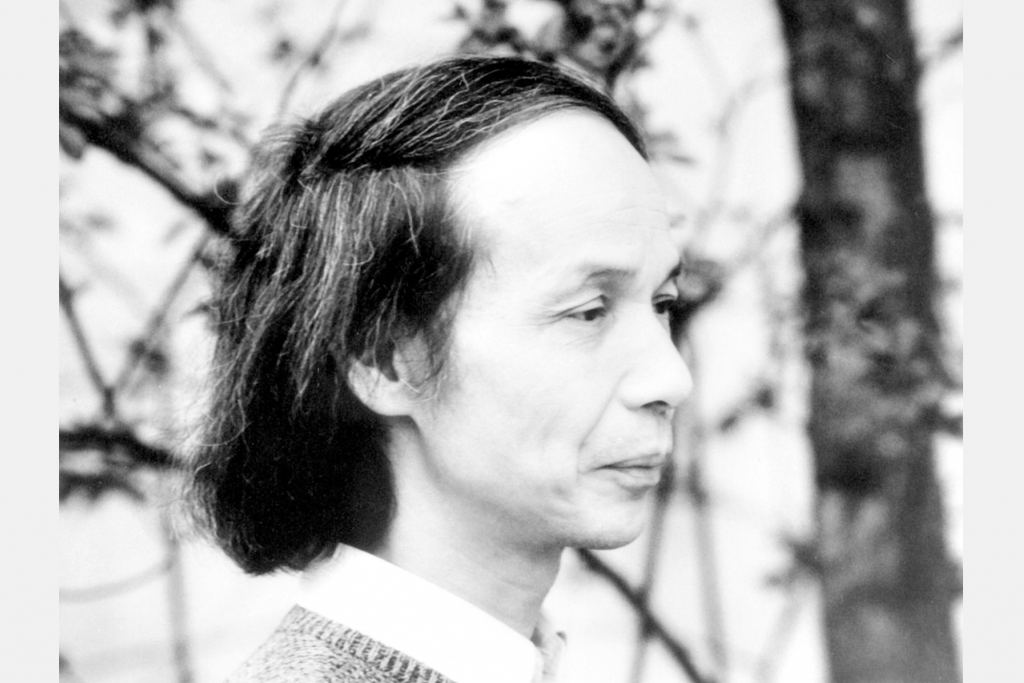

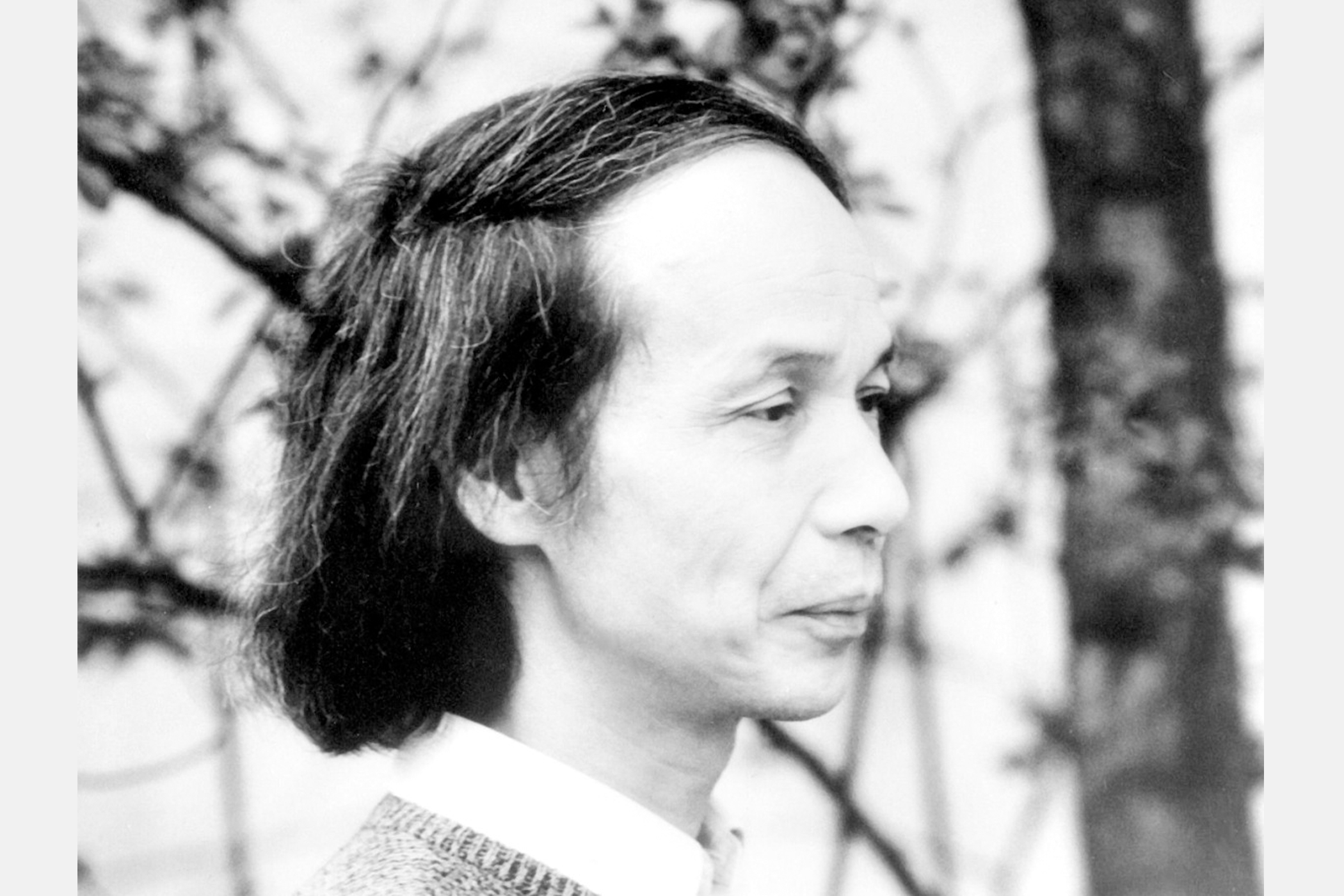

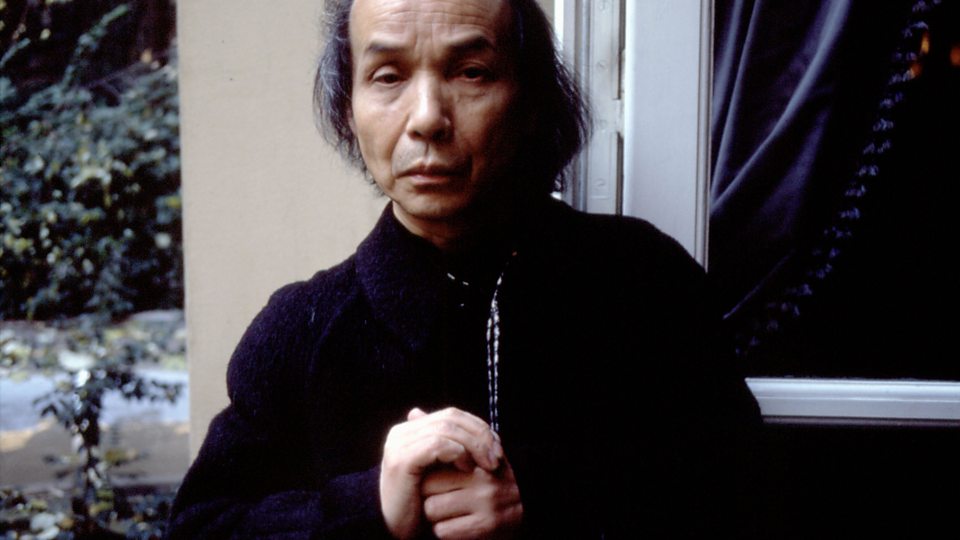

Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996) was arguably the most well-known and influential Japanese composer of the 20th century. In addition to composing prolifically for the orchestra, Takemitsu wrote many chamber works, solo guitar music, electro-acoustic pieces (incorporating the use of magnetic tape loops and found sounds), a number of pieces that feature soloists playing traditional Japanese instruments backed by the orchestra, as well as scores for over 100 films (including Pale Flower, Double Suicide, Harakiri, Woman in the Dunes, and Ran).

Born in Tokyo in 1930, Takemitsu spent his childhood in Dalian, China before moving back to Japan and being conscripted into military service at the age of 14. His time serving in the Japanese national army during the war instilled in him a great sense of bitterness, leading to a subsequent rejection of Japanese tradition. The post-war American occupation of Japan exposed him to radio broadcasts of Western orchestral music which Takemitsu listened to incessantly, and later credited the radio as his first teacher (he was primarily self-taught).

