+ Take your modern jazz piano and hip-hop beat making to new heights with Soundfly’s new course, Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production!

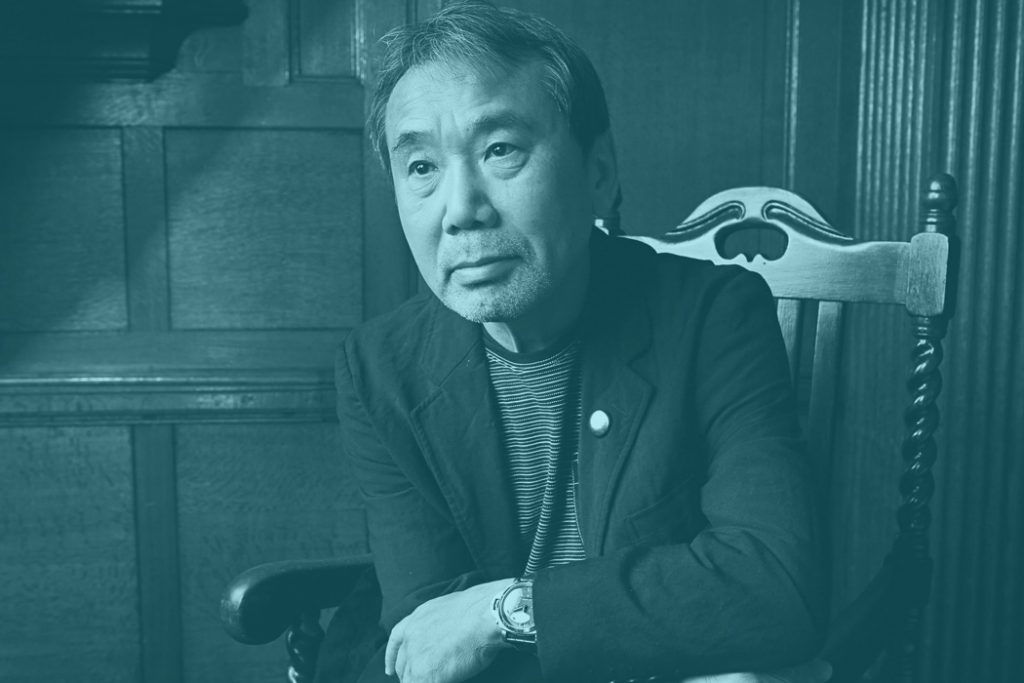

Haruki Murakami is not (quite) a musician, but he has a greater command of music as an art form than most musicians I know, myself included. How is that possible? Read on.

Murakami is considered by many to be Japan’s finest contemporary author. He burst onto the scene in 1979 with his gritty novella, Hear the Wind Sing, a fragmented short story about an unnamed protagonist’s return to his hometown during the summer after a year away at college. He submitted the work to Gunzo for the New Writers’ Prize, then forgot about it. The manuscript he sent in was his only copy, and the piece was only reintroduced into his consciousness when he received a notification that he was a finalist for the prize.

Murakami’s style is defined by cross sections of raw human experience, fused with one part dutiful realism and another part complete lunacy. His work is layered with rich subtext, meanderings, Freudian explorations of the psyche, and heavy doses of fate, sex, violence, and self-destruction. Murakami is the kind of author who makes you feel okay about not being okay. His fiction gives the reader a reason to keep pushing forward, but without the clear promise of bountiful plenty at the end of the line.

Rejecting the Japanese ideals of his contemporaries and predecessors, Murakami breathed new life into the Japanese coming-of-age narrative, using American rock ‘n’ roll and jazz as the framework on which he constructs his unique blend of dramatic realism and mythical storycraft, and developing his voice by approaching his stories in decidedly “unauthor-like” fashion.

In fact, Murakami didn’t even start writing until age 29, and he had no formal literary training. Throughout his twenties, he ran a jazz club with his wife called Peter-cat, in the Sendagaya neighborhood of Tokyo. He describes the inspiration for his first book as an epiphany he had during a baseball game.

