+ Learning to read and write music? Access hundreds of lessons from Soundfly’s online courses on music theory, songwriting, production, mixing and more — subscribe here.

There are many contenders for the title of the 20th century’s “greatest opera,” and Alban Berg’s transgressive magnum opus Lulu is undoubtedly one of them. Love, eroticism, and death have always been stalwart themes of opera, yet Lulu still has the ability to surprise audiences through its unflinching examination of these themes — in part due to Berg’s incorporation of a complex, full-orchestral palindrome at the heart of the work.

We’ll get to that in a second — let’s talk about the opera first.

Based on a narrative from the avant-garde writer Frank Wedekind, Lulu details the rise, fall, and violent death of a sexually adventurous dancer (murdered by Jack the Ripper, no less). It shocked readers by showing true love and romantic opportunism side by side, criticizing what Wedekind saw as the hypocritical bourgeois attitude towards sexuality at the time. The story has continued to resonate throughout the years, and the story’s place at the center of Metallica and Lou Reed’s controversial collaboration only speaks to its ability to both entice and polarize audiences.

Lulu’s creation mirrors the themes of its plot. Berg started writing it after being emboldened by the success of his first opera, Wozzeck, in the 1920s. He made significant progress but abandoned the project following the death of Manon Gropius, a muse of Berg’s and essentially he and his wife’s adoptive daughter. By the time the violin concerto he dedicated to Gropius debuted, Berg himself had already died at age 50. Blood poisoning took his life on Christmas Eve in 1935, and Lulu was left only one-third orchestrated.

We’ll return to the story of its eventual completion later, noting that at the time of his death Berg had already completed all the thematic compositional material for the opera. Lulu is famous for pushing the strictures of serialism to their limits. Serialism is one of the most important musical movements of the 20th century, and in brief it treats all 12 notes of the chromatic scale as possessing equal value and forbids any regression back to conventional tonality.

The building block of serialism is the 12-tone “row” in which all chromatic notes are articulated in an order chosen by the composer. The row can then be developed in several different ways. For example, inversion flips the vertical structure of the row (an inverted row will descend if it ascended before); retrograde motion plays the row in reverse.

Berg understood that these mechanical principles were only techniques to aid the communication of emotion, rather than ends in themselves. While freeing himself from the conventionality of earlier compositional techniques, he also relaxed many of the dogmatic rules handed down by his teacher (and serialism’s doctrinaire evangelist) Arnold Schoenberg.

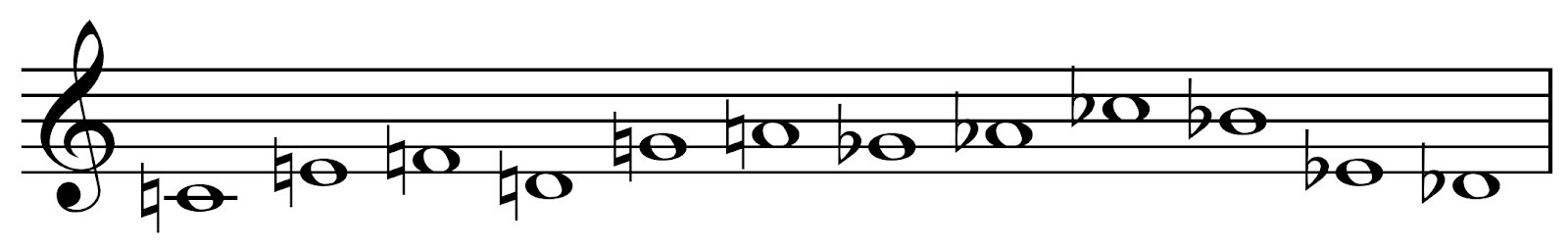

All this was in aid of reinforcing the narrative and emotional quality of his work. And so, Berg’s Lulu features not just one tone row but several. This not only creates a welcome diversity of harmonic material, but clearly harks back to earlier operatic techniques such as Wagner’s famous leitmotifs. For example, the tone row associated with the character Lulu herself is rendered in C as follows: C E F D G A G♭ A♭ C♭ B♭ E♭ D♭.

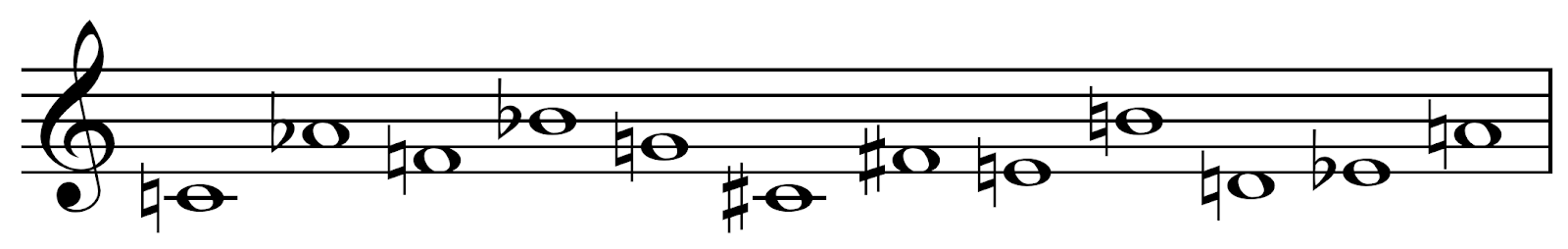

For Lulu’s lover, Alwa, the row in C is as follows:

