“A composer is somebody who changes the sonic situation… I see composition as basically just a change, because we have to admit that sound is going on all the time.” —Michael Pisaro

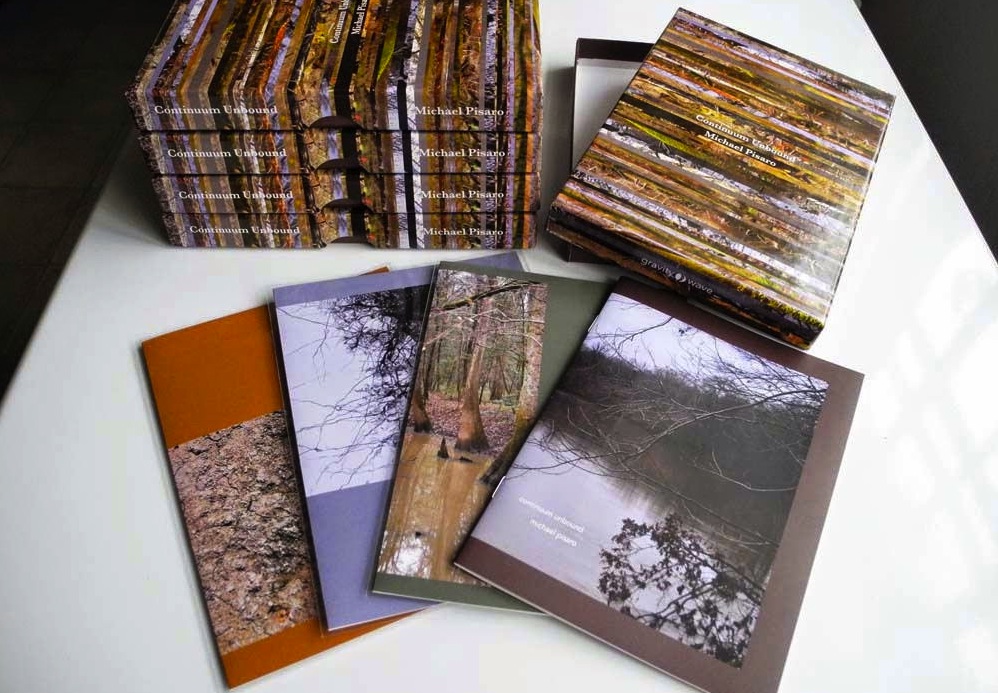

One of the musical pieces that has undisputedly come to define the last year or so of my life is Michael Pisaro’s 3-disc opus Continuum Unbound. This piece is a masterwork in provoking what I would consider a wabi-sabi perception of the audible environment through deep listening, not only on the part of the listener, but also from the composer’s standpoint, as the composer needs to open himself up to an improvisational mindset with naturally-occurring sonic experiences. Pisaro is a prolific guitarist and lecturer at CalArts and a composer in the experimental and fluxus tradition of John Cage, Christian Wolff, Robert Ashley, and George Brecht.

Continuum Unbound is split into three works, each conceptually and sonically informed by the same questions of perspective, and responding to them with organizations of sounds that promote a view of the natural sonic landscape as being seemingly continuous and yet fundamentally fragmented. The pieces ask what is chance, how do we recognize it, and categorize it; and asks us to evaluate whether patches of sound and silence are continuous or discontinuous sound.

All three works are exactly 72 minutes, and so the whole piece unfolds over 3.5 hours. The first work, Kingsnake Grey, is a field recording documenting one entire sundown in Congaree National Park in South Carolina. This recording sets the space for examining continuity and contingency in nature as we are allowed the privilege to decipher all the subtle changes and tiny auditory moments that make up this event. Next is Congaree Nomads, which is a linear composition derived from nonlinear sonic events, specifically 24 three-minute field recordings, and overlaid with instrumental “fogs” of harmony. The third and final chapter, Anabasis, features no field recordings and is instead notated in 72 parts for five musicians.

—

How special is Continuum Unbound for you?