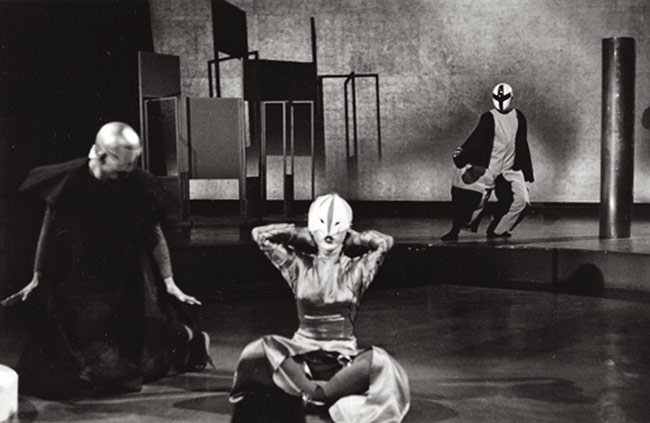

In 1951, Takemitsu acted as a founding member of Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop), an anti-academy, avant-garde group of Japanese artists who collaborated on mixed-media projects with the intention of embracing new technologies, moving away from Japanese artistic tradition, and exposing Japanese audiences to contemporary Western music. Takemitsu’s early music is marked by this rejection of Japanese culture, and one can hear in it the influence of composers such as Messaien, Schoenberg, Wagner, and Debussy.

Japanese government representatives accidentally put on a recording of Takemitsu’s 1957 piece Requiem for Stravinsky during a trip the composer made to Japan. Stravinsky was so impressed by the work that he insisted on letting the piece play out and meeting Takemitsu. This meeting and the praise Stravinsky sang of Takemitsu would prove to be an instrumental moment in exposing the music of Takemitsu to Western audiences, and shortly afterwards he began receiving commissions from some of the leading orchestras in the U.S.

In 1966, he received a commission from the Koussevitsky Foundation for which he composed Dorian Horizon, premiered by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Aaron Copland. A sparse and patient composition, Dorian Horizon creates a varied landscape of soft and harsh textures and gestures occurring intermittently with moments of silence or near silence. In the year following, Takemitsu received a commission from the New York Philharmonic as part of its 125th anniversary celebration. For this occasion he composed November Steps, which features two traditional Japanese instruments, the shakuhachi and the biwa as soloists, backed by the orchestra.

Takemitsu’s musical trajectory is marked by a striking self-guided absorption with Western European orchestral music in his early years, followed by a gradual return to his roots in his experimentation with traditional Japanese instruments and musical styles in later years. He has credited this return in part to John Cage who himself was very much influenced by Zen thought in his own compositional practice:

“I must express my deep and sincere gratitude to John Cage. The reason for this is that in my own life, in my own development, for a long period I struggled to avoid being ‘Japanese,’ to avoid ‘Japanese’ qualities. It was largely through my contact with John Cage that I came to recognize the value of my own tradition.”