I first became aware of Murakami while browsing through a fashion magazine in the lobby of a casting office. The issue was centered on Japan, and Murakami was quoted in a small section about the rich culture of Japanese jazz cafes, continuing to showcase the genre as it was seeming to fade elsewhere in the world. The quote was benign, a snippet from his autobiography. I wasn’t able to track down the original comments, but he rehashes them here for The New York Times:

“Whether in music or in fiction, the most basic thing is rhythm. Your style needs to have good, natural, steady rhythm, or people won’t keep reading your work. I learned the importance of rhythm from music — and mainly from jazz. Next comes melody — which, in literature, means the appropriate arrangement of the words to match the rhythm. If the way the words fit the rhythm is smooth and beautiful, you can’t ask for anything more. Next is harmony — the internal mental sounds that support the words. Then comes the part I like best: free improvisation. Through some special channel, the story comes welling out freely from inside. All I have to do is get into the flow.”

This turned on something inside of me — something that said, “Dre, you have to check this guy out.” I immediately wrote down the name of the author, and went to the bookstore the following morning to purchase Norwegian Wood. For the past year, I’ve been making steady progress through his entire catalog, notching about half of his output. Using two of my favorite stories, Hear the Wind Sing and Kafka on the Shore, I’d like to examine the implementation of music as a literary device and how powerful it can be “off the record.”

Hear the Wind Sing (1979)

“California Girls” (Pages 37-43)

Our nameless protagonist lazes at his parents’ house. It’s 7:15 pm. The phone rings. It’s the local radio station, airing their “Greatest Hits Show.” A mysterious young lady has requested a song be dedicated to our hero (more like an “everyman”). If he guesses who it is, he wins a free t-shirt.

He can’t quite recall at first, but slowly remembers the girl as the disk jockey reveals the song she chose, The Beach Boys’ “California Girls.”

He remembers mundane events from his past; having helped the girl find a contact lens on a school trip, she lent him the record. Maybe something passed between them, the author is vague. It’s not unusual for Murakami to build dialogue with his characters as they run over trivial matters, eventually leading to a much greater emotional reveal for the individual. Music is his weapon of choice in this department. While the song choice may seem arbitrary (after all, this is a Japanese author penning a novel half a world away), it aids in setting the stage and dating the piece. It evokes the sweeping globalization connecting the East and the West in the early 1970s, and imbues the story with the right dreamy, nostalgic quality.

Murakami uses this exchange to reveal finer points of the character’s unique point of view:

“‘…So she thanked me by lending me the record.’

‘Contact lens, huh? … So did you return the record?’

‘No, I lost it somewhere.’

‘Big mistake. You should have bought her a new copy. With women it’s okay if they owe you… hic… but not if you owe them. Got it?’

‘Yes.’”

A seemingly innocent pop song is the secret window into the character’s soul. Murakami gives us the key and Brian Wilson unhinges the lock. We can infer that this individual, while not outwardly inconsiderate, may not yet understand the unintended consequences of his own actions. This girl that he knew many moons ago, who thinks of him on a lonely summer’s night, while his mind wanders elsewhere — she’s buried somewhere deep in his subconscious.

From his response, this sequence of events doesn’t seem to bother him in the least, but perhaps there is something underneath this flexible interior. The core that lets a radio DJ tell him how to treat women, and take it live on the air. This is somebody who carries a guilt that lives somewhere deep inside, somewhere that may never be uncovered.

The next chapter (only a half-page installment on page 39) is an excerpt from the song:

“I wish they all could be California Girls.”

Deep Cuts Only, and a Shot at Redemption (Page 40)

On the following page, the protagonist visits the local record shop to purchase a copy of the Beach Boys’ LP. He runs into a young woman he met at the bar earlier in the week. Having had an awkward first meeting, the conversation gets a bit tense. Our protagonist asks politely for the LP, for whatever reason, logical or illogical. Is he secretly hoping that he’ll see that lost girl? And that he can repay her?

