+ Soundfly’s Intro to Scoring for Film & TV is a full-throttle plunge into the compositional practices and techniques used throughout the industry, and your guide for breaking into it. Preview for free today!

There would be only a handful of musical pieces that could rival Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” for its iconic status in screen music. It was present in the starting days of silent cinema when chosen by D.W. Griffith to partially score his controversial, artistic watershed, Birth of a Nation (1915), and it was lovingly parodied by Chuck Jones in Looney Tunes’ What’s Opera, Doc? (1957).

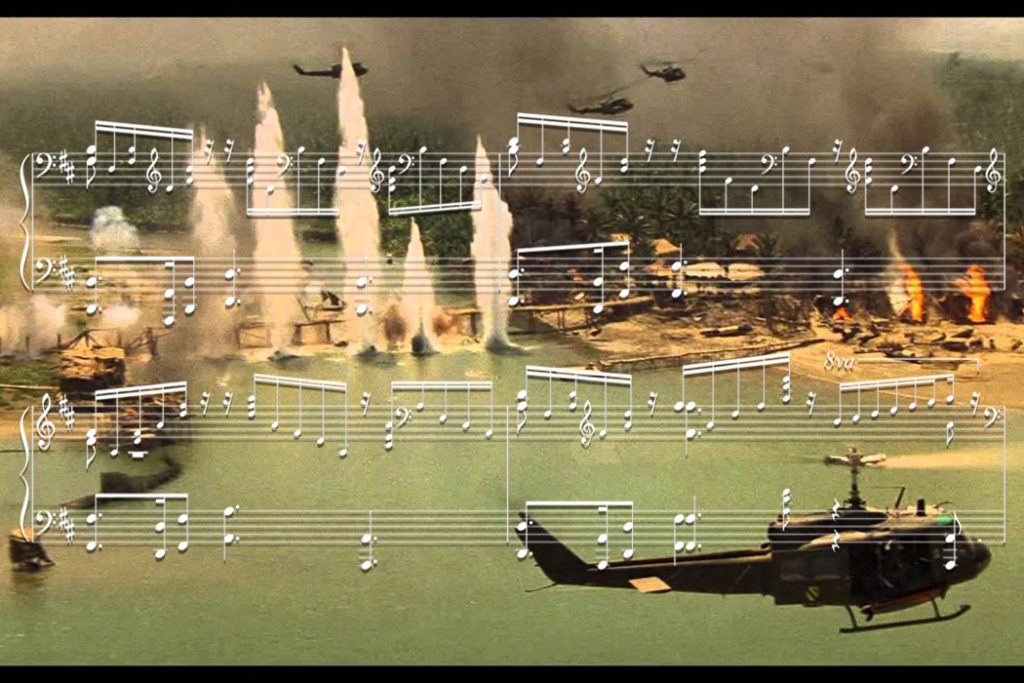

Yet when director Francis Ford Coppola and his sound editor Walter Murch dropped the needle on “Valkyries” for 1978’s classic Apocalypse Now, it was undoubtedly the moment the piece became etched in the collective consciousness of filmgoers. Wagner’s epic, soaring music finds good company in films with similarly immersive intentions. Hearing that martial horn refrain, both ominous and triumphant, is likely going to return viewers to the overwhelming and wanton destruction of a North Vietnamese village. Looking at this pairing closely, we can unpack what makes a successful film cue — thematically, visually, and financially.

But first, if you haven’t seen the Apocalypse Now sequence yet, strap yourself in.

By way of historical context, the original leitmotif appears as “Walkürenritt” in the third act of Wagner’s 1870 opera Die Walküre. The opera revolves around Valkyries, mythic figures in Norse mythology who take half of the warriors slain in battle to Valhalla, a celebratory hall of the afterlife where they will prepare for the final apocalyptic battle, Ragnarok.

Coppola’s scene opens both literally, and figuratively, by pressing play on the tape, thus commencing the tense trills and fast, high-register scalar runs of the “Walkürenritt” theme. In the air, chopper crews load weapons and mentally prepare for battle — the music tells the viewer to prepare as well. It’s not long until we hear the famous ascending melodic motif, based upon triads in the B minor scale. This was originally used by Wagner to illustrate the majesty of a heavenward ascent. However, it appears in the film as an ominous precursor of destruction, “death from above,” a battle cry that will only be heard by the unsuspecting Vietnamese villagers when it’s already too late.

This is only the first of many ways that the triumphant musicality of the piece is reimagined as a sardonic commentary on the actual bloodshed of these events. The repetitive upward motion of the motif ends up emphasizing the ever-heightening intensity of the assault on “Charlie’s Point,” and the ever-advancing onslaught moving deeper into the jungle and the body count rises.