I feel it was like a summation of the things that had concerned me over the past decade: field recording (starting with Transparent City); massed orchestration (which includes a large group of collaborations with Greg Stuart); and indeterminacy and contingency as they operate in music (and music scores) — which goes way back, but started to take a new form in the “harmony series.” It’s been interesting since then to see what I can now leave behind to think about new directions. Also, I think I learned a lot about collaboration in the series of discs that came out on Erstwhile (with Taku Sugimoto, Toshiya Tsunoda, Antoine Beuger, and Graham Lambkin).

The pieces that make up Continuum Unbound are said to explore the notion of continuity and contingency of not only naturally occurring sonic events, but sound in general. How did you work to create this theme throughout the pieces?

It was a few flashes of insight and a slow process of sifting. Having come to know the Congaree National Park in South Carolina in the previous year, I had a chance to plan several ideas for the composition beforehand. But the depth of the sundown recording experience made me reconsider everything. It was a constant process of measuring the concept against the sound and vice versa — with the one continually finding ways to transform the other. Some part of it was conscious, but a lot of it was visceral, intuitive.

I think that therefore “listening” really covers a lot of the work. Listening carefully to what we are recording in the situation, listening to the individual sounds Greg made as they came together, listening to everyone’s contributions to Anabasis. But there’s a point (which many improvisers know) where listening turns to action (or non-action): decision. That’s usually the most frightening and satisfying part of the work for me.

Does Continuum Unbound exist in a series of works that explore similar subject matter?

There’s a long history of an interest in both things (continuity and contingency) in my work. I think it dates all the way back to the work with just intonation and microtonality that I began in the 1980s, while studying with Ben Johnston. This is where the potential continuity of pitch space really struck me. And you can’t raise the question of continuity without thinking about discontinuity. I view contingency as something that has grown out of the successive interests in chance, silence and indeterminacy. It’s like the next extension of that field — and the ability to label, and more importantly think about it grows out of a long period of contact with the work of Deleuze, Badiou and more recently, Quentin Meillassoux.

In terms of series: The “Grey” series deals with noise and fog (disc 1, Kingsnake Grey is one of that series). The large ensemble pieces with Greg Stuart, like A Wave and Waves and Hearing Metal 2 prefigure Congaree Nomads. And Anabasis has given birth to a new series (there are two more of those now).

Would you say that this piece was derivative of a listen-first mentality?

Not quite. There is some listen-first, but I think listening is shaped by what we’ve done, what we’ve experienced. So maybe it would be more accurate to say that I’m trying as much as possible to listen in a direct way, but I need to prepare the ground for that. In fact I believe listening and composition (in the broadest sense) are so tightly intertwined that one may never know which comes first.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Pauline Oliveros Made Me a Better Listener”

How do you think your methods for composing music differ from traditional music writing?

More and more I think compositional traditions don’t really exist. We formulate our ancestors. So, if I, for example, choose Ockeghem (especially Missa Mi-mi), the Bach of the Musical Offering, the Goldberg Variations and the Art of the Fugue, Schoenberg (at the point of transition to atonality), Cage (and Wolff and Lucier), the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the furthest reaches of punk (Gang of Four, X-Ray Spex, The Raincoats, Wire, Pylon, Sleater-Kinney) as my “tradition” I can make a case for the organic development of my “methods.” Anyway, it’s very hard to stand outside myself far enough to really answer that question!

