+ This excerpted lesson is presented courtesy of Kiefer’s in-depth course on Soundfly, Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats. Sign up and learn to bridge the worlds of theory, improvisation, and jazzy hip-hop, and improve your piano chops.

Understanding how a note relates to the chord that accompanies it can be really helpful when developing and pairing harmony and melody. In Kiefer’s course, he touches on this across various sections while talking about chord voicings, but let’s expand on it here with some simple observations about various chord tones and tensions and how to use them.

Roots

For Kiefer, a root in the melody against a major seventh chord isn’t “the most graceful” note choice. This is largely because of the clash created by having the root in the melody and the major seventh in the accompanying chord, just a half step beneath it. The note in the melody is the focal point and the way that seventh rubs against it messes with its clarity.

When melodies in jazz standards end on the root of a chord, you’ll often see a Maj6 chord in place of a Maj7, because that slight change eliminates the conflict.

Here’s an example from the end of the melody of “Body and Soul.” In John Coltrane’s version below, you can hear it at 0:39 when the pianist McCoy Tyner finally breaks the tense harmonies he’s playing and lands on a big resolution, no major sevens in sight.

Of course, there are certainly other scenarios where roots work really well.

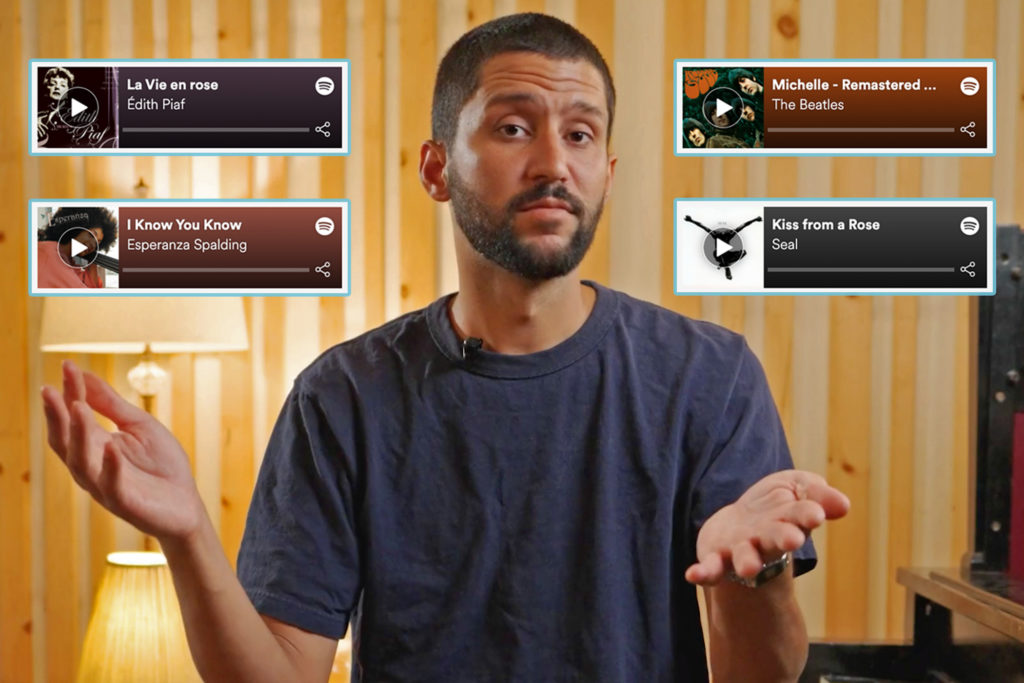

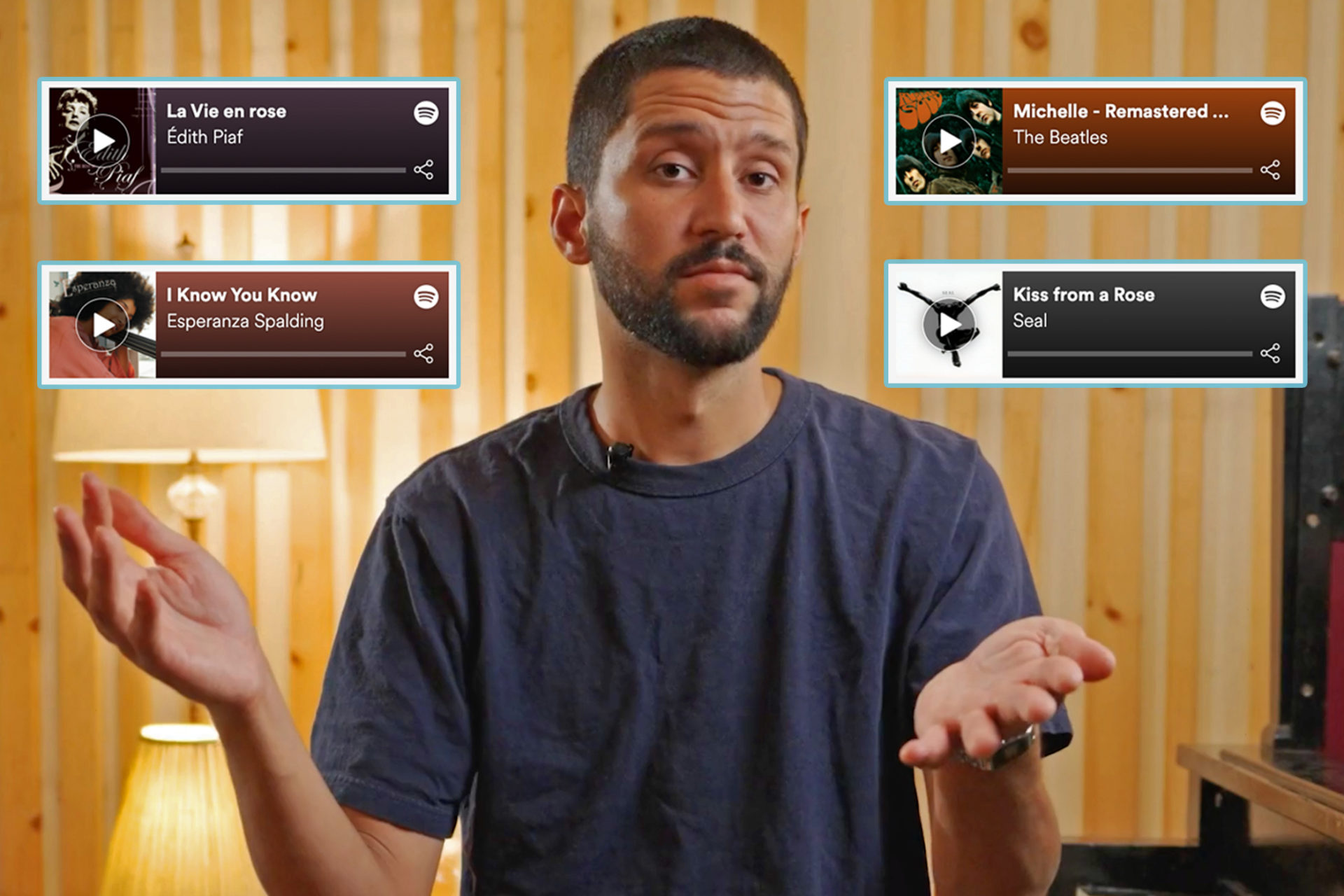

Check out to this example from the beginning of the melody of Édith Piaf’s “La vie en rose:”

When to Use Roots: Roots can sound fine within the context of a chord voicing, but may not work as well on top of major seventh chords. That said, they work fine as melody notes against minor sevenths, dominant sevenths, diminished sevenths, and minor seven (flat five) chords. They can also provide a really nice, colorful sound against sus chords.

Ninths

Kiefer loves the sound of a nine in the melody over a major seventh chord, partly because they’re so “non-committal.” A ninth can work with multiple chord qualities, so it doesn’t carry the same kind of harmonic implications that other tensions might.

