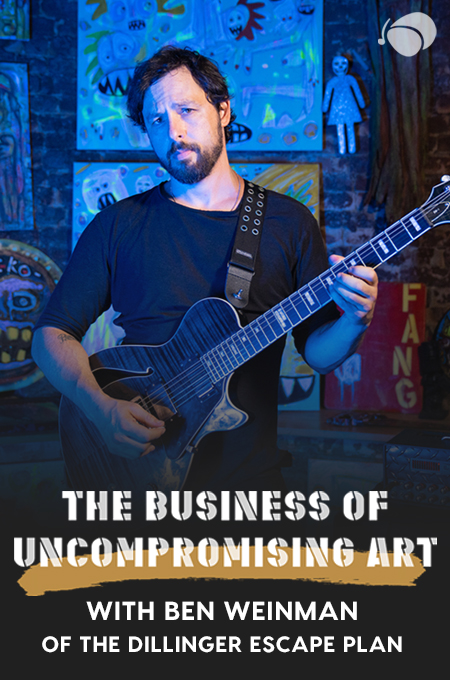

(Above) “The Old Plantation (Slaves Dancing on a South Carolina Plantation)” [ca. 1785-1795]. Attributed to John Rose, Beaufort County, SC. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, VA.

Today is the United Nations’ International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. We wanted to take this commemorative opportunity to shed some light on this extremely painful part of global and North American history, to both celebrate the purpose of the UN’s dedicated day of remembrance, and to have a chance to talk about the ways in which slavery contributed positively to the artistic development of American culture.

When remembering the transatlantic slave trade, it’s easy to dwell on the horrors of the experience of slavery. However, as a product of the African diaspora myself, I can definitively say that I am grateful for the legacy I inherited — a legacy that contains brilliant scholars, inventors, and artists who, within the 20th century, managed to change the course of music, literature, and culture in profound ways. The resilience and resistance African slaves demonstrated in the face of oppression was the catalyst for an unprecedented amount of innovation. American music as an idea has been largely shaped by the byproducts of this resistance: blues, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, gospel, hip-hop, and so much more.

In 2014, I was fortunate enough to visit the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool, England. There I saw images that disturbed me to my core. But the beauty of this museum is that in addition to all of the traumatic images on display, there was also a section that focused on the many cultural gifts that have been given to modern society as a result of the antiquities of the slave trade. Despite that the after-effects of this era still haunt much of North America and the world, we are all beneficiaries of these cultural and artistic gifts.

Let’s unpack how the legacy of the slave trade has made it from the early music of African slaves to genres that have become “as American as apple pie.”

Slave Songs/Spirituals

One of the main casualties of slavery was language. Africa is a continent rich with many different countries, cultures, traditions, and languages. Most of the slave population that was taken across the Atlantic Ocean between the 17th and 19th centuries came from West Africa, and that region alone is just as diverse as all of Europe. So when the first African slaves arrived on American soil, many of them could not communicate with each other. Families and people from the same region were also separated, on purpose, so that ethnic and tribal communication would be even further limited amongst the slave population.

Because slaves were often prohibited from practicing traditional religions and customs from back home, new languages and dialects were created in the New World to hide elements of culture and communicative devices from their captors. These elements from African culture were able to subversively survive through music, among other ways.

Early slave songs known as spirituals were adaptations of the hymns that new slaves were taught during Sunday worship. One of the most interesting paradoxes of slavery was that despite the blatant cruelty of this dehumanizing practice, there was still an insistence that slaves worshiped “God” and become Christian. On most plantations in the American South, Sundays were considered a day of rest and slaves were allowed time to study scripture, learn about the Lord, and practice worship. This meant that Africans were allowed to play music, sing songs, and commune.

In places like Congo Square in New Orleans, slaves made use of this allowance to play the drums. And although this may seem like a minor detail, the rhythms and songs they learned and taught each other would go on to lay the foundations for so much of modern gospel music, let alone spread across New Orleans and the rest of the South to influence delta blues, jazz, and swing.

Singing hymns during Sunday worship was one of the few moments slaves were able to express themselves freely. As more of the population began to adopt Christianity, slaves were allowed to sing these songs while they worked, and stories of their lived reality began to seep into the narratives. Tales of freedom and salvation, their current plight mixed with a religious sensibility, forged together to create new spiritual songs to teach younger generations how to escape this earthly nightmare — in some cases, very literally.

A great example of this can be found in the song “Follow the Drinking Gourd” below.

Although there are many different interpretations of this spiritual song, many believe that it was used as an instruction for runaway slaves to escape to the North, disguised as a biblical story. The drinking gourd refers, of course, to a literal gourd used to gather water, but was also used as a code to follow the Big Dipper constellation which points to the North Star. Many of the other lyrics speak of specific places to run to, and how to travel there.

It is even believed that Harriet Tubman used songs like this to help guide runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad. The legacy of “Follow the Drinking Gourd” extends beyond the 19th century, and has been performed by artists as diverse as Taj Mahal and John Coltrane, whose “Song of the Underground Railroad” is based on the melody of this song.

“Wade in the Water”

“Wade in the Water” was first published officially in 1901, but it’s been around for much longer. Scholars believe that this song was used to transmit secret codes to runaway slaves. Wading in the water referred to instructions to hide in the water and leave the main trails, so as to evade the search dogs. Metaphorically, though, water is a symbol of rebirth and transformation in Christianity and other religions. The song also makes reference to the Israelites who famously crossed the Red Sea to escape their own bondage in the biblical story of Exodus.