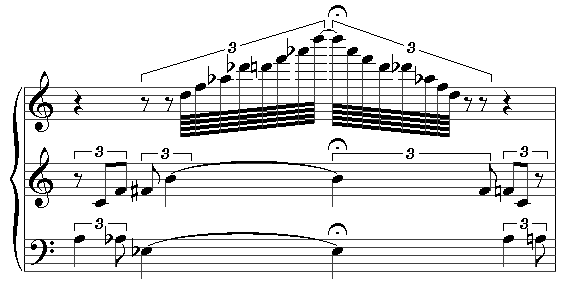

Berg was obsessed with numerology and symbolism. Lulu is accordingly littered with geometric expressions of human themes as above. The most notorious example of this obsession comes into play during the piece’s famous musical palindrome, hinging at bar 687 of the score.

Lulu has been languishing in jail, and the stage directions require a pre-recorded film to play, which begins to run in reverse halfway through the reel. The music matches this, pivoting on dense piano arpeggio that mirrors its ascent and descent:

For a particularly clean and easy-to-follow rendition of this section, check out this video, which follows the full orchestral score through the Act II interlude.

Although the extent of this symmetry seems strange and eccentric, this idea isn’t actually as bizarre as you might think. Thematic inversion had been used by composers as far back as Haydn. The Second Viennese School, under which Berg had been educated, considered playing melodies backwards part of the library of techniques that could replace tonality.

As mentioned before, Berg was looking to push these techniques to their limits — not only in terms of scope, but also intent. The trajectory of this orchestral inversion actually mirrors the trajectory of the story.

In the story, Lulu is loved by many, but manipulates her lovers, moving from one to the next. At the height of her adoration, her fortunes begin to fall: she’s chased by the police, imprisoned, forced into prostitution, and then eventually murdered. To drive this musical and thematic symmetry home, Berg specified that the actors that play her first three lovers are the same actors that play her last three clients when she is a prostitute. This dramatic palindrome dovetails with the musical palindrome: Berg’s marriage of disturbing musical formalism with dramatic technique highlights Wedekind’s unearthing of the violence within patriarchal sexuality.

Berg’s wife, Helene, initially worked hard to achieve the completion and premiere of the unfinished opera in 1937. It was performed as an incomplete work by the Zürich Opera in 1937, and people craved more. She initially asked Schoenberg to definitively finalize the work, but he declined. However, she soon became resistant to any lasting completion of the unfinished orchestration, perhaps as a result of a unique harmonic mystery being solved.

An annotated score of Berg’s Lyric Suite was discovered, which he secretly dedicated to Hanna Fuchs-Robettin, with whom he was in love. Without delving too deep, the secret meaning of the Lyric Suite also made its way into Lulu, where Berg’s special use of the two notes, H (musical German for B) and F — for “Hanna Fuchs” — made yet another example of Berg’s unique predilection for coding emotion in musical geometry.

Helene Berg knew of her husband’s love for Fuchs-Robettin, and it seems likely her attempts to scuttle the completion of Lulu were at least in part motivated by this. She died in 1976.

In the meantime, Lulu languished, almost complete. Three long stretches of music were fully orchestrated, and the rest clearly sketched by Berg in a manner where completion would require almost no guesswork. The unfinished version had been performed a number of times across the globe between 1937 and 1976, but Universal Edition, the composer’s publishing house, knew that Helene Berg alone was standing in the way of this great opera being fully released to the public. So, they started secretly commissioning their own final version to be completed by Viennese composer Friedrich Cerha.

Cerha utilized the bank of harmonic direction that Berg left behind in his piece — the geometry and notational patterns — to finalize the movement and motion of the remaining material so that it was as respectful to Berg’s musical linguistics as possible. After Helene’s death, Cerha’s secretly finished version could finally be unveiled through a 1979 performance led by conductor Pierre Boulez. The rest is history.

Lulu the character may have met with a brutal fate, but at least Lulu the masterpiece was saved from an equally terrible punishment in obscurity. Berg, to quote a great German philosopher, was all too human. It’s this deep emotion that shines through in his work, mediated as it is by the most formal of compositional techniques.

Get 1:1 coaching on your composing and arranging from a seasoned pro.

Soundfly’s community of mentors can help you set the right goals, pave the right path toward success, and stick to schedules and routines that you develop together, so you improve every step of the way. Tell us what you’re working on, and we’ll find the right mentor for you!