+ This week on Flypaper, we’re exclusively featuring content that covers music initiatives and recordings from prison, in our editorial series, Behind the Bars: A Week Dedicated to Music In, About, and From Prisons. Follow along via this tag or sign up for Soundfly’s mailing list to stay informed about all of our online learning programs.

By Nathan Salsburg,

curator of the digital Alan Lomax Archive

The following is a full episode of the audio podcast, Been All Around This World, which explores the life’s work of folklorist and documentarian Alan Lomax, hosted by Nathan Salsburg. This episode dives into an important field trip taken by Lomax and his assistant Shirley Collins in 1959 to record prison work songs and other pieces sung by prison inmates at the infamous Parchman Farm, and we’ll explore the deeper contexts of prisoner songs in the American South as well. You’ll hear and read about other trips by Alan’s father John and others to Parchman Farm between 1933 and 1969.

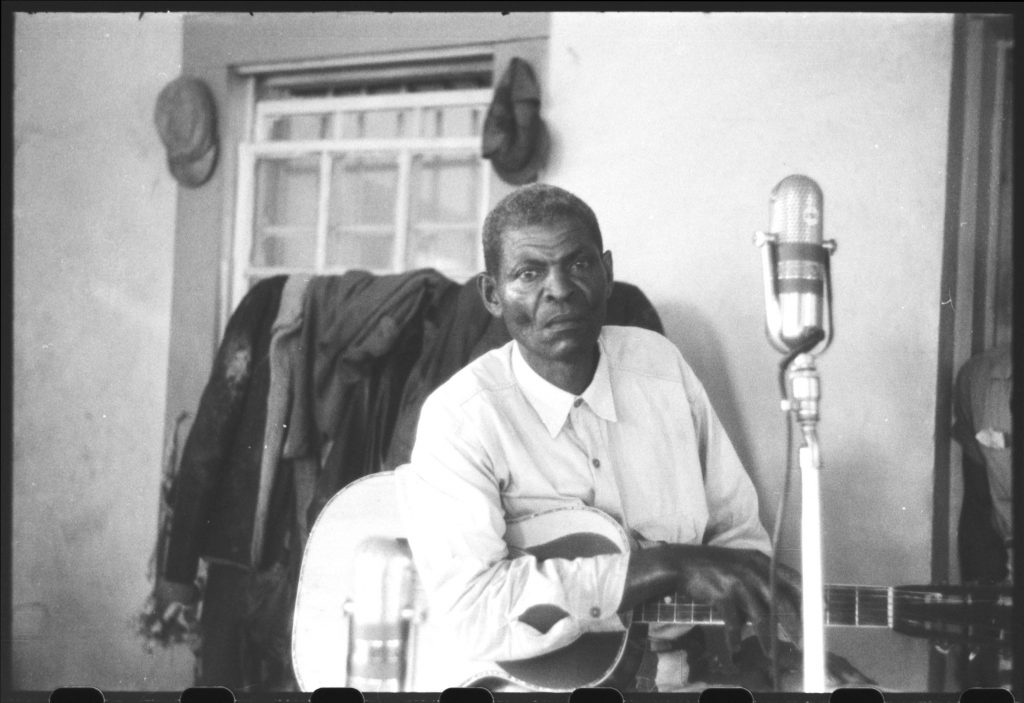

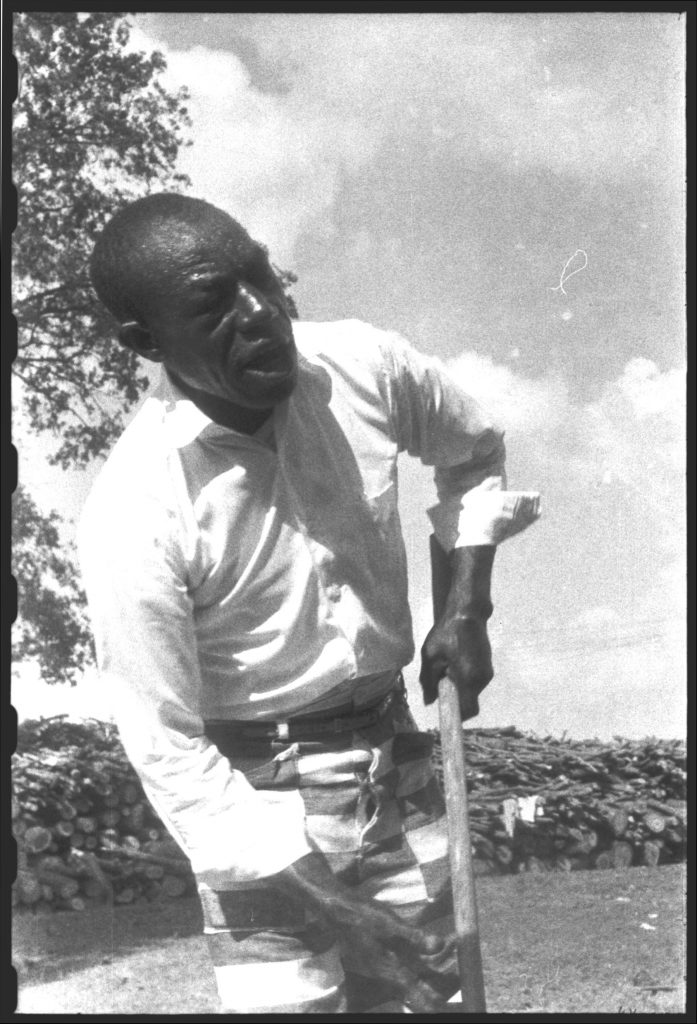

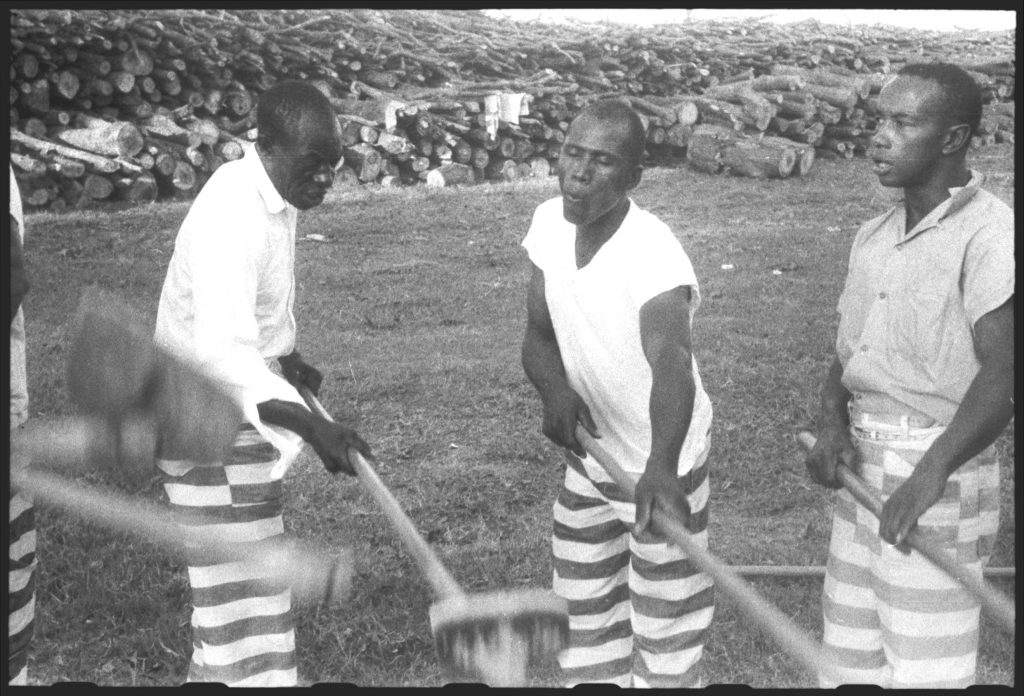

Below is a text transcription of the podcast, with some edits, and a collection of photos taken by Lomax at Parchman Farm in 1933.

Please consider donating to the Association for Cultural Equity, who allowed us access to their vast archive to be able to post these audio recordings and photos.

The Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman Farm was arguably the most infamously backward and brutal of all the Southern prison-plantations, all of which were, by their very nature, backward and brutal. The Lomaxes made recordings at many of them, for reasons we’ll discuss, but Parchman comes up far more often than any of the others. This is in part due to the notoreity of the place, and it’s also due to the fact that Parchman has had some famous musical alumni — from Son House and Bukka White to Mose Allison and even Elvis’s daddy Vernon Presley.

For those already familiar with the black work-songs of the Southern pens, you’re likely most familiar with those recorded at Parchman, where the Lomaxes, between them, visited and recorded five times between 1933 and 1959.

(Angola in Louisiana is another famous prison farm, perhaps best known for its rodeo, and for music fans, it being the site of the first recordings of Lead Belly and later of Robert Pete Williams.)

