+ Our brand new course with The Dillinger Escape Plan’s Ben Weinman teaches how to make a living in music without making sacrifices. Check out The Business of Uncompromising Art, out now exclusively on Soundfly.

It’s 1985 — about 100 people are standing around in a local concert hall in Ulaanbaatar, the capital city of Mongolia. Cigarette smoke and the murmur of social activity fill the air in equal measure. Members of the band Ayasiin Salkhistep step onto the stage to set up their instruments.

Despite the country’s Soviet-allied government placing restrictions on anything it deems as promoting Western ideals, many in the city are familiar with rock and roll, thanks to records and tapes that made their way into the country via black market smugglers or people returning from traveling through the Soviet Union, where contraband from the West is easier to obtain. But once the first guitar chords strike, it’s apparent that Ayasiin Salkhi aren’t playing the rock and roll on those black market records. This is something strange and new — this is heavy metal.

As Mongolia’s first-ever metal band, Ayasiin Salkhi, were pariahs in the 1980s.

Heavy metal was relegated to the fringes of Mongolia’s contemporary musical conscience. But metal has clawed its way up over the last 30 years, and now boasts a growing, dedicated following and its own festival in the steppe nation.

One of the Mongolian metal scene’s most ardent supporters is Unenkhuu Umbanyamba, or Uugii, the man behind Mongolia’s biggest annual heavy metal event, Noise Metal Festival, which marks its five-year anniversary this coming autumn. After seeing how heavy metal festivals in other countries brought like-minded fans together, Uugii felt Mongolia’s metal community needed one of its own.

“We needed this festival to play, to express ourselves, to, you know, just let our energy and emotions go,” he says.

The first Noise Metal Festival took place in 2014 at UB Palace, a venue in the capital. Uugii was equal parts excited and nervous at the uncertainty surrounding that inaugural event.

Ten bands were booked — eight local and two foreign acts — yet the execution of the event fell short of Uugii’s expectations. “It was a failure, but a big learning experience,” he recollects, noting production difficulties and the sizeable debt he incurred from renting all the equipment at exorbitant rates.

When asked why the difficulties didn’t deter him from throwing a second festival the following year, Uugii put it simply:

“First is the passion I have for the music. Secondly, if I didn’t do it, nobody else would.”

Subsequent iterations of Noise Metal Festival have gone much better, with the turnout growing each year and international acts from Canada, Russia, Japan, and Singapore joining the home-grown lineups. But Andy Teesh remembers when that wasn’t the case in Mongolia. He was the front-man for Ayasiin Salkhi at that 1985 show.

As a high school student, Teesh’s grades and aptitude in extra-curricular activities earned him a scholarship to study in Russia at a police training school in Volgograd. An Iron Maiden tape made its way into Teesh’s possession when he was visiting Moscow, giving the young Mongolian his first taste of the music that would divert his trajectory as an aspiring officer.

Because Mongolia had close ties to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, many of the nation’s citizens were living, working, and studying in Russia. Teesh met other compatriots who also fell in love with heavy metal — so much so that they wanted to play it.

“I got the idea to start the band in 1984. I met this kid in Moscow that was still in high school but could play the guitar… I met another kid who used to live in Odessa that played the drums really well, another kid who played bass,” he says. “We all thought that we needed to start a heavy metal band back home.”

And the group became Ayasiin Salkhi (or “Fair Wind” in English) a name that served as something of an antonym to what you’d expect of a death metal band, “like ‘Death Hurricane,’” Teesh says with a laugh. The name also kept the band off any intrepid censor’s radar.

By 1985, all members of Ayasiin Salkhi were back in Ulaanbaatar, having spent the previous year practicing their sound. In that time, Teesh landed a job with the Investigation Department of Mongolia’s Ministry of Justice, a position he is still proud of. In stark contrast to the long-hair, black skull cap, Iron Maiden shirt, and combat boots donned on any given day, Teesh’s black-and-white pictures from the time show a clean-cut, fresh-faced investigator, complete with the crisp, grey uniform of his profession. But that didn’t stop the band from practicing constantly.

“When I came back, I earned the rank of lieutenant,” he says. “I even played in the Investigation Department’s band. However, I started to put Ayasiin Salkhi first and spent more time practicing because, in the end, I was a metal head.”

That was the same year Ayasiin Salkhi had their ill-fated inaugural show.

Teesh recalls: “Our show was really badly received. It was very different in Mongolia back then. The way we were behaving on stage, with the head-banging, our look, and our singing style — for most of the people in the audience, it was very nightmare-like, almost like we were evil.”

There was an almost immediate media blackout enforced on Ayasiin Salkhi. No newspapers were allowed to write about them, no TV stations were allowed to broadcast about them, no radio stations were allowed to play their music. Teesh started to get pressure to abandon heavy metal from family members, friends, and by his superiors at the Investigation Department.

“My bosses told me: ‘Criminals and gangsters listen to this music, so if you are an investigator, be an investigator.’ If you played metal music during communist times, you were seen as supporting Western ideology, as well as disrespecting your own art and culture. In other words, you lacked communist ethics and ideals,” says Teesh.

Mongolia ended its status as a satellite state of the Soviet Union with a democratic revolution in 1990. Just as the country had chosen a new direction, Teesh too had a choice to make that year: a career as an investigator or a life in heavy metal… He chose metal.

“There were few fans, no income, and no respect for us,” says Teesh, who still fronts the band today. “Our families and friends even told us to quit, but it didn’t matter because our hearts were in metal music that much.”

Mongolia’s revolution ushered in a new wave of openness to the outside world in the 1990s, but some of the old biases against what many deemed as Western culture remained.

