+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

“… The saxophone has always reminded me of a slimy, pink worm.” – Igor Stravinsky

I bet you could rattle off the names of iconic jazz saxophonists without even thinking too much: John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Art Pepper, Stan Getz… yeah, yeah, yeah… we’d be here all day. And I’ll wager you’d quickly recognize sax solos integral to the success of hit songs from the Boss’s “Born in the USA” to Lady Gaga’s “The Edge of Glory,” and Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street” to Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.”

The death of famed E Street Band saxophonist Clarence Clemons likely made national news in your hometown just like it did in mine.

But if I asked who your favorite classical saxophonist was, I reckon you’d struggle.

While alto and tenor saxophones are virtually synonymous with jazz and regularly featured in contemporary pop, the saxophone has taken on almost outsider status in the classical milieu, with its proponents scrambling to stitch enough work together to either make a living or fend off boredom.

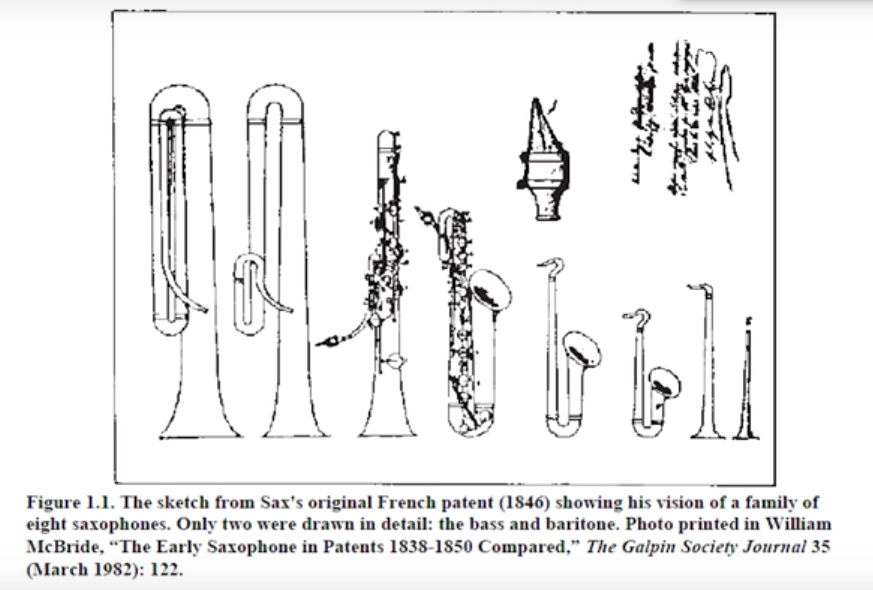

It can certainly be said that the saxophone arrived late to the symphonic orchestration party. Belgian musician Adolphe Sax didn’t even invent it until the 1840s and, by that time, the instruments of the classical orchestra were all but cemented in place. But there were other complications.

Sax’s original invention was made out of wood, not brass. But after several modifications, the instrument would be presented to the French military (Sax was living and working in Paris at the time), and pitched as an instrument with an exciting mix of volume, range, and the ability to play rapid passages. In small part, he succeeded, and early saxophones, now being made from brass, were used in military bands around France and Belgium.

But Sax never made good on the commercial opportunity. He spent much of the rest of his life embroiled in costly, time-consuming lawsuits, putting up with tons of other inventors’ competitive additions to his flimsy patents. Effectively pushed out of the market he himself created, Sax died in abject poverty, with friends petitioning the French Minister of Fine Arts for assistance.

Over in the United States in the 1870s, saxophones started to be manufactured in Indiana and quickly took on with military bands. By the turn of the century, “dance bands” playing ragtime and big band music had further popularized the instrument in North America.

Leading up to the “Roaring ’20s,” the saxophone found its way into jazz ensembles around the nation and became the life of the party! The instrument was such a centerpiece of the new and booming jazz sound, it shed its identity as a tool for fanfare and was considered vulgar rather than versatile in classical circles. Considering jazz’s roots as a predominantly African American style of music, there’s a very racist sentiment at play here that doesn’t need to be over-explained, but which may cut right to the heart of the question at hand.

To make matters worse, certain bands, like Six Brown Brothers, started using the instrument to underscore the comical aspects of slapstick performance art and theatrical routines. This has never officially stopped, by the way, as purposefully comedic compositions such as “Yakety Sax” and the theme music to The Benny Hill Show reveal. And, er, other comedic narratives…

But, by the 1930s, European virtuosi Sigurd Rasher and Marcel Mule were challenging that comedic or raucous reputation with performances of Sergei Prokofiev’s suite from Lieutenant Kijé (1934), Maurice Ravel’s 1922 re-orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Paul Hindemith’s Symphony in B-flat for Band (1951) and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (1941), among other pieces.

Both Mule and Rasher went on to become deeply influential, for generations of both orchestral saxophonists and composers who sought to find new ways to integrate the instrument.

In a chicken-and-egg composer-performer feedback loop, the classical saxophone repertoire slowly built through the second half of the 20th century, but players still tended to be contractors, or full-time clarinetists who doubled on sax when required. The concept of the “full-time classical saxophonist” remained elusive and in a role of occasionally-featured soloists rather than integral orchestral chairs.

Only in the last 15-20 years have we seen a slow but steady sea change, marked by several features.

Firstly, more education equivalency: You can now get your music degree up to doctoral level in classical saxophone studies, from more than one conservatory. Secondly, the superstar effect: What Yo-Yo Ma did for the cello and James Galway for flute, musicians like Jess Gillam and Amy Dickson are doing for classical saxophone. Thirdly, the sleeper cell effect: An increase in grassroots study with events, like the NZ Classical Saxophone Retreat, are making it possible for devotees to skill up in every shade of sax from morning to night, and the saxophone family can live in peace in all genres!

Indeed, even outside of classical circles, the saxophone is seeing a resurgence in music across all genres in a big way.

Indie pop groups frequently feature brass now, drawing from nu-jazz and funk influences and aiming to achieve a more “epic” sound. EDM and hip-hop productions are sampling the saxophone perhaps too frequently (it has almost become a meme of itself). And new contemporary composers are writing tons of music to include brass instruments both alongside string instruments and, heck, sometimes all on their own!

So, Adolphe can perhaps rest peacefully in his Belgian coffin — things are turning up!

Want to get all of Soundfly’s premium online courses for a low monthly cost?

Subscribe to get unlimited access to all of our course content, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.