+ Soundfly’s Intro to Scoring for Film & TV is a full-throttle plunge into the compositional practices and techniques used throughout the industry, and your guide for breaking into it. Preview for free today!

Recently, American contemporary composer Nico Muhly published this article on how he actually composes on a day-to-day basis. Muhly’s work involves a great deal of travel which alone can fragment concentration fairly quickly, but he also frequently has to manage several projects at once, responding to commissions and their deadlines, dealing with participants and collaborators, etc.

His working method is thusly somewhat fragmented, and unofficially three-pronged: planning, improvisational research, and finally writing and editing notation.

The commission and its constraints make up the prompt (e.g., “We’d like a piece lasting between 15 and 20 minutes, written for a 65-piece orchestra, by April 23.”). Muhly will start his composition by mapping out his as-yet-unwritten piece’s “emotional itinerary” in the “simplest, bird’s-eye view” (as he puts it). He aims to give his audience something “challenging, engaging, and emotionally alluring” to “create an environment that suggests motion but that doesn’t insist on certain things being felt at certain times.”

He describes this plan almost like an in-flight video map, which cycles between the “overview” (say, London to Singapore) and a hyper-detailed view of small towns and cities in whatever country you happen to be flying over.

Once he’s got the map-document in place, it can “be coloured in and detailed whenever you like.” But this initial map by design excludes the actual musical notes. One example Muhly brings up is a viola concerto he wrote that went something like this:

- Start with a familiar set of chords — a musical home base.

- Then travel as far away from that as possible through rhythmic turbulence.

- Find the way back via a sense of music panic.

Then comes the in-depth research, which can lead to weird and wild places and inform, illuminate, and expand the possibilities for creating a new world for the music to live inside. And then, quite quickly, comes the melodic and rhythmic material.

What he wants is to create an emotional and sonic architecture that gives listeners “simultaneous but radically different experiences.” Muhly is clear to distinguish this method as different from the more typical, and perhaps predictable exposition-climax-conclusion film score means of composing, and yet he also tries to avoid the potentially obscure “bat cave of aggressively perplexing musical jabs.”

Even if the map-document is drawn on a table napkin, it goes into a physical folder — specifically, a three-flap folder that French schoolchildren use — on top of any research notes, diagrams, and photographs. While there are digital copies and other documents that remain in his studio in New York, Muhly likes to bring these folders full of ideas wherever he goes. They act as immediate triggers for reflecting on each individual project, in case he gets any brilliant ideas wherever he is. They’re part of his response to what he calls a “certain poetry of discontinuity” with regards to his focus on the work, set against a constantly changing environment.

What I love about Muhly’s op-ed is how specifically this composer understands and recognizes his own process, and how easy it is to communicate, despite being abstract. He’s identified a kind of cross-stitched method for digital and physical creation and idea storage that is able to exist harmoniously, and dually keeps him organized as he strives to move forward on projects with important deadlines.

This ideation process reduces the amount of wheel-reinvention every time he needs to write music — there’s no starting from square one. And Muhly’s method embodies the antithesis to a major myth of creativity — that of the scattered genius artist, or the “wait-around-for-inspiration-to-strike” artist — substituting it with a vision of the artist as a working professional, an entrepreneur.

He has a system that supports him — one that is bespoke, one that he has tailored to his own specifications — so he doesn’t waste the precious brain space needed to make the good stuff up.

What can you do to systematize your songwriting or composition practice so you can consistently be more creative?

Have you checked out Soundfly’s courses yet?

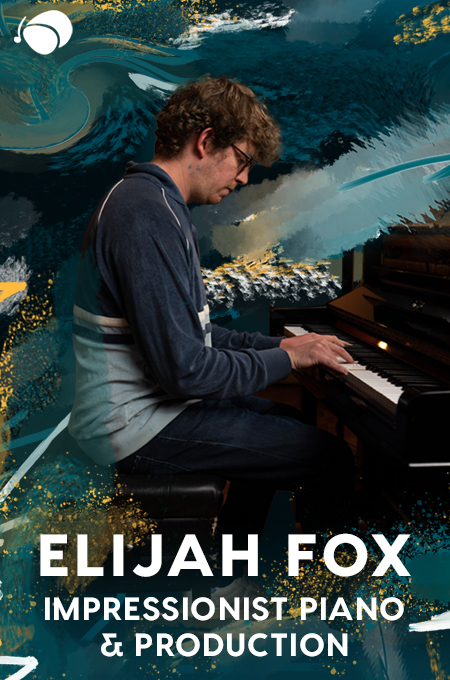

Continue your learning with hundreds of lessons by boundary-pushing, independent artists like Kimbra, Ryan Lott & Ian Chang (of Son Lux), Jlin, Elijah Fox, Kiefer, Com Truise, The Pocket Queen, and RJD2. And don’t forget to try out our intro course on Scoring for Film & TV.