits a 10/8 rhythmic mode followed by a 3/4 or 6/4 rhythm, and the bashraf (Pesrev in Turkish), which throughout the composition only follows one rhythmic pattern, such as: dawr al kabir (28/4), shanbar (24/4), al-fakhitah (20/4), mukhammas (16/4), and darij (93/4). Find out about many more here via Maqam World.

You can hear these songs and scales in the music of Oum Kalthoum, Farid al-Atrash, and folkloric belly dances. Arabic forms of tahmila and dulab, for example, utilize much improvisation over a groove in order to introduce or follow a song passage. They include short melodies called rutts (ruds) in between. Arabic players also play a fast Turkish dance form called a longa.

One of the most immediately noticeable differentiations stemming from the Arabic oud style, as distinguished from Persian and Turkish, is the abundance of tremolo. The Arabic style is generally a more aggressive and loud style with lots of picking, perfect for cutting through loud parties and large string orchestras.

There are so many great Arabic oud players throughout history. Some of my favorites are Simon Shaheen from Palestine; Muhamad Al-Qasabji and Farid al-Atrash of Egypt; Said Chraibi of Morrocco; Abadi Al-Johar of Saudi Arabia; and Munir Bashir, Jamil Bashir, and Naseer Shamma, all from Iraq. I mention them because I strongly suggest you look into the work of these incredible musicians!

The Iraqi style is technically considered Arabic, yet it contains a lot of Persian influence, and the Iraqi maqam vocal tradition can stand on its own as distinct from other Arabic styles. Certainly, there are regional differences within the Arabic style, and if you want to play and learn about that particular method, you’ll want to hear them all.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “What’s the Key to Creating the Tightest Rhythm Section Imaginable? Listen to the Greats!”

The Turkish Style

The Turkish style of playing is highly developed and takes many years to master. While the Arabic style contains a large repertoire of popular and classical songs with vocalists, the Turkish style has hundreds of complex instrumental pieces to draw from. Composers like Cemil Bey and Tatyos Efendi were instrumentalists who composed pieces in the Ottoman classical style of saz semai, making us of the rhythmic form aksak semai usulu (three passages of 10/8 followed by one passage in 6/4). They also composed pesrev, longas (fast pieces), and many other kinds of pieces.

The Turks are known for having very complex rhythms in their music, incorporating time signatures like 2/4, 9/8, and 13/8. The music has a lot of notes to memorize and play and features a complex theorized system of makam.

You’ll find Arab musicians playing semai and pesrev as well, but their interpretations of these pieces sound very different than what’s played by a Turkish-style player. To me, the main difference is the sensitivity of the performer. The Turkish style features a lot of dramatic dynamic shifts, similar to classical guitar. But most noticeably, the Turkish style utilizes left-hand ornaments more consistently than the Arabic style, which has more right-hand acrobatics, and Turkish playing contains subtle differences in sliding.

Once again, there are tons of famous players, but take a listen to Yurdal Tokcan and Yorgo Bacanos in particular.

The Persian Style

The barbat fell out of use during the Safavid Dynasty in Iran, yet it remained a part of the country’s identity. It has recently returned to cultural prominence, although it’s still difficult to find Persian oud playing today, as Arabic and Turkish styles are more dominant and widespread.

The collection of songs and melodic figures that make up Persian classical music is called Radif, and it’s most commonly played on instruments such as the santur, tar, and setar. Oud players often take techniques and music meant for tar and setar and adapt them to the oud. This results in a lot of left-hand flicking, similar to the use of ornaments in Turkish tanbur and oud playing.

Persian playing is also pretty quiet and meditative compared to the Arabic style. You can detect the slow stillness reminiscent of Mongolian and Chinese musical influences. The study of Radif is an arduous task for any newcomer, as players need to memorize around 30 melodies in each “dastgah” (scale). This practice is similar to the studies of the ragas in India and Afghanistan, where it’s said to take over a decade to truly learn how to properly play a raga.

I studied the Persian style for a year, became overwhelmed, and had to stop, but I’m so glad that I was exposed to this beautiful art form. I will definitely return one day to study the intricacies of the Radif. Some great Persian barbat players are Hossein Behroozinia, Arman Sigarchi, Mohammed Eghbal, and Mansour Nariman, who reintroduced the oud to Iran.

The Somali and Sudanese Styles, and Taarab of Tanzania and East Africa

The Somali and Sudanese oud players have, by far, the most “African” sounding style. As the Afro-Arab musical genre of Taarab made its way down the east coast of the continent, the sounds of maqam and the takht ensemble evolved and developed a more localized identity. Also, most noticeably, Somali and Sudanese styles of playing incorporate the pentatonic scale pretty heavily. Most of the oud music is used to accompany voice and percussion in Africa. You can certainly hear similarities to styles like American blues, Indian classical, and even Chinese traditional music.

Some African players who I personally enjoy are Omar Dhuule of Somalia and Mustafa al-Sunni of Sudan in addition to compilation recordings of Taraab music from Tanzania and Kenya.

—

Lee Dynes is a professional oud player, guitarist, composer, and music educator. He currently resides in the San Francisco Bay Area where he teaches at Marin Music Center in Novato, CA. At a young age, Dynes began studying jazz guitar and has studied Hindustani classical music, Middle Eastern music, the folk music of America, Ireland, and Scotland, as well as the music of West Africa, and the Caribbean. Dynes has spent the last six years teaching music at elementary, high school, and college levels, and just independently released an album of original music called Pathways.

Lee Dynes is a professional oud player, guitarist, composer, and music educator. He currently resides in the San Francisco Bay Area where he teaches at Marin Music Center in Novato, CA. At a young age, Dynes began studying jazz guitar and has studied Hindustani classical music, Middle Eastern music, the folk music of America, Ireland, and Scotland, as well as the music of West Africa, and the Caribbean. Dynes has spent the last six years teaching music at elementary, high school, and college levels, and just independently released an album of original music called Pathways.