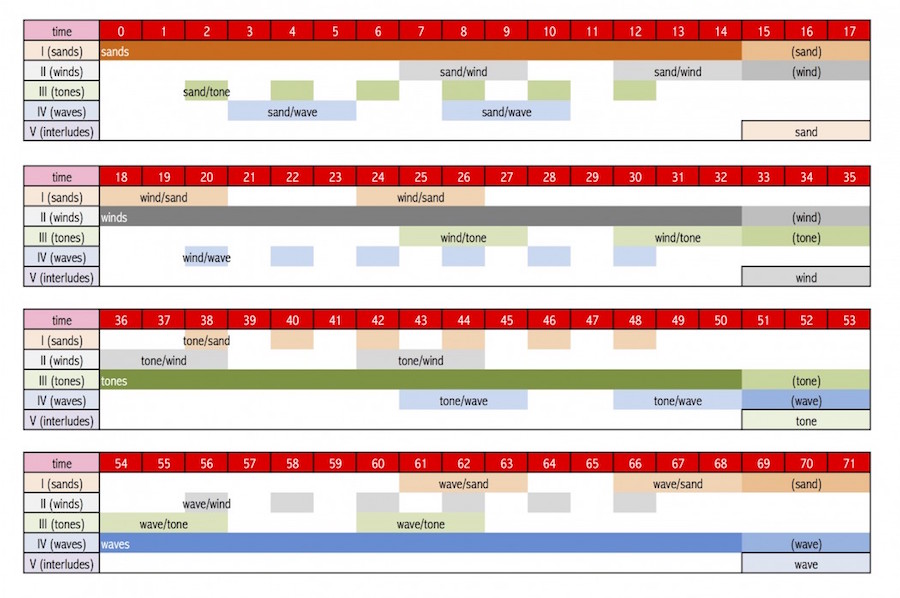

Anabasis is based on the materials “sands, winds, tones, and waves.” I get that these are natural elements, and I assume it’s a way of using tonal, textural elements to mimic nature, but why these relationships?

They grow out of the story told by Xenophon in the Anabasis, and then also the poem by St. John Perse. It was a way of finding a material relation to the concept. It was like saying the Anabasis occurs in an environment and is conditioned by it. Of course I also knew that for my collaborators these would suggest rich ways of finding sound. (And each one — Greg, Patrick, Joe, and Toshiya went way beyond what I could have expected.)

Is it possible for others to perform this work with other instrumental voices to represent those materials?

Absolutely! There’s a very real score with openings for any five people who want to take it on.

Congaree Nomads, on the other hand, is written for these “instrumental fogs” to be created by you and Greg Stuart. I love that term, and it immediately brings to mind Ingram Marshall’s Fog Tropes. Can you talk about where this came from, and what purpose this playing tactic serves?

The fogs are collections of tones and ways of playing them. Of course, like all my music with Greg, it is absolutely shaped by his way of working. He took the score and made a full-fledged version (choosing the instruments, making the recordings and mixing them). This track (which is actually a combination of 48 separate tracks) is what we used to mix with the 24 field recordings.

“Fog” though is both a) something we encountered in a very direct and unforgettable way after one evening of field recording in the Congaree and b) a philosophical/theoretical concept that has become important for me. The fog we saw in South Carolina is the most vivid I’ve ever encountered: like an intense grey light at ground level. A diffusion so dense that one was more “in fog” than in the world. I began to think that fog had for me an ontological significance as well — as a way of being in the world (and attempting, usually unsuccessfully) to find clarity there.

What life do you think this piece has beyond the expectations that you brought to it initially?

That’s not for me to say. I will say that the response to it was beyond what I expected. I thought it might be too large for most listeners, though I clearly underestimated the patience of a significant group of them! I am very curious to see if people make other versions of the scores at some point.

How did you get into teaching ?

When I began doctoral study at Northwestern in the early ‘80s I thought I wanted to teach college. However, exposure to the routine and especially, the apparently frustrated lives of my teachers convinced me it was not necessarily the best life for a composer of “unpopular” music. I had the feeling that most of my teachers were deeply disappointed that they hadn’t “made it” and therefore had to teach to make a living. Thus upon finishing I really thought I would never do it. After a few years out of school, I was asked to teach some courses at Northwestern and discovered that, actually, I loved doing it. Teaching needed for me no other justification than that it seemed to help people if one cared about it. All on its own, separate from my artistic ambitions, it seemed like a good job. Luckily I was good at it, and it was a time (unlike now) when there were enough good jobs that one had a reasonable hope of securing one, as did in fact happen. After about 30 years I find I still love the job — and have the great luxury of teaching at a place where I can design everything I teach — remake it on a year-to-year basis — and have really wonderful, surprising students (at CalArts).

Michael Pisaro’s new record with legendary composer/pianist Christian Wolff, Looking Around, comes out next week via Erstwhile. Please take the time to watch Pisaro talk about teaching at CalArts and his music in this great interview by Artists House Music.