As I said, I started to tackle this episode this past fall, as it was on the Southern Journey trip when Alan made the last of his Parchman recordings — notable for being the first recordings done of the group work songs in stereo. But travel and reticence got in the way, and I kicked it down the road till now, moved into some kind of response (however impotent) by the continuing news reports out of Mississippi about Parchman prisoner suicides, murders, or otherwise dead by unidentified causes.

If you’ve not been paying attention, and God knows there’s plenty dispiriting news to distract you these days, the short of it is that prisoners are being killed and conditions are spiralling out of control in the Mississippi Department of Corrections: Some 12 inmates have died in the system since the year began; nine of these were at Parchman. There’s an unmanaged if not unmanageable gang problem at Parchman and elsewhere, and many prisoners have used contraband cell phones to send distress calls and texts to the outside, afraid for their lives. But those phones have also documented the grotesque living conditions of the place, from dead rodents to mold to blocked plumbing to meals unfit for human consumption.

State government can say what it likes, and the Mississippi’s new governor is talking plenty, but it’s the vaunted virtue of so-called “conservative leadership” behind the budget cuts and acute staff shortages that’s this time pushed Parchman to the limit. And like the federal class-action brought against Parchman in 1971, Gates vs. Collier, which successfully argued that the prison had long engaged in “cruel and unusual punishment,” and forced a federal reorganization in 1974, a new lawsuit has been filed claiming the same.

You might have heard about this due to the support given to the prisoner-plaintiffs by Jay-Z and Yo Gotti, or seen the reports in The New York Times and other national outlets. Fundamentally, though, Parchman is what Parchman’s always been, and there are now many calls from many quarters about finally shutting the place down for once and for all.

Well. Now you see why I was dragging my feet about putting this episode together.

Our focus here will be on the recordings made by four men — John A. Lomax, Herbert Halpert, Alan Lomax, and Bill Ferris — at Parchman Farm between 1933 and 1969. This was the old Parchman; a Parchman that was, quite simply, a plantation in the antebellum mold with slave labor performed by prisoners. In the place of the old master was the warden, or more accurately, the State of Mississippi itself, who profited off of a forced-labor pool consistently supplied by a legal and penal system constructed almost exclusively with the priority of perpetuating white supremacy.

A Mississippi-sized middle-finger to the failed attempts made during Reconstruction to enfranchise and legitimize Black citizenship.

John Lomax, in his search for the Black folk song he considered “the least contaminated by white influence or by modern Negro jazz,” found that the Southern penitentiary system provided what he called “our best field.”

In the eleven Southern state pens, Lomax assumed (rightly) that he would find that the group work songs of the Black South, fast disappearing in the free world, would have been preserved in the strictly segregated world of the prisons, where Black and white prisoners — and of course, in the land of Jim Crow, there were far more of the former — worked, ate, slept, worshipped, and recreated separately.

Parchman wasn’t the first prison that John Lomax, with 18-year-old Alan in tow, would visit on their first field trip in the summer of 1933, but it would prove to be the most fecund one. Between 1933 and 1939, John Lomax would record nearly 250 songs from Parchman inmates, male and female; and not just the group work songs and field hollers, but also game songs, blues, ballads, toasts, and many sacred performances.

+ Read more on Flypaper: Check out our full week of content on music in, about, and from prisons here.

His first attempts at capturing the work songs, however, failed miserably, as the instantaneous disc-cutting machine was hopelessly inadequate to capture the voices of some 100 men along what was called “the line” — the long line of inmates inching forward as one, their hundred some voices singing at their work, whether clearing ground with hoes, chopping wood with axes, or picking cotton and dragging sacks behind them.

Instead, John set up with small groups or individual performers during their noontime break — thus, the Lomaxes were never able to record the actual line, and instead the records they made are of re-enactments of the work and the singing.

Jail House Bound is a collection of pieces from the first session held by the Lomaxes at Parchman in August 1933 (issued on CD by WVU Press). Here’s a piece by an unidentified group of prisoners referred to as “He Never Said a Mumbling Word.”

John A. Lomax made return visits to Parchman in the springs of 1936 and 1937, during which time he made two of my favorite recordings to come out of the place. They’re not work songs, but no less powerful.

The first is a performance of the Reconstruction-era anthem “Oh Freedom,” a song that would later become identified with the Civil Rights Movement. It’s sung by group of women led by M.B. Barnes at the Parchman women’s camp. The other singers are Louella Dade, Passion Buckner, Alberta Turner, Bertha Riley, Lily Mallard, Christine Shannon, and Josephine Douglas, and I say their names because every opportunity we have to reaffirm their individuality and humanity is a corrective, however tardy and minuscule, to the system that created and sustained Parchman and, may I say, still sustains it.

