+ Ryan Lott (of Son Lux) teaches how to build custom virtual instruments for sound design and scoring in Designing Sample-Based Instruments.

If you’re like most people I know, you probably learned a thing or two about yourself while shut inside during the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in early-to-mid 2020, when the depths seemed to be their darkest and most claustrophobic. My biggest realization from that time was just how much I crave the mental/psychological satisfaction of learning new things.

The sudden absence of musical performances, inability to travel abroad, barrage of video conferences and screen time, and the vanishing of all kinds of other enriching real-world, in-person interactions I took for granted in the “before times” really did a number on my mental state.

This probably explains some of the educational projects I took up that year, in pursuit of new experiences: I made the switch from Logic Pro to Ableton Live; my wife and I learned how to brew kombucha ourselves; I figured out how to stop the cycle of “shanks” in my golf swing by simply distributing my weight further back toward my heels at address…

Big things, all of them, in those days.

I also learned, for the first time, how to properly wield a camera. Or at least, how to press a shutter button, and what words like “aperture” and “shutter speed” were actually referring to.

Despite what I now realize to be some pretty obvious parallels and complements to musical expression, photography was simply one of those things that I felt utterly unqualified to practice. My knowledge of photo-making was, essentially, tinkering with the camera and editing apps on my iPhone, slowly adjusting dials here and there to eventually come up with an image I thought looked okay.

ME: “Hey, wait a minute…isn’t that what I’m already doing with my music half of the time?”

AUDIENCE: [roars with laughter]

In all seriousness, this isn’t far off from the train of thought that led me to buying my first non-iPhone camera. Why couldn’t this be different than the musical path that led me to learn trombone, then bass guitar, then drums, then modular synthesis?

Reading manuals and studying new material had never scared me, but I think I felt some kind of pressure to make a “good” photographic product as a result of this, like I was releasing an album for review or something to that effect. I was worried that the photos I’d be making wouldn’t be good enough to justify the expense.

I had to shake off some (misplaced) anxiety about putting unnecessary, sub-par content into the world, and just remind myself why I was interested in taking photos to begin with.

Any musician or creative person sharing their work can probably relate to this experience in some way: it’s a totally unhealthy way of thinking about creative practices, and the self-doubt convinces you that the world doesn’t need to hear from you, that your contributions have no value, and you shouldn’t bother taking that first step.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “How Do You Eat an Elephant?”

So, while I was selling some gear to come up with the funds for my first camera, I started the endless, mind-numbing research and spec sheet comparisons for entry-level mirrorless cameras. Eventually, at the recommendation of my brother, I picked up a used Canon M50.

Truthfully, my primary use case was filming high-quality video in a low-light basement studio. The added benefit of taking photos and documenting the world around me in a visual way, not just through field recordings, was a nice bonus. I felt I could justify the purchase this way.

Fast forward three-ish years later. Now having 3 mirrorless cameras and having taken thousands of photos, I’m by no means a “good” photographer…at least not in the traditional sense. I still feel that I don’t fully know what I’m doing in every situation, and I’ve filled up a lot of space on my memory cards with bad shots. It’s pretty common for my photo outings to return 0 useable shots. I have so much to learn, but that’s exactly why I keep going. It’s been a rewarding and humbling experience to learn how to take better photos, and it feels just as challenging, rewarding, and open-ended as making music.

I wouldn’t call myself a “good” musician in the traditional sense, either, and I see so many parallels in my DIY, make-it-up-as-I-go approach to these two art forms.

Spending a few years behind a lens has permanently altered my perspective of the world, and I’ve learned so many things about myself and my musical practice as a result. I thought it would be worth sharing 3 things that photography has taught me, all of which I apply to my music-making process.

+ Learn more on Soundfly: Craft more compelling beats with warped and off-kilter rhythms with a new online course by Ian Chang (of Son Lux).

Lesson 1: Lack of Technical Skill Doesn’t Mean Lack of Worth or Merit

Being an improving novice at photography has given me a whole new outlook on my music. It’s given me an alternative outlet to process my inner desire to be creative, and I feel refreshed when I’ve stepped away from the DAW, focused on my cameras instead, and progressed with my photography skills.