In forthcoming chapters, he attempts to contact the mysterious girl, but he later discovers that she dropped out of school to care for a sick relative. Here is the antithesis of his personality, reflected back to him: giving and taking. The self-indulgent “I” narrator, and the selfless girl putting the needs of others in front of her own.

Next, he asks for a copy of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 37, and “The Miles Davis album that has ‘A Gal in Calico.’” Deep cuts only.

Murakami flexes his muscles here:

“‘We’ve got Glenn Gould and Backhaus, which do you want?’”

The protagonist reveals that they’re a present for a friend. The girl on the other side of the counter replies sarcastically:

“‘You’re a big hearted guy, huh?’

‘So it would seem.’”

Inevitably, he asks her on a date. Redemption? She resists, and refuses, bluntly. He insists, grasping the threads of a personal change. The record store acting as the stage on which the player fights to break from his cocoon. Maybe not on this day, but there is a chink in the armor. This colorful narrative driven entirely by three carefully selected pieces of music, which now become characters in and of themselves.

Simple, Deadly (Page 61)

One sentence at the bottom of page 61 affirms the subtext of the book’s earlier sonic musings:

“We sat there in sullen silence, listening to one song after another on the jukebox: ‘Everyday People,’ ‘Woodstock,’ ‘Spirit in the Sky,’ ‘Hey There Lonely Girl.’”

At this point in the story, it’s been revealed that the narrator has slept with three girls, the last of which committed suicide. A theme develops, and that theme is punctuated here by the jukebox analogy:

- “Everyday People” = An archetype

- “Woodstock” = Time and place (Japan in the late ’60s, following the student uprisings)

- “Spirit in the Sky” = The protagonist’s cry for help, perhaps?

- “Hey There Lonely Girl” = Absolute brilliance, a summation of the developing themes. A mirror of the character’s own loneliness, the isolation of the young girl who left school to care for her kin, the disconnect between the girl at the record store and “I”.

Old, Done Man, Jukebox Hero (Page 72)

The events of the summer begin to compound for our everyman. Another powerful musical reference signals a new development in his emotional maturity:

“And so I continue writing this, plying my consciousness with cigarettes and beer to prevent it from sinking into the sludge of time. I take one hot shower after another, shave twice a day, listen to the same old records over and over again. In fact, the out-of-date sounds of Peter, Paul, and Mary are playing behind me right now. ‘Don’t think twice, it’s alright.’”

Wow. I’ll give you a minute to pick your jaw up off the floor. The music serves two purposes here, as another mile-marker (“out of date”), and as a great crescendo to conclude the chapter. The protagonist is inevitably feeling the void within, his coping mechanisms begin to fail him, he’s only 21, but he’s already an old man. The voice in his head telling him not to think about it — his heart the exact opposite. Five lyrics say more than five hundred words ever could. The power here is in the music, and Murakami knows it. That’s why it’s so darn good.

Kafka on the Shore (2002)

Kafka on the Shore is wholly constructed around a fictional song with the same title. I could write an entire article about the use of that song as a story trope, but in the hopes of encouraging Flypaper readers to investigate on their own and read further, I’m only going to address Murakami’s outside references, that relate back to music we know and love.

The Genesis of Music as the Genesis of Life (Pages 110-112)

On page 110 of Kafka on the Shore, Murakami takes nearly three pages to chronicle a conversation between the protagonist, Kafka, and a new friend, Oshima, over Schubert’s Piano Sonata in D Major, D 850. This, like many musical references in his work, is treated as an opportunity to better understand the deepest inner workings of his characters, as well as give the author a platform to muse on their own feelings about a piece of music.