Also because when John Lomax made those 1933 recordings at the prison, he only took down some of the singers names — and in fact none of the women he recorded in the Parchman sewing room. Thankfully, come ‘36, he thought better of it. John Lomax (not unsurprisingly) was unfamiliar with the song and identified it in his notes as “No More Trouble.” Let’s hear it:

It was during these sessions that he recorded the second of which, and what is one of the most powerful and enduring performances he ever managed.

Little is known about Big Charlie Butler, and much of what is is owed to researcher Stephen Wade, whose book, The Beautiful Music All Around Us, devotes a chapter to Charlie and his “Diamond Joe.” Take a listen:

+ Read more on Flypaper: “JoogSzn on Recording Drakeo The Ruler Over the Phone from Jail”

Butler was 40 years old at the time of this recording, his first of the song (he’d make two more), and was one year into a ten-year sentence for attempted murder with an axe. This was his second ten-year bit at Parchman for the same crime. He had been a resident of Tunica, Mississippi; his escape from the county farm there had landed him again at the state pen.

Alan Lomax attempted to contact Butler in 1943 for his permission to issue this recording in what became the Library of Congress’ Afro-American Blues and Game Songs album, but Lomax’s letter was returned unopened with the inscription “gone free left no address.” Butler had been pardoned six months earlier.

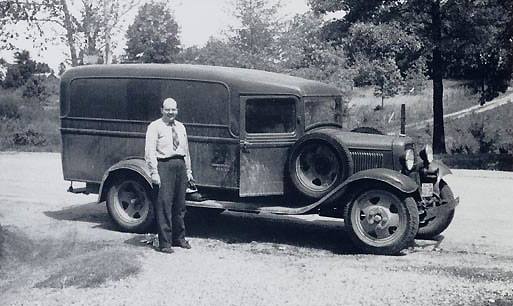

I have to say I don’t have a sense of what Herbert Halpert’s draw to Parchman was. By the mid-’30s he was an experienced folklorist and documentarian who’d been working with the Federal Theater Workshop in New York City, and roving out into the Catskills, the Poconos, and the Jersey Pines to do folk-song and story-collecting. He visited Parchman Farm in 1939 with Abbott Ferriss, director of the Federal Writers Project in Mississippi, on part of a longer recording trip through the state the two were conducting in a converted ambulance they called their “sound wagon.”

What set Halpert’s recordings apart from those John Lomax had done, or those Alan Lomax would do, was that Halpert spent a considerable amount of time in the women’s camp, recording not just spirituals (as John had done the same year) but game songs, work songs and lyrics they’d composed themselves.

Perhaps Halpert’s greatest meeting was with a singer called Mattie May Thomas, who’d had experience with imprisonment since at least 1925, when she had done time in the Shelby Co. Workhouse in Memphis. Thomas performed for Halpert a song she said she’d learned an outline of from her time in Nashville, but that she’d fleshed out with her own ideas. Some of the images, and turns of phrase occurring in this piece are simply astonishing.

Alan Lomax made his first solo visit to Parchman in November 1947, eager to use his new Magnacord tape-recording machine — the first truly portable machine on the market — which he knew would provide an improved document of the power of the work songs. He returned the following February in what seemed to be a tribute to his father, who had died of a heart attack just a week and a half earlier during a visit to Greenville, Mississippi.

The recordings Alan that made over these two visits were issued in an LP in 1958 called Negro Prison Songs — it was the first introduction the vast majority of its listeners had ever had to this music, starkly presented with a simple impressionistic rendering of a big house composed entirely of prison bars on its cover. “These songs,” Alan wrote in the liner notes to that record, “coming out of the filthy darkness of the pen, touched with exquisite musicality, are a testament to the love of truth and beauty which is a universal human trait.”

Here’s one of the most well-known of Lomax’s late ‘40s recordings from Parchman, led by Benny Will Richardson (called 22) and a group of men with hoes, titled “It Makes A Long Time Man Feel Bad:”

I’m referring in this program to the group work-songs by the titles given them by their singers or the recordists. These titles are often the first lines, and were typically how they were cataloged and/or published. But it’s worth saying that a work-song wasn’t a discrete composition, sung the same way every time, but was instead strung together from a collective cache of floating lyrics that, in form more than content, applied to the particular condition, time, and, as Woody Guthrie would call it, “job of work.”

That’s not to say that they’re always completely improvised. Songs like “Rosie,” or “Stewball” or “Take This Hammer,” or at least the recordings that were made of them, have a thematic integrity that persisted not just across several decades in the various camps at Parchman, but in other camps of other prison farms in other states. Remember that one song, as we imagine it, could have gone on for hours; a good song leader was someone who could sustain them in the heat, under a blazing sun, for as long as was required.

