+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

Top 40 charts typically aren’t where I go to find new music. When I was a younger musician, I’ll admit I saw that as a sort of badge of honor.

Early in my career as an electric bassist, I was hired to play in a wedding band. Right off the bat, this meant adding thirty or so tunes from Billboard’s holy list to my existing repertoire in about three days’ time. That first gig went pretty well, and with a few hours of having new material under my belt, I figured I was through the thick of it… but no. The coming months saw a stream of strangers’ special days, each of which came with its very own, personalized collection of “Today’s Hits.” For a while there, I was learning tunes in real time (and thanks to some off-the-setlist song requests, there were definitely times when that was happening in a very literal sense). Unsurprisingly, the experience made my ear more accurate and even enhanced my melodic and harmonic vocabularies.

The thing about Top 40 music is that it has to be easily digestible to be successful. Usually, it can’t be anything too complex — simple, singable melodies, accompanied by very logical chord changes. As it turns out, this makes pop a great place to start learning about theory and expand your harmonic knowledge.

When I was first asked to analyze a pop tune, I felt it was my Canadian duty to avoid Justin Bieber’s tune “Sorry” (which a real Canadian would have pronounced “SORE-ee” rather than “SAW-ree”). However, I live with a semi-secret Belieber, so the song was hard to avoid, and it turns out there’s actually something pretty harmonically hip going on under Justin’s dulcet tones.

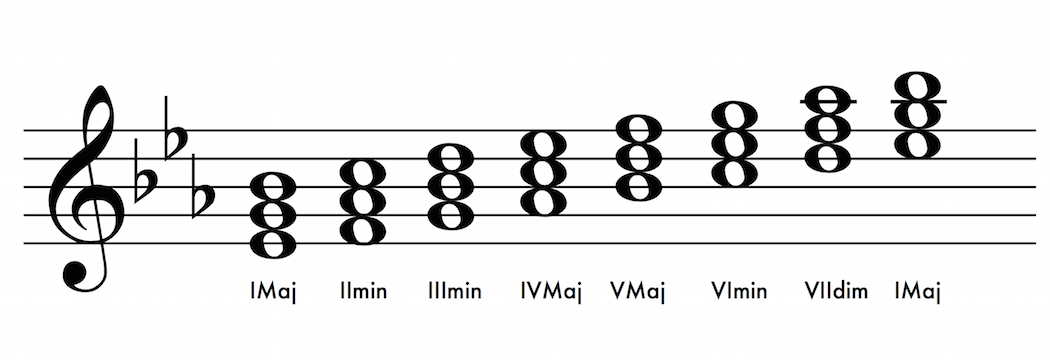

You see, “Sorry” is written in E♭ major (a key that boasts the same number of flats as C minor, more on this later). This means E♭ major is the tonic or “home” chord, thus all of the melodic and harmonic content is being created from the E♭ Ionian (major) scale.

However, throughout the entire song, there isn’t a single E♭ chord. This creates a consistent sense that the song is being pushed forward, because we never land on the safe and comfy resolution our ears expect.

“But Carter, you said E♭ major and C minor share a key signature and there is definitely a C minor chord in this song. Isn’t this song then in C minor?”

No, hypothetical person questioning me, it is not.

It’s totally fair to assume this song is in C minor. Sure, C minor chords shows up here and there, and much of the melodic content could be attributed to the C minor pentatonic scale. I wouldn’t blame anyone for thinking this song is in C minor.

But listen to it, and I mean REALLY listen to it. Does that C minor chord sound like home, or just a temporary passing chord on its way to the dominant? I respect those who feel differently, but my ears practically beg it to go to that E♭ and it doesn’t, which is why I dig it.

Before we move deeper into our analysis of this track, take another good look at the image above. Those are all the diatonic triads built on top of the scale tones of E♭ major. If this is new to you, I strongly suggest playing these chords on your chosen instrument. See if you can hear the relationship between each chord.

How does the B♭ major chord sound after the F minor chord?

Which chord seems to have the strongest need to resolve to that Eb♭ chord? (Hint: It’s the B♭ chord.)

The great thing about studying pop tunes is that they very rarely stray from a given key. They like to keep things rather diatonic. This means that with just a small bit of practice, you can start to recognize these chord progressions for yourself, even without your instrument in hand. We will go much deeper into our understanding of how these chords function in later articles, but for now let’s just get comfortable with what we get from “Sorry.”

The main chord progression of this tune features an A♭ major chord for two beats of the first measure, C minor for the last two beats of that first measure (falls on beat three), and B♭ major for an entire bar, repeating over and over and… over. Using the image above, you can now analyze this progression as IV major, VI minor, and V major.

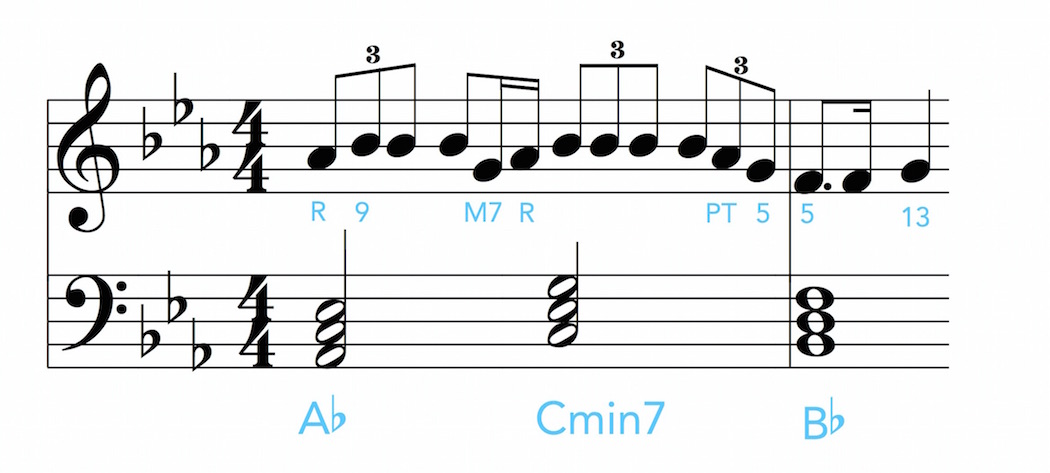

Now take a look at the melodic content of the verses, provided by the luscious voice of our boy Biebs.

We can identify each note as a part of the chord being played under it, and here’s where we see a little more hipness in this song:

The initial triplet figure begins with an A♭ over an A♭ chord. Cool, that’s the root of our chord… but then it’s followed by two B♭s.

The B♭, my friend, is what we call a tension. A tension is not a chord tone (root, 3rd, 5th, or 7th), but it can be used to add color to chord structures.

In this case, the B♭ is the 9th, even though it looks like it should be called the 2nd. Tensions get bumped up an octave (2nd becomes 9th, 4th becomes 11th, and 6 becomes 13th).

Over our C minor chord, we get a triplet figure of all B♭s, making the chord a C minor 7. This is followed by the use of a passing tone (Ab) to get from the 7th to the 5th. Finally, over the B♭, we have an F (the fifth of the chord), moving to a G (the 13th, another tension).

If all this talk on tensions is a little overwhelming, relax. I’ll dig deeper into them in the next article and show how they can be used to create some beautiful melodic content. For now, perhaps the most important lesson is that there is something to be learned musically from every artist, even perpetually teenaged Canadians.

Want to get all of Soundfly’s premium online courses for a low monthly cost?

Subscribe to get unlimited access to all of our course content, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.