Oshima explains that he enjoys listening to Schubert while he speeds in his souped Mazda Miata. Diagnosed with hemophilia (a disease which keeps a person’s blood from coagulating, therefore making even a small cut potentially life-threatening) the character uses the piece as a metaphor for the uncertain nature of his own life. He explains that nobody has ever played the piece perfectly, that it is one of the hardest pieces for even an accomplished pianist to master, and that,

“… a certain type of perfection can only be realized through a limitless accumulation of the imperfect.”

As is the case with many of Murakami’s musical injections, here we are given a piece of incredible insight, offered by a fictional character, using music as a tool to answer and create questions about our own existence as we read. These are the kinds of passages that beg for a highlighter and sticky note, journal entry, or existential text to an old friend at three o’clock in the morning:

“‘That’s why I like to listen to Schubert while I’m driving. Like I said, it’s because all the performances are imperfect. A dense, artistic kind of imperfection stimulates your consciousness, keeps you alert. If I listen to some utterly perfect performance of an utterly perfect piece while I’m driving, I might want to close my eyes and die right then and there.’”

Music as a Catalyst (Pages 325-329)

In Chapter 34, a supporting character, Hoshino, an unassuming trucker who is mixed up in an out-of-this-world adventure, stops into a small coffee shop, where the owner is playing Beethoven’s Archduke Trio (Piano Trio, Op. 97), on the turntable.

This piece becomes a battle cry for Hoshino’s journey from living outwardly to turning within and examining his place in the world. Murakami once again flexes his muscle, having the characters debate the finer points of the Rubinstein-Heifetz-Feuermann version and the “more structured, classic, straightforward version,” while using the composition as fuel for the character’s exploration of his consciousness. Hoshino purchases a discount bin copy of the piece at a record shop the following day.

The Beethoven piece, along with a Hayden composition the shopkeeper introduces, bring Hoshino back to his childhood, as he reflects on this part of his life, a part that he hasn’t connected with in quite a long time, he gleans this beautiful bit of insight:

“As long as I was alive, I was something. That was just how it was. But somewhere along the line it all changed. Living turned me into nothing.”

Depressing? Not quite.

Having put his job on hold to embark on what is essentially a wild goose chase, Hoshino makes the decision at this point to follow that road to whatever end, in lieu of his other responsibilities, or rather, the things that seemed important to him before unprecedented circumstances opened his eyes to something he never could have imagined. Something that fills him with a new sense of purpose.

I think we can all recall moments when art has lifted haze from our eyes. It isn’t unusual for music to be the vehicle that brings us to a point of self-awareness — exercising this power inherent in literature is an incredible way to fuse two of the most emotionally potent outlets on the planet, because as the music informs the character’s experience, it also informs our own.

Without giving too much away, Hoshino becomes sort of a reluctant hero as the story draws to its conclusion, while the Archduke Trio continues to make cameo appearances, giving the reader a barometer on Hoshino’s development. Again, Murakami has used a piece of music as a powerful catalyst for forward movement in his narrative flow.

Sounds of Silence (Page 138)

A short while later, we find Kafka laying low at a cabin the mountains, going through the motions of each day while he contemplates his past, present, and future. As he struggles with abandonment issues, and comes to grips with the inevitable mind bending that accompanies a weekend tryst into the middle of nowhere, Kafka lies down to sleep, listening to “Little Red Corvette” by Prince, on his Walkman,

“The batteries run out in the middle of ‘Little Red Corvette,’ the music disappearing like it’s been swallowed up by quicksand. I yank off my headphones and listen. Silence, I discover, is something you can actually hear.”

This is a loaded statement. Not only as a narrative force in the story, but as a commentary on music in the macro and the microcosms of our lives. Silence, many argue, is just as integral to the quality of music as the “music” itself. It is the space that breathes life and brings drama to the work.

Just look at John Cage’s “4’33,” a piece of music with no written information, wherein the pianist sits quietly at the piano for four minutes and thirty three seconds, allowing the room tones, and sounds of the concertgoers to create the piece. Maybe this is extreme, that’s an awful lot of space. But without respite, constant noise wears on our brain, ears, and ability to appreciate something.

