On Friday, Katy Perry and NBC launched an anthem you’ll likely be hearing throughout the rest of the summer. Her new tune, “Rise,” is designed to accompany NBC’s coverage of the Rio Olympics, but is apparently a project the pop singer has been working on for some time. In her own words, “Rise” is “a song that’s been brewing inside me for years, that has finally come to the surface.” Having Max Martin, arguably the most prolific songwriter and producer in history, on your team is one sure fire way to bring a musical idea to fruition. But does the song reach the Olympic heights it’s striving for?

Perry’s penchant for empowering songwriting (“Roar” and “Part of Me” being among the best examples) makes her ideally suited for an inspiring Olympic anthem, and at first listen, “Rise” has all the components you’d expect from an motivational power ballad: uplifting lyrics, strong cadences, and electronic support. However, a closer look at the musical characteristics of “Rise” can shed light on the song’s strengths and weaknesses and offer some helpful lessons for composers and arrangers. First, let’s hear the song!

Form

“Rise” follows a basic pop form. After a count-off, Perry sings a verse-prechorus-chorus structure twice, extending the final chorus to end the tune. There’s not much to say about this basic structure, but it’s worth noting that a simple, consistent form lends an aura of stability to the composition as a whole, even more than a rondo or theme and variations would. Indeed, the lack of an introduction and use of prechorus material to end the song adds so much stability to the piece that it borders on stagnation.

Both Martin and Perry use prechoruses consistently, but not exclusively. Indeed, Martin’s use of prechoruses in pop dates to his time producing and writing for boy bands in the late ’90s.*NSYNC’s “Tearin’ Up My Heart” uses one, as does The Weeknd’s more recent “Can’t Feel My Face.”

Perry uses a prechorus in “Teenage Dream” (also produced by Martin). What’s notable, however, is that Perry’s two most obviously motivational hits (“Roar” and “Part of Me”) do not in fact use them. Considering Martin’s consistent use of prechoruses over his decades worth of production credits, and given the simple nature of “Rise” as a whole, it may be that Martin encouraged Perry to include one.

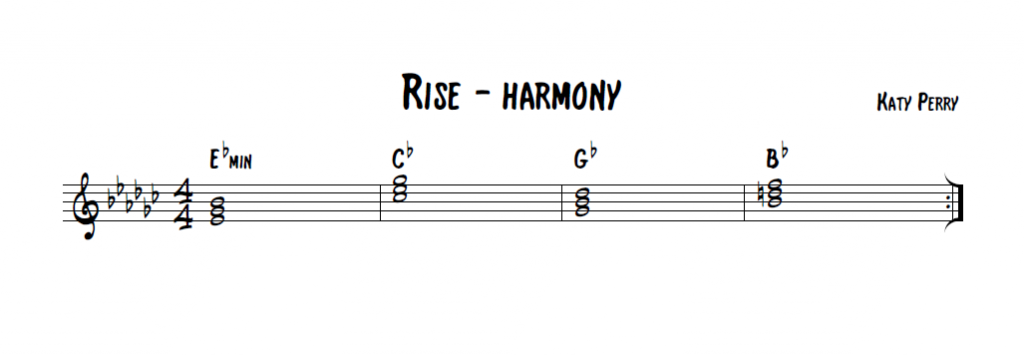

Harmony

The entirety of “Rise” uses the same harmonic progression of four triads, each lasting one whole measure: E♭ minor – C♭ – G♭ – B♭. Ending each four bar phrase with B♭ firmly anchors the piece in E♭ minor. Using a minor key for a motivational ballad seems counterintuitive. Typically, such pieces seek to be uplifting, and we commonly associate major tonalities with majesty and triumph. However, Perry avoids the negative connotations of her minor key by filling three out of every four measures with major chords. In fact, using a minor tonality brings a sense of apprehension to the piece as a whole, building mystery and tension for listeners. These feelings are then tempered by the major chords that dominate each phrase, reassuring listeners that yes, this is still a power ballad.