No matter how the photos look in the end, it’s still worthwhile to me when I know that I’ve done something to better myself. I take great satisfaction in every new experience with my camera, and I can feel the ripple effects on my musical motivation.

Expression is the ultimate goal of my artistic practice(s), not the quality of the finished good. I have a natural, deeply felt desire to make stuff, and I live to feel the thrill of the creative process playing out as it happens. It’s a rush I can’t live without.

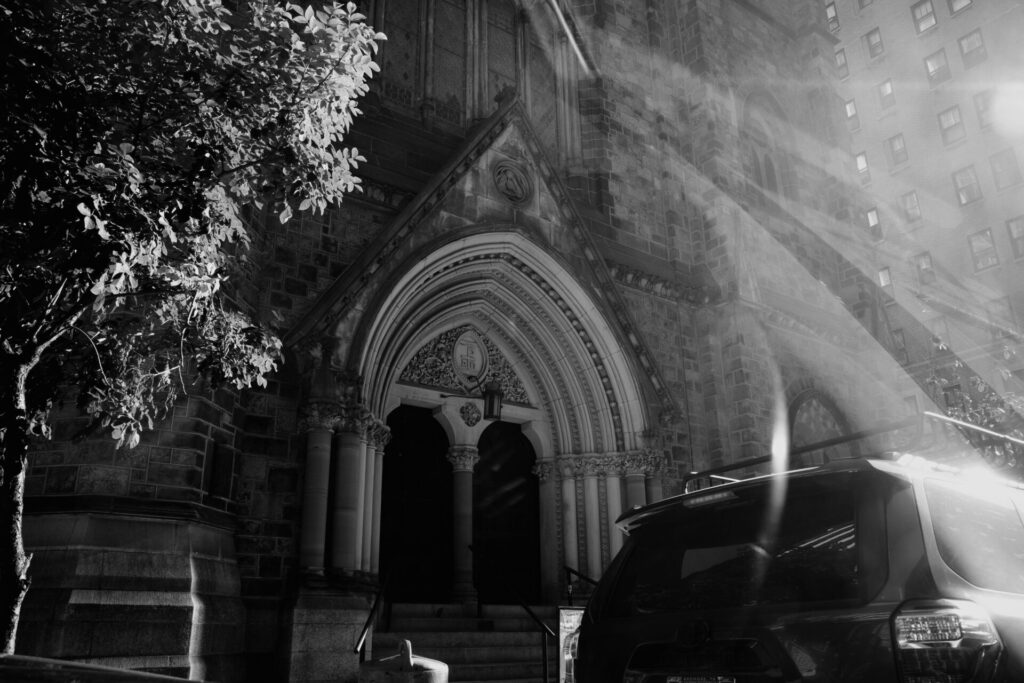

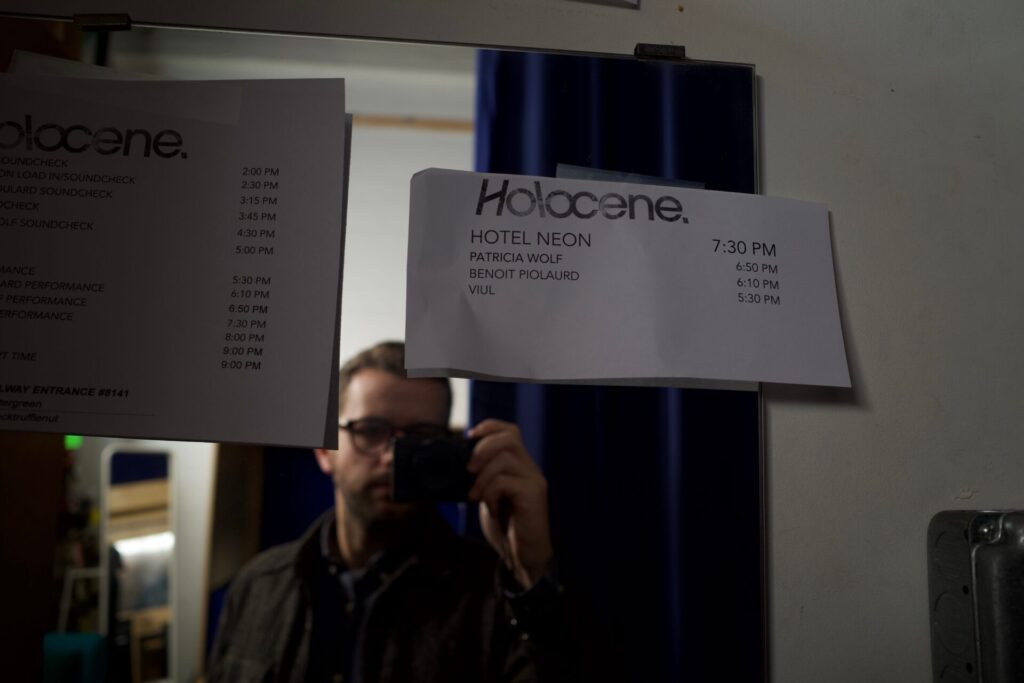

Having a camera available, especially on tour and while making music with others, is another way for me to feel creative.

Lesson 2: Don’t Forget to Have Fun

One of the quickest ways to learn the ins and outs of a camera is to do weird things with it: mess with slow shutter speeds for blurred lights; overexpose an image for washed-out artifacts; throw an object in front of the camera to obscure the focus… play around and see what happens. It doesn’t have to be perfect.

I try to do the same with music by setting up regular “play time” with my gear. I do weird things with no intention aside from experimentation. I simply have fun with it. If we don’t remind ourselves of how fun music can be, it can feel tedious.

Take time to play and reorient yourself with equipment you think you know: wipe your presets and start fresh!

I talked about this notion of “play time” at great length in an interview I did for Fifteen Questions in 2022; perhaps you’d like to read it here for a deeper discussion of this concept.

“I feel like I keep using the word “playful” but I really do feel strongly that whatever I’m making should have some element of fun and play involved. In that sense, the creative state probably feels like a playground in my mind…just trying stuff, seeing what sticks, learning new things. I don’t like the idea of excessive reverence for music, or the inflated sense of self-importance you sometimes hear when people talk about music they’re making or enjoying. Just not my style.”