This is especially true as it extends to how we now consume music. Throughout history, music, like most things, has become increasingly and more readily available. In days past, music was only enjoyed by the bourgeoisie, or by a community within which certain members of that community learned folk songs and carried an oral tradition of storytelling through songcraft. Even extending to the advent of recorded music, records were expensive, the devices required to listen equally so. As competition drove down costs, owning a turntable became commonplace. By the 1960s, “Album Rock” was ushering in a whole new wave of rock and pop, which would begin changing the world as we knew it.

As transistor radios became more widely accessible, and FM radio began to overpower AM in the United States, music began to fill every space of our lives. Silence became something we no longer understood; a luxury we couldn’t afford — and something that became increasingly uncomfortable. With the advent of 8-track, the Walkman, and later the iPod and music streaming, recorded music has become so accessible that it’s been entirely devalued.

Music is everywhere. It’s on TV, in movies, at the grocery store, on the radio and in the background of every piece of media that we consume. For so many, music is simply wallpaper.

The point is, there is a gray area between availability and significance. Something is considered special when it’s in limited supply, and the courage to invite silence into our daily lives is waning. Something as profound as silence is often overlooked, especially by creative types, who are constantly pursuing stimulation.

I’m not opposed to music being so readily available at all, in fact, I think that’s exactly as it should be, and part of the natural evolution of information being given to the people, when it was previously only available to the privileged. That being said, so much bombardment often leads us to forget what we are listening to, and in effect, makes it difficult for us to enjoy the lack thereof. Maybe we can all take a cue from Kafka and let the batteries die every once in awhile, you may find that when you return from the silence, you’re hearing something totally new.

A Wild Sheep Chase (1982)

Murakami admits to practicing a bit of piano in his youth, but he never became a proficient musician. There are numerous references to practice, talent, and the characters’ ability (or lack of ability) to play instruments, mostly guitar, throughout his stories.

Musician Jokes (Page 320)

On page 320 of A Wild Sheep Chase, Murakami details an exchange between the same unnamed protagonist featured in Hear the Wind Sing and a mysterious character known only as “the Sheep Man.” (Note: the Sheep Man speaks in garbled English, typed with no spaces. I imagine the translator saw fit to use this device as a technique to interpret a specific dialect or characteristic of the original Japanese.)

“‘Youwereplayingguitar,’ said the Sheep Man with interest. ‘Welikemusictoo.Can’tplayanyinstrumentsthough.’

‘Neither can I. Haven’t played in close to ten years.’

‘That’sokayawplaysomethingforme.’

I didn’t want to dampen the Sheep Man’s spirits, so I played through the melody of ‘Air Mail Special,’ tacked on one chorus and an ad lib, then lost count of the bars and threw in the towel.

‘You’regood,’ said the Sheep Man in all seriousness. ‘Probablyloadsoffuntoplayaninstrumenteh?’

‘If you’re good. But if you want to get good, you have to train your ears. And when you’ve trained your ears, you get depressed at your own playing.’

‘Nahc’monreally?’ said the Sheep Man.”

If you’re a musician, you know exactly what the narrator is trying to express. It reminds me of the stage of artistic development that music educator Anthony Wellington refers to as the state of “Conscious Not Knowing” (in the video below).

It’s the stage at which we become aware that we need to improve and need to make the choice to do what it takes to learn. It’s a high summit, and at that point, we are collectively standing at the bottom looking up.

The best part is… every artist, musician, athlete, intellectual and craftsperson has been there, and as individuals like Haruki Murakami show us every day, it’s never too late to start your ascent.

Play Your Heart Out!

Continue your learning adventure on Soundfly with modern, creative courses on songwriting, mixing, production, composing, synths, beats, and more by artists like Kiefer, Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Ryan Lott, RJD2, and our newly launched Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production.