Although the harmony in “Rise” is simple, it is powerful. And it’s arguably the most successful musical component in the work.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Using Open-Tuned Guitar Strings for New Colorful Chords”

Melody

Perhaps the least effective musical component in “Rise” is its melody. The verse uses the same four note leaping motive, adding a final pitch to match the harmony as necessary. The chorus also makes consistency the name of the game, repeating a stepwise motive.

Where the melody of “Rise” really falls short, however, is with the text painting. Text painting (also called tone painting or word painting) is the common technique of using music that reflects the meaning of the lyrics. For example, an ascending line would accompany a lyric about “climbing mountains.” This technique is one of the foundations of Western music going back to the Renaissance, and Perry largely ignores it. There are several times when the melody blatantly disregards the lyrics. The most glaring issue is with the word “Rise,” which is accompanied by a descending figure. When the melody and lyrics clash so obviously critics (and listeners in general) are left wondering whether the song was really finished.

Rhythm

Perry uses a basic rhythmic scheme in “Rise.” She keeps it slow and steady, befitting an inspirational anthem. Following the pop tradition, verses are sparse, letting the vocals carry the rhythmic pulse until drums join during the prechorus. The chorus adds a light backbeat and additional syncopated subdivisions, emphasizing sixteenth note divisions to create more activity and excitement than the eighth note subdivisions used in the prechorus.

Perry’s vocals mirror the overall rhythmic scheme. She uses faster subdivisions in the chorus and adds significant syncopation to the vocal line. The title line, “Don’t be surprised / I will still rise,” uses a string of eighth notes (connecting it to the verse, which also uses consistent eighths), but moves them all off the beat. This technique can be useful for writers who don’t want their chorus to sound too much like their verses.

Lyrics

As I mentioned earlier, Perry has ample experience writing anthems, and the lyrics to “Rise” do more than inspire. Taken alone, the lyrics give “Rise” a biblical sense of importance, driven by constant references to death. The main metaphor in the chorus lyrics invokes Jesus Christ (or perhaps Lazarus), giving the title a sense of grandeur and reverence more commonly associated with sacred music:

When you think the final nail is in

Think again

Don’t be surprised

I will still rise

The nails here might refer to crucifixion, but more likely allude to a nail in the coffin, the traditional idiom for death. Other references to death include “circling vultures” and “fire at one’s feet”. The most popular account of “rising” after death is, of course, Jesus, so the lyrics convey biblical references even without direct references to crucifixion. Moreover, Perry’s Christian background is well documented, so based on these lyrics it doesn’t seem unreasonable to suggest that the song was originally envisioned as an anthem about resurrection. We often compare the Olympics to a biblical struggle, so converting “Rise” to a motivational song for Rio wouldn’t have been difficult.

+Read more on Flypaper: “Music Theory Breakdown: Kanye West’s ‘Ultralight Beam’”

Texture & Timbre

“Rise” uses a healthy suite of electronic effects to build a contemporary pop timbre. Perry’s voice sounds almost robotic at times, and the wide array of drum machine effects blur the line between power ballad and dance remix.

Texture in “Rise” is basically a function of form. Verses are almost entirely vocals, remaining thin and sparse, ramping up through the prechorus into a full ensemble sound for the chorus. The texture thickens considerably during the chorus, aided by the more active drum parts. The texture and timbre of the piece provide direction and offer forward momentum for listeners.

The Verdict

Ultimately, I think that although “Rise” will do its job well and serve as a friendly pop power ballad behind NBC’s Olympic coverage, to me, it feels unfinished and falls short when considered on its own merits. Perry’s lyrics are powerful, and there’s some hidden polish behind the simple harmony, but the stagnant melody’s failure to engage the audience with the lyrics hurts the composition, and this is the lesson for songwriters.

Pop music is often described as being formulaic or “canned.” Even in the cases where that’s true, it’s not necessarily a bad thing. Formulas can be helpful — I certainly don’t want people to mess with the “formula” for a perfect chocolate chip cookie — but ultimately, a formula is designed to help bring together ingredients. Similarly, formulaic writing doesn’t imply a bad song, but when your musical ingredients don’t form a coherent whole, your song will struggle. With “Rise,” Perry just didn’t complete the last step in the formula.