Take a listen to the opening melody from Arthur Hamilton’s “Cry Me a River.” The example can be heard at about 0:25 in the recording below, which features a beautiful performance by Ella Fitzgerald.

When to Use Ninths: Ninths sound great in so many situations. Use them pretty much anywhere and you should be fine. If a ninth is giving you trouble within a voicing, try making sure it’s above the third, which may mean bumping it up an octave.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “A Pop Songwriter’s Introduction to Jazz Chords.”

Flat Nines and Sharp Nines

The flat nine and sharp nine have very specific sounds. Both are pretty tense, so the choice to use either is usually made with real intention.

If you’re newer to these tensions and would like to give one a go, consider following it with something close and more resolved. For instance, if you have a flat nine in your melody, try following it with the root of the chord. If you have a sharp nine, try moving up a half step to the third of the chord.

Here’s an example from the end of the melody in Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “Água De Beber.” You can hear it around 0:52 in the recording below.

And check out the sharp nine in this melodic excerpt from Esperanza Spalding’s “I Know You Know.” The example corresponds with the lyrics: “You already know but I’ll sing it again” at about 0:46.

When to Use Flat Nines and Sharp Nines: While they’re not exactly interchangeable, sharp nines generally work wherever flat nines do, though we’d guess you’ll run into the latter far more often. In some cases, they even sound good together.

Both notes can add lots of interest to dominant seventh chords, especially when added to secondary dominants, because they take us just a little further away from the original key. Over major or dominant chords, they can create a really nice, bluesy sound.

Thirds (Major or Minor)

Depending on the quality of the chord in question, you’ll have either a major or minor third at your disposal. These notes are pretty important, because they’re the ones that tell us the most about the quality of the chord.