And different tasks had different rhythms, so a song that accompanied flat-weeding with a hoe might not be brought to bear on log-cutting with an axe. The rhythms, and the necessity of the prisoners maintaining them as one, were essential to their safety. They kept someone from braining their neighbor with an axe, say, but more essentially, they maintained a regularity of movement across the line, so no one prisoner could be singled out for punishment for not working hard enough.

For a much more cogent, detailed, and beautifully wrought consideration of the work-songs, I can’t recommend the work of folklorist and prison documentarian Bruce Jackson enough. His Wake Up Dead Man, a book of and about work-songs in the Texas Department of Corrections, is a masterpiece, and that’s saying nothing about his many recordings made in Texas pens.

No one can or should mourn the passing of the Black work songs of the Southern penitentiaries, sustained as they were in conditions of abject brutality, racism, and exploitation. Even by Lomax’s visit to Parchman in the late ‘40s, he found the custom of work-song singing was dying out; older singers were dying or losing their voices; some of the younger prisoners were less inclined to sing what they saw as anachronistic hold-overs from an even more atavistic period.

Modernizing tendencies came late to Mississippi and God knows much later to Parchman, but they couldn’t be kept out altogether. Lomax’s last trip to the prison was in 1959, and the irony of that visit, was that although he had a state of the art Ampex stereo tape machine to finally record the work-songs in their full range, the tradition had diminished considerably over the intervening years, and it was rapidly going extinct.

Here’s one of those stereo recordings made in 1959 at Parchman — a tremendously beautiful, quartet rendition of a song called “I’m Going Home,” composed by its leader, one Ervin Webb. You’ll hear him explain its origins following the singing.

The singing of a work song that riffs on the theme of old Tom Devil. Led by a gifted singer named Johnny Lee Moore, who was joined by Ed Lewis, along with Henry Mason and a prisoner named James Carter. You know Carter from his having led the singing of a version of “Poor Lazarus,” also recorded by Alan Lomax during this ‘59 visit, that ultimately appeared on the soundtrack to O Brother Where Art Thou.

To make a rather long story short: In 2002, James Carter was flown on his first-ever flight to that year’s Grammy Awards with his wife and three daughters, where that album won Best Album of the Year. When he was located in a Chicago hospital a week earlier, he had had no recollection of making the recording, much less any idea it was on a multi-million-selling soundtrack album. He was presented with a $20,000 check and, as the story goes, at the Grammy after-party, was approached by Emmylou Harris who told him she liked his singing.

He replied, “thanks hon, I’ll have another drink.”

The Mississippi-born filmmaker, recordist, writer, professor and general cultural advocate William Ferris, was the last person to make recordings at Parchman. He visited in 1969 and again in 1974 — the tapes from this latter session, tracks for the film he was shooting at the time — testify to the obsolescence of the songs, as on them you can hear older prisoners coaching younger or newer ones how to hold and drop their axes, and how the lyrics went, for the sake of re-creation for the camera.

You can find the edited films on Folkstreams.net as well as on a DVD issued by Dust to Digital. Also released by Dust to Digital is the extensive and very beautiful set Voices of Mississippi, compiling an assortment of Ferris’ Southern field recordings, photographs, and moving images.

The last song we’ll hear on the program this week is from Ferris’ 1969 Parchman recordings, identified as “Water Boy Drowned in Mobile Bay.”

For a full playlist of the songs in this episode, click here.

Alan Lomax (1915-2002) was the foremost folklorist of the 20th century. Over seven decades he traveled throughout America and the world, documenting the traditional songs, tunes, and dances of hundreds of locales, from thousands of people. He made the first recordings of now-legendary figures like Lead Belly, Honeyboy Edwards, Bessie Jones, Woody Guthrie, Muddy Waters, and Mississippi Fred McDowell, but he was most concerned with giving a voice to the regular folks who might have never been heard otherwise. He called this “cultural equity.” Lomax’s influence on popular music can’t be overstated. “Without Alan Lomax,” Brian Eno said, “it’s possible that there would have been no blues explosion, no R&B movement, no Beatles and no Stones, and no Velvet Underground.”

Improve all aspects of your music with Soundfly!

Subscribe to get unlimited access to our premium online courses, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.

—

Nathan Salsburg is curator of the digital Alan Lomax Archive at the Association for Cultural Equity, the non-profit research center and advocacy organization Lomax founded in 1983.