Uugii is a member of the generation of Mongolian metal heads that began to openly embrace the genre in the 1990s. Rock and roll was increasingly celebrated, and was even commemorated with a monument dedicated to The Beatles erected in Ulaanbaatar. (The Beatles being one of the bands many growing up in communist Mongolia became fans of through illegal record swaps.)

Still, heavy metal and the culture that came with it chafed against the social sensibilities of 1990s Mongolia. “Back in the day, people would say ‘Those metal-heads, or whoever listens to rock, are potheads who are just into drugs and sex,’” says Uugii. “This kind of perception carried onto the next generation and people saw people like me and would say, ‘Oh, you guys who listen to this really heavy music probably do drugs,’ but I don’t even smoke cigarettes.”

That experience sowed the seeds for Uugii to later launch Noise Metal Festival, seeing it as his “mission” to one day “help people here understand metal music more as a form of art.”

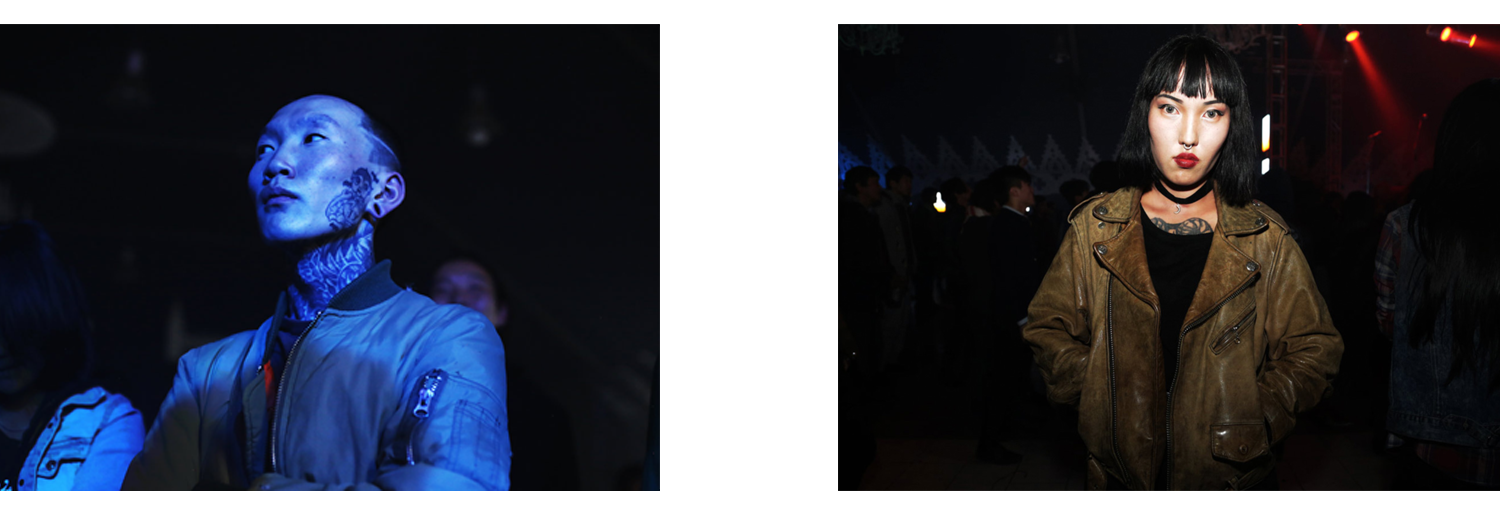

The genre has come a long way in Mongolia since then. Local heavy metal albums can be found in the capital’s music stores, and the internet has ushered in a new era of music discovery for the country’s mostly young population. The new generation of Mongolia’s metal heads faces much less resistance in society. According to some, that fact has fostered a greater willingness in the youth to express themselves however they see fit. And Noise Metal Festival has become a place where all generations of the country’s metal heads gather.

Battulga Khurelbaatar is the lead singer of one of Ulaanbaatar’s up-and-coming heavy metal bands, Growl of Clown. The 21-year-old has taken the stage at Noise Metal Festival with his band for the past three years. With a greater ability to express oneself, he says it’s a lot easier for metal fans to build a sense of community in the country.

The young metal head also sees the genre as having a positive influence, a departure from the biases of the past. “This whole metal thing, I’ve never regretted pursuing it or the things I’m doing. Some people may think they may be better off if they choose a different route, but listening to metal music has been a very positive influence on me,” says Khurelbaatar.

Ayasiin Salkhi has also graced the stages of Noise Metal Festivals. After the turbulence of their first 20 years as a band, they released their first album in 2004. They’ve also racked up countless performances both at home and abroad. Yet, to Teesh, Noise Metal Festival is still an important event for both his band and Mongolia’s metal community as a whole.

“The festival is helping the Mongolian metal scene to grow further. Hopefully, it will attract more metal bands and attendees from abroad to come and experience Mongolia, to see this scene,” says Teesh. “I want more people to experience Mongolian heavy metal.”

While Mongolia’s heavy metal scene has grown, Uugii is still the main force behind its biggest event. Support from outside the metal scene ebbs and flows; the festival has test-driven three venues in its four years of existence, though none is quite a perfect fit. Promises of sponsorship and more commercial funding for Noise Metal Festival often come and go. He generally bears the brunt of the work and financial responsibilities of organizing it. Last-minute changes to the lineup have happened at every festival. Still, the growing turnout year after year means that things are still going more right than wrong.

Despite the difficulties, Uugii expresses no intention of stepping away:

“When I think about myself, you know, ten years from now, I’ll probably still be doing Noise Metal Fest. I’ll do it for as long as I can. I don’t really feel like I have any other options except to keep doing it.”

Words and Photos by Bejan Siavoshy

Rev Up Your Creative Engines…

Continue your learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, RJD2, Com Truise, Kiefer, Ryan Lott, and Ben Weinman’s The Business of Uncompromising Art.