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Extracting Latent Sound: Composer Lawrence English on Scoring David Lynch’s Photography”

Lesson 3: Make as Much as You Want

When I was learning my way around the camera with my M50, I had to constantly remind myself that it wouldn’t hurt me to just, you know, take a photo every now and then! For some reason I was trying to “conserve” space on my memory card unnecessarily; I was treating digital bits and bytes like finite and precious resources to be conserved. I think the same risk is present for digital music.

Of course, analog storage is another matter… film isn’t cheap, nor is analog tape. But for digital art like I’m making, what’s the excuse to restrain myself?

Occasionally, I have to remind myself that it’s okay to have 2, 3, 6, 10 versions of a track even if I’m the only one who can hear the subtle variations between them. Don’t hesitate to record multiple takes and experiment with new approaches. Let it fly and keep moving forward to find the best result, and don’t stop until you’re satisfied.

Don’t like the result? Delete it and try again.

I think a lot of Daido Moriyama when I catch myself exercising an excessive amount of restraint. He’s one of my favorite street photographers who’s well known for his “aggressive” style of high-contrast images with the Ricoh GRIII. He is a prolific, high-volume shooter, as he describes in most of his interviews about his practice:

“I go ahead and take photos one after another. If I fail, I take another one again. I do not look back on life. Photography is the same for me.” – Daido Moriyama (for Ricoh Japan)

I love this approach. It inspires me to be bold and stop overthinking things. Take the shot! Make the recording! And if you don’t like it, simply try again.

There’s nothing to lose.

Keep on Grooving…

Continue your learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Kiefer, RJD2, and our newest, The Pocket Queen: Moving at Your Own Tempo.