In a 2007 article for The New Yorker, Alex Ross points out the circularity of the chain of influence in Takemitsu’s work, “because both Debussy and Cage, in their very different ways, had been heavily affected by Japanese music and Japanese thought. In a sense, Takemitsu was taking back what his tradition had given to the West.”

A key concept in understanding the work of Takemitsu — especially the later work — is the concept of ma, what the composer defined as the “powerful silence.” The embrace of silence and the use of it as a device to create tension and resolution, the recognition of it as something that can keep a piece of music moving forward, is one of the most striking features of Takemitsu’s work. The pieces slowly enter in from silence and gradually return to silence, and can feel at times like long, musical meditations with brief moments of harshness or timbre change peppered throughout.

The following is an introductory “playlist” that aims to demonstrate the arc of Takemitsu’s nearly five decades of active work. Not many examples of his film music are included here, though I highly recommend heading to your local public library or somehow seeking out the incredible films Pale Flower, Harakiri, Woman in the Dunes, Double Suicide, Pitfall and Ran for starters. The way Takemitsu’s music plays off the drama, and informs it with intrigue and uncertainty is pure genius.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “14 of the Most Influential Latin American Composers of the 20th Century”

Static Relief (1956)

This piece was composed using magnetic tape loops.

Requiem (1957)

This piece attracted the attention of Igor Stravinsky, which proved critical in introducing Takemitsu to Western audiences.

Dorian Horizon (1966)

Commissioned by the Koussevitsky Foundation, premiered by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, and conducted by Aaron Copland.

November Steps (1967)

Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic to celebrate its 125th anniversary. In this piece, Takemitsu sought to blend traditional Japanese instruments with the orchestra. He discovered the challenge of this and ultimately they are kept separate and predominantly played in alternation.

Autumn (1973)

For biwa, shakuhachi, and orchestra. Takemitsu continued to experiment with the idea of composing for both Western orchestral instruments and traditional Japanese ones and achieved more of a complete integration of the two in this piece than he did in November Steps.

A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden (1977)

Note the contrasts in volume and the tension of the chord voicings in this piece.

Ran (film) (1985)

One of the late, epic films of Akira Kurosawa with film score by Toru Takemitsu. This is an excellent example of the concept of ma as the beginning of the film features almost exclusively natural sounds as the score. A famous battle scene occurs in which a single gunshot killing a central character shifts the score from the sound of the orchestra to the sounds of battle.

Nostalghia (1987)

This piece was composed as an ode to Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. It is comprised predominantly of slow-moving, muffled, and eerie chords changing underneath a solo violin with moments of textural change appearing (a moment of soft glissandi, double stops, pizzicato, muted tremolo) only to return to those slow, muted chords. Personally, I hear the influences of Prokofiev’s first violin concerto, Mahler, Schoenberg, and Webern, but what makes it decidedly Takemitsu is in the subtlety of variation, the comfort in keeping it at such a slow tempo, the harmonic language, and how wonderfully he captures the patience and haunting imagery of Tarkovsky.

From Me Flows What You Call Time (1990)

And Then I Knew ‘Twas Wind (1992)

Sidenote: Watching these pieces on YouTube demonstrates a sharp contrast between the noise and vacuousness of our modern society with the patience, precision, elegance, and space of Takemitsu’s music. Hope you enjoyed!

—

Sources:

http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/display/jikken-kobo

http://www.onyxclassics.com/reviews.php?CatalogueNumber=ONYX4027

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0006316/

https://www.theguardian.com/music/tomserviceblog/2013/feb/11/contemporary-music-guide-toru-takemitsu

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/02/05/toward-silence

http://www.lardbiscuit.com/jidaigeki/kurosawa-ran.html