Here’s an example from a different genre: Seal’s 1994 pop hit “Kiss From a Rose.” You can hear this melodic figure right out of the gate.

When to Use Thirds: Use these as often as you’d like! They tend to sound pretty interesting and since they’re chord tones, they shouldn’t create any major conflicts.

Elevenths

Over major chords, elevenths can be chaotic and unstable. Over minor chords, they’re beautiful. Here’s an example from Chick Corea’s “Spain.” Notice how he lands on a beautiful eleventh at 1:17 when the whole band comes in.

When to Use Elevenths: These are best reserved for minor chords, where they can add beauty and ambiguity without conflict.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “How D’Angelo Uses Funky Dominant Sevenths in ‘Sugah Daddy.’”

Sharp Elevenths

Generally, you’ll probably want to steer clear of elevenths on major seventh and even dominant chords, but there’s a great alternative: the sharp eleventh. Sitting a tritone above the root of the chord, the sharp eleventh sets up an expectation for the fifth of the chord, adding tension and gravity without muddying the sound of the major third.

When to Use Sharp Elevenths: These will give you a bright, Lydian sound. Whimsical and not quite resolved, they can be added to major seventh and dominant chords to provide some character.

Fifths

Like the ninth, the fifth is a fairly non-committal note choice, as it doesn’t imply much about the quality of a chord. In the context of a purely diatonic situation, it isn’t always the most interesting choice, but its openness and versatility make it an excellent selection in pieces that call for more flexibility.

Take a look at all the highlighted fifths in this example from “Sir Duke” that starts around 0:37. Stevie Wonder’s vocal melody is replete with fifths, which makes sense given there are a lot of chord changes here and he doesn’t want things to sound muddy.

When to Use Fifths: The fifth will almost never get in the way of other notes, so it’s a solid, grounded default. It’s pleasant, reliable, and easy for the ear to pick out. Use it as often as you’d like, but consider balancing it out with notes that provide a little more character.

Thirteenth

The thirteenth can add a lot of lushness to a dominant chord. When the thirteen and flat seven are played right next to each other, they can be very tense and dissonant, but if you move it above that note, it really open things up.

Here’s an example from Bill Evans’ “Beautiful Love.” You can hear it around 0:18, or try playing the line below on your own.

When to Use Thirteenths: Thirteenths often sound great on dominant chords, especially if you’re using ninths as well. They can also work on major seventh chords and minor seventh chords (especially when using a Dorian scale) — although there’s a risk of making your harmony too muddy in these instances.

Flat Thirteenth

Much like the flat nine and sharp nine, the flat thirteen has a specific and unique sound, and can definitely sound like a momentary departure from the key.

Here’s an example from the melody of Thelonious Monk’s “Straight No Chaser” at about 0:10 seconds in:

When to Use Flat Thirteenths: The flat thirteen works particularly well on a dominant chord where you’re embracing a lot of dissonance in your sound. It can imply a different scale, like a whole tone scale or altered scale. You’ll often see it played along with flat or sharp nines.

Sevenths (Major or Minor)

Much like the third, major and minor sevenths contribute to the overall character of the chord, and can thus be really interesting melodic choices.

Here’s a beautiful example of a flat seven played over a B♭-7 chord from the Beatles’ hit, “Michelle.” It’s the note that falls on “belle” after the phrase “Michelle, ma belle.”

When to Use Sevenths: If there’s a major seven in the chord, it’s a safe bet that it’s in the melody as well. In fact, it can even be an easy alternative to the root if that was your first instinct and things are clashing. Minor sevenths can be even more forgiving, so don’t hesitate to use them in your melodies.

Harmonize a single note in many different ways.

There’s a lot to process here, but getting comfortable with this sort of thing is mostly a matter of time and experience. With that in mind, here’s an activity we recommend:

- Pick a note (any note) and play it in your right hand.

- Now, with your left hand, play every chord you can think of in which the note you selected is the root — major triad, minor triad, sus chord, dominant seventh with a flat ninth, and so on.

- When you’ve done that, move onto chords in which the note you chose is the minor third.

- Then, move onto chords in which it’s the major third, then the fifth, then the ninth, and so on.

You can also do this activity in a more casual way by just picking one or two roles at a time. For instance, you might see how many chords you can think of in which C is the major or minor seventh.

The important thing is that you try to stay engaged as you complete the activity. You may find it helpful to move back and forth between two chords a few times, or to audibly say things like “C is the minor seventh in a D minor 7 chord.” After a while, it will start to feel like second nature and you can approach the exercise more effortlessly.

Let us know what you come up with! If you’re already a Soundfly subscriber, you can feel free to share your work in either the #works-in-progress or #kiefer channels in Slack.

Don’t stop here!

Keep learning about theory and harmony, composing and arranging, songwriting, improvising, and so much more in Soundfly’s exciting new course with Grammy-winning pianist and producer, Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.