Towards the end of the scene, at 3:52 in the above video, Coppola signals the nearing end of this mission as he sends a helicopter through black smoke, only to emerge in bright blue skies cued up to Wagner’s triumphant resolution to a choral B Major. This synergy of sound and image offers a temporary respite from the tumultuous battle, the music implies peaceful closure yet the audience knows full well that there’s more horror to come.

“Valkyries” is particularly effective as film music not just because of its compositional features, but also because of the role it plays within the movie’s own world. It finds its way into the universe of Apocalypse Now through the character of Sgt. Kilgore, played by Robert Duvall. He’s made a habit of cranking Wagner from attack helicopter loudspeakers before, saying:

“We’ll come in low, out of the rising sun and about a mile out we’ll put on the music… My boys love it!”

Kilgore’s choice of music illustrates the ruthlessness of war, symbolized by a man that will go to any lengths to psychologically break the enemy and harden his own men for the horror and danger of battle. To Kilgore, this is “hype” music. Music that exists within the world of a film is called diagetic, and the fact that it originates through plot and character, as the piece is originally heard first by the soldiers in the film helps the audience buy in to this choice of music. Non-diagetic music, on the other hand, is background music that we can hear, but the characters can’t hear themselves.

But “Valkyries” is ultimately both diagetic and non-diagetic.

Though introduced into the fray through the unconventional tactics of Kilgore, Coppola and Murch hold the volume high, keeping the music at the forefront of the scene. It transcends the world of the film and enters the world of the on-looker. It becomes it’s own character, and alters the time of this scene in a way that the movie world has no control over.

Thus, the music here serves two distinct purposes for us as viewers: firstly, to allow us to witness this event through the eyes and experience of Kilgore himself, and secondly, to allow us to witness this event as reassembled artistically, dramatically, like it has been set in a theatre (indeed, the “theater of war”) and orchestrated accordingly. This complex duality inevitably provokes questions to us viewers directly, like:

“What do you see here? Are you feeling a weird mixture of horror and exhilaration? What does this make you feel about war, and humans generally?”

Film music in general doesn’t just reflect the action on the screen, it offers hints at commentary on it. It provides a framework for the viewer to understand the significance of the events and opens our perspective up to include an alternate, perhaps moral or emotional take.

To take another example from this very same scene, there’s a moment where the music drops away entirely (at 1:18 in the above video). We’re left with images of villagers looking apprehensively at the sky, the only sound accompanying their lived reality is the gentle ambience of the jungle. What perhaps begins to inspire their fear isn’t the music, it’s the almost imperceptible Earth rumbling beneath their feet as the choppers approach from ten miles out. Then we hear the blades, and only then does the music start to fade in.

This bizarre eye of calm in the ensuing storm gives us a brief moment to contemplate whether what is going on is ultimately right or just, or whether we’ll even be able to witness the following events from the villagers’ perspectives at all.

It’s this emotional, visceral feeling that explains why “Valkyries” and Apocalypse Now are such a potent pairing and why for many it’s hard to hear the music without running the scene in one’s head. It’s important to know that musical choices in great films are rarely accidents. As Walter Murch explains himself:

“The ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ was so deeply associated with the attack on Charlie’s Point, and had been for so long — from birth, so to speak — that we who were working on the film, editing the picture and mixing the sound, could barely conceive of separating the two. How that particular Solti recording came to be chosen, I never found out — the decision predated my joining the film — but there is a general consensus in musical circles that Solti’s interpretation, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic [sic], has never been surpassed.”

Decca, however, initially declined the production any right to reproduce Georg Solti’s 1965 Vienna Philharmonic recording for the film. So important was the synergy between that recording and the film edit in progress that Murch spent countless hours combing through other albums of the same piece. He came up empty-handed, only to be saved at the 11th hour by Solti granting his personal permission for use of his recording in the film. I’m only skimming the surface of Murch’s retelling of this tale, he has some brilliant thoughts on musical rhythm and film rhythm coming together that are well worth reading.

I’m also only scratching the surface of the role music plays in this film, let alone how music is used in film at large to manipulate both our immediate and lasting reactions to what we see occur in front of us. When a film uses a preexisting song or musical work, usually one that already has some widespread cultural familiarity, this is called a needle drop. Was Coppola deliberately referencing this filmmaking tactic by showing us the character pressing play on the open tape reel? I don’t know, but it wouldn’t make much sense for them to use an actual turntable on a helicopter that’s bouncing around and turning in all directions, now does it?

If you want to read a bit more on needle drops in film, here are some excellent places to start your discovery. Want to improve your ability to play with the listener’s expectations and emotional responses to your musical subject matter?

Don’t stop here!

Continue learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Kiefer, and the new Ryan Lott: Designing Sample-Based Instruments.