+ Learn to create and arrange original, instrumental hip-hop music from sampling pioneer RJD2 himself in his new course on Soundfly, RJD2: From Samples to Songs.

This article originally appeared on Ethan Hein’s blog.

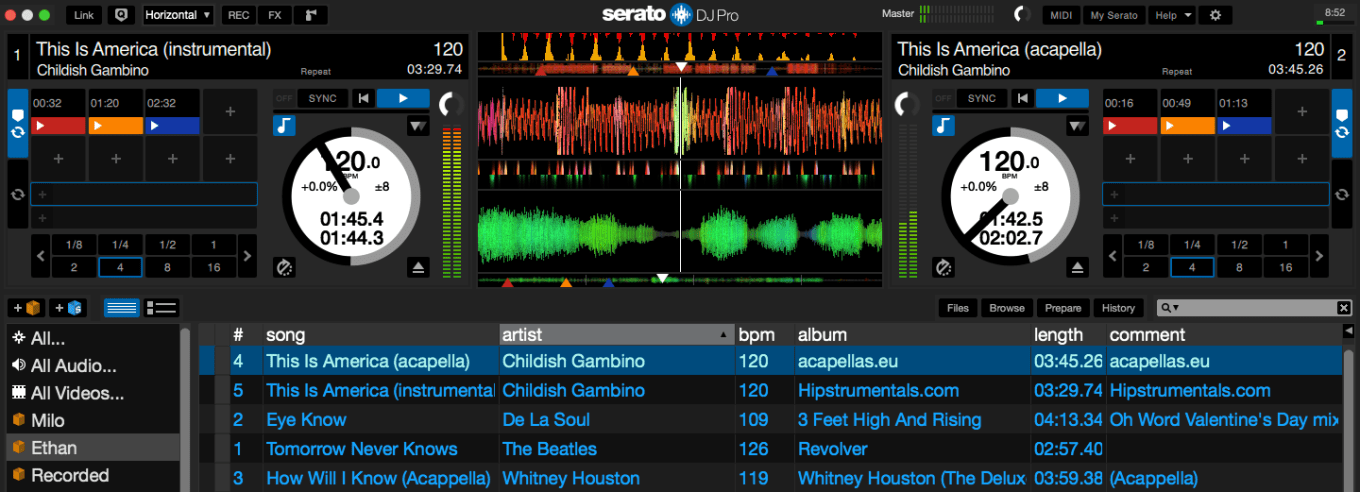

One of my projects for this summer is to realize my decades-old ambition to learn how to scratch. I borrowed a Korg Kaoss DJ controller from a friend, downloaded Serato, and have been fumbling with it for a week now. The Kaoss DJ leaves much to be desired. The built-in Kaoss Pad is cool, but otherwise it’s too small and finicky. I will definitely want to upgrade to something with big, chunky buttons and more haptic feedback in general. Still, the Kaoss DJ is enough to get started with.

For my first serious remix, I thought I would take on Childish Gambino’s “This Is America.” I have the a cappella and the instrumental, and it feels like a timely song. I put the instrumental on one deck and the a cappella on the other, and did my best to improvise a mix in real time. (Email me if you’re dying to hear this experiment.)

I mostly approached this as “soloing” with the a cappella, using the instrumental as my “rhythm section.” But I did some improvising with the instrumental too, by looping, and by jumping around between cue points. I don’t consider this to be a polished work of art or anything, but I discovered some pretty cool sounds, even at my basic skill level. So I’m excited to see where this leads.

I have been improvising with instruments for 25 years now, in many different idioms: blues, rock, jazz, country, and various kinds of electronic music. Scratching is very different from playing an instrument. Intellectually scratching is something like playing loops in Ableton Live’s Session View, but it’s more like playing an instrument, while triggering loops is more like composing.

Scratching has an instrument-like tactile immediacy, and more of the excitement of real-time improvisation, along with the possibility (in fact, strong likelihood) of failure. Serato assists you in some ways — it’s easy to line up tempos, do automated looping, and jump to preassigned cue points. But there isn’t that cushion of universal quantization you get in Ableton Session View.

Every time you touch a turntable, it makes the record go out of sync. Then you have to be very careful to line it back up again. And I’m not even trying to use the crossfader yet. This is all clearly going to take some serious practice.

Music creation software follows a few different interface metaphors: the multitrack mixing desk (Pro Tools), the rack of modular synths (Reason), the sheet of staff paper (Sibelius, Dorico, Noteflight). There are also hybrids of all of the above (Logic). Ableton Live is in a category by itself, because it’s organized around a kind of performable spreadsheet. Serato’s metaphor is two turntables, a crate of vinyl records, and a DJ mixer.

This is an unfamiliar metaphor for me.

I’m an adept editor and manipulator of audio, and am getting to be a solid improviser on a synth. But Serato is like editing audio while it plays in real time, or like performing on a synth made out of a song.

Improvising on an instrument isn’t hard once you have a level of technical fluency. You can play whatever notes you want in whatever order you want to play them, with whatever tone and attack. Scratching is more limited. The music in the recording is set already, it’s in the order that it’s in, and it sounds how it sounds. Any expressive moves you make have to make sense in relation to what’s happening in the recording.

You can see why turntablists like scratching “ahhhh” and “fressssshhhh” so much — they’re structureless slabs of tuned white noise, so they’re more forgiving. Scratching a rap a cappella is another story. The words have meanings, and the pitches have a musical context. When a word falls in the wrong spot or with the wrong emphasis, it sounds much worse than a wrong note in a jazz solo, and an untrained listener is more likely to notice it.

Sometimes you can find unexpected new meanings by recontextualizing vocals, like when I discovered that Whitney Houston singing the words “I know” from her a cappella to “How Will I Know” sounds great over De La Soul’s “Eye Know.” (Email me if you’re dying to hear this experiment.)

The best syllabic recontextualization that I know of is DJ Premier’s use of a Biz Markie vocal in “Nas Is Like” by Nas. When Biz raps the line, “I’m highly recognized as the king of disco-in’,” he pronounces “recognized” as “recogNAAAHZed” with a loud and nasal emphasis on the last syllable. In “Nas Is Like,” Nas ends the first verse, “And of course, N-A-S are the letters that spell…” Then Premier scratches in Biz seeming to say “NAAAS.”

It’s brilliant. I have a lot to learn. See also a more musicological analysis of “This Is America” here.

Lastly, if you’re producing hip-hop beats and looking for inspiration, creative alternatives, and to explore the work of one of the most influential producers of this century, look no further. Check out Soundfly’s new course with turntablist and sampling pioneer, RJD2: From Samples to Songs, in which he explores his creative process in detail, breaks down some of his most famous beats, and flips samples in real time.

Continue learning about beat making, sampling, mixing, vocal recording, and DIY audio production, with Soundfly’s in-depth online courses, including The Art of Hip-Hop Production, Modern Mixing Techniques, and RJD2: From Samples to Songs.