Musical theater nerds are nothing if not extreme. Some people shamelessly love The Music Man and hate Wicked with a fiery green passion. Some people are moved by the rock anthems of Spring Awakening and left cold by the soaring melodies of South Pacific. This enthusiasm for shows of such variety is wonderful, but some people defend their favorite musical like their own child, and unfortunately keep those with opposing opinions at the end of a Titanic-size metaphorical pole. Subjective love and objective quality are two different things; just because you love a certain show, does that mean it’s perfect?

Of course not! No piece of art is perfect, especially ones as entertaining and soulful as musicals. Even the most celebrated shows, from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! to Stephen Sondheim’s Company to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s current hit Hamilton, are not perfect. The sixteenth notes and triple rhymes ask us to think more critically before judging it “good” or “bad.” In my experience, I’ve seen folks do 180-degree turns on their previous opinions, simply by investigating a little further and glimpsing the iceberg beneath the surface.

I will soon be launching a bi-monthly podcast titled, “Some Say: a Musical Theatre Debate Podcast”, bringing in composers, performers, and academics for a friendly debate about the merits and faults of different musicals. But according to the great Stanislavski, “Generality is the enemy of all art,” so I’ve crafted a short framework of guiding questions. It will help us stay objective, but it can hopefully help you as well. Are you heading out to see Fun Home for the first time, or Phantom of the Opera for the twelfth time? Were you cast in a new untested musical or even revising one you’ve written yourself? Try asking these simple questions, and see how the show holds up.

Let’s try an example…

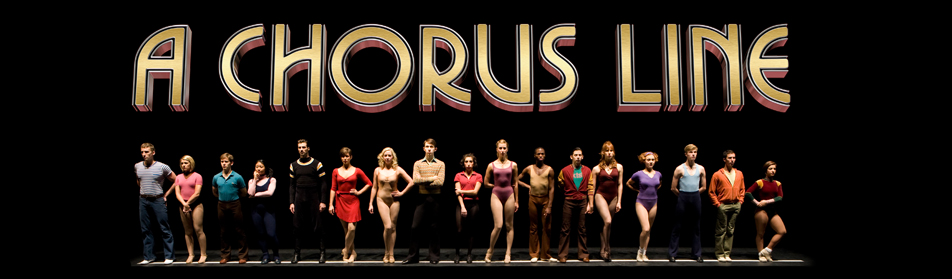

A Chorus Line was written by Marvin Hamlish (music), Edward Kleban (lyrics), and James Kirkwood Jr. & Nicholas Dante (book). The show takes place at a chorus call audition, where the demanding choreographer asks the final sixteen dancers to reveal personal stories in order to get the job. It opened on Broadway in 1975 under Michael Bennett’s direction and was a smash hit, running 6,000 performances, winning nine Tony awards, and prompting revivals all over the world.

Some say that A Chorus Line is one of the greatest musicals ever written. Its fans believe that the depth of its characters is second to none, and that the music is beautiful in an unconventional, intricate, and tuneful way. And some say that A Chorus Line represents the death of Golden Age musical comedy. Its critics believe that the unlikable protagonist and lack of basic plot robs the show of mystery, and that the typical 70s music leaves little room for subtlety, experimentation, or heart. Let’s start digging.

A few questions:

- Story: Does the show tell an interesting story about relatable characters, with exposition, inciting incidents, and a cathartic musical climax?

A Chorus Line creates realistic characters that express themselves in contemplative song, the dialog interplay builds tension, and the climax is unexpectedly thrilling as the dancers parade on stage to the tune of “One”. But their backstories are told through blatant exposition, and the show has little to no plot development (other than the occasional sprained knee or hairstyle argument). So, the storytelling is unconventional and gradual, but the payoff is exceptional.

- Music: Is the music tuneful, melodically and harmonically appropriate, and sufficiently emotional?

Hamlish’s music includes playful showbiz numbers like “I Can Do That” and “Dance: Ten, Looks: Three”, and moving ballads like “At the Ballet” and “What I Did for Love”. He writes a brassy homage to opening numbers of yore, then switches to delicate underscoring, then back to full blast with a tap number. His music keeps the show moving forward, and subverts expectations half the time while adhering to 70s styles the other half. So, the score is slightly scattered, but masterfully pastiche.

- Lyrics: Are the lyrics clever, believable, and matching the characters’ speech patterns and vocabularies?

Kleban’s lyrics are simplistic, with very little rhyme or wordplay (except in comedy songs such as “Sing!”), and phrasing that sounds somewhat pedestrian (specifically in the montage “Hello Twelve, Hello Thirteen, Hello Love”). But when set to the rhythmic 70s tunes, the straightforward lyrics are understandable, relatable, and match the various New York character types. So, the lyrics are plain, but wholly service the music and story.

- Performance: When listening to the cast album or watching the show live, does the integration of music, lyrics, dialogue, and dancing seem consistent, and does the climax of the show cause the listener or viewer to feel joyful and/or reflective?

A Chorus Line analyzes an industry of people willing to sacrifice everything for their love of the stage, and watching sixteen vulnerable people reiterate it may be repetitive, but the message of the show is not lost in tangential songs or filler dialogue. So, the performance is overtly focused, but can be incredibly moving.

So you’re saying…?

Despite its pedigree, A Chorus Line is a flawed show; it is an oddity among traditional musicals and represents a specific (perhaps dated) moment in time, but it also creates an airtight portrait of New Yorkers and makes for an exceptional night of theater. This is just one example. There are thousands of shows to critically examine by asking simple questions, and hopefully by doing so we can better appreciate the admirable but impossible attempt of musical theater writers to perfectly portray the human experience in song.

And it’s quite a singular sensation.

+ Learn more: Sign up for “The Somewhere Project: A West Side Story Companion” for FREE today!

If you enjoyed this analysis, join me for “Some Say: the Musical Theatre Debate Podcast”. Each podcast will focus on a different musical, and bring in two NYC composers, performers, or academics for a friendly debate. We’ll cover everything from Rodgers and Hammerstein, to the Golden Age, to the British Invasion, to current Broadway shows. Take a listen to the intro and look for the pilot episode in November!

—

Alexander Parrish is a musical theater actor, teacher, and composer, and graduated from the BFA Drama program at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. In his spare time, he works as a pianist, music director, and creative entrepreneur. In his off time, he plays Mario Kart to the soaring ballads of “Man of La Mancha”, and writes articles to the screeching violins of “Sweeney Todd”. Check out his YouTube channel here.