“Wade in the Water” has made an imprint on pop culture and has been covered by a wide range of artists including The Staple Sisters, Ramsey Lewis, Eva Cassidy, Billy Preston, and more. In my opinion, its popularity is a testament to the transcendental nature of the song’s meaning and melody: a haunting call to be still and wait in the face of impending danger, which is a sentiment with which many generations of Americans can identify.

Spirituals were some of the first music by African Americans to eventually be published and recognized by Americans nationally. Ensembles such as the Fisk University Jubilee Singers popularized spirituals by performing them on tour and recording them, leading to more groups doing the same and helping bring these songs into the mainstream.

Work Songs

After the abolition of slavery in the mid-19th century, the economy of the southern states took a devastating blow. Unable to adjust to the efforts of reconstruction to try to provide a balance to the population, new laws were made that essentially criminalized much of the behaviors of the newly freed African American population. Those who were unable to find work were arrested for loitering and other minor offenses, and were sent off to do prison labor. Others who couldn’t find work ended up becoming sharecroppers on plantations and doing the same grueling work of plantation labor for next to no money, and slave songs started to turn into work songs.

Recordists John and Alan Lomax traveled throughout the South in the early and mid-20th century recording these work songs in a variety of places, but significantly in prisons. Oftentimes prisoners would have to chop down trees, and the push and pull of two different groups alternating strikes with their axes created a two-beat rhythmic pattern that the workers could sing over.

The music of these work songs was similar to the spirituals, but the content took on more secular material — often using metaphors to personify their labor as something else, and with way less scrutiny from the plantation owners. These songs were sung by prisoners, sharecroppers, and the now-freed slaves, who still had to resort to grueling manual labor either by force or financial necessity.

Scholars have noted a similarity between the work songs of the Antebellum South and the work songs of Ghanaian fishermen. Listen:

Musically, work songs tend to be more harmonious than the spirituals in their basic form. At this point, African Americans had had access to instruments and were allowed to sing more freely. This is not to suggest that all spirituals were sung in unison, monophonically, but rather to point out how singing and music began to change post-abolition. Most of the new recordings of spirituals we hear have been rearranged for choirs, in a hymn-like style that mixes Bachian choral harmony and gospel syncopation. Yet at the root of spirituals and work songs is this feeling of being able to overcome a seemingly insurmountable pain.

Eventually, the guitar and the piano became the weapon of choice for a new crop of singers who would combine both the secular and the spiritual into a new genre that would change the world…

The Blues

The blues is often oversimplified as a three-chord progression over which a blues scale melody is improvised on either an electric guitar or harmonica. (For a deeper exploration into the blues, check out Soundfly’s free online course, A Conversation with the Blues, which traces the through-lines of the blues in jazz, improvisation, rock ‘n’ roll, and even modern American poetry.)

The blues truly represents the transition from African slave to African American citizenry.

The blues was the soundtrack of those who, in the midst of this newfound freedom, struggled to define themselves within the aftermath of slavery, the industrial revolution, and the birth of a new form of slavery: Jim Crow.

One element that differentiates the blues from its predecessors is that it’s inherently more complex. For the first time in their history in America, African Americans had leisure time to sit and think deeply and critically about life, as well as learn instruments. In fact, it is the influence of instruments such as the guitar, banjo, piano, and various brass instruments that spawned a new sonic language for African Americans. Using various techniques like slides, trills, and bending notes, blues musicians were able to get their instruments to sing with the same inflections as a vocalist.

In poet Amiri Baraka’s groundbreaking book, Blues People, he states that the blues in its primitive form is without a definitive structure. Over time, though, the added definition, structure, and wider instrumentation allowed the blues to evolve in a way that started to make it digestible for more mainstream American audiences. This classic early blues style was popularized in the American mainstream by artists such as Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and countless others.

One element that makes blues music so effective is the blues scale and its functionality. Most early blues songs were in major keys featuring mostly major and dominant chords. The blues scale superimposes a minor pentatonic scale over a major key, with the addition of a very important note: the raised fourth, or sharp eleventh. This note adds chromaticism to melodic ideas and creates tension within the home key.

Therefore, both musically and metaphorically, the blues represents an unorthodox juxtaposition of ideas, which is arguably reflective of how the African American experience fits into American society as a whole.

Modern Innovations

As I previously mentioned, Congo Square in New Orleans is a very important site in regards to the evolution of American music. On Sundays, the slaves were allowed to play their drums during worship services and even for themselves. Gatherings in Congo Square provided the perfect environment for drummers of various backgrounds to share ideas and eventually incorporate European instruments. This sparked the rhythmic catalysts for what would eventually become dance-based musical forms such as ragtime, the boogaloo, the backbeat, and the shuffle.

The African thread throughout American music can be most notably traced through rhythm. As the blues migrated throughout the country and began affecting the way Americans rethought song form, singing styles, and storytelling, the rhythms began to shift and permeate American music in other ways, slowly giving way to new styles such as rhythm and blues, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, funk, and gospel. Syncopation, riffing, blue notes, and call and response are all elements of African music that have permeated the American mainstream, thanks to the ingenuity and “kitchen-sink” musical mentality of African Americans during and after slavery.

But as these various musical forms that derived from slave songs started to develop and become integrated into larger artistic contexts, they were swiftly abstracted from their original source. Hip-hop is the latest derivative of slave songs. In hip-hop’s foundational years, the music being created was a reaction to disco. Hip-hop stripped away the musical frills of disco and left just the drums and an emcee talking over the beats. This represented a return to the elements that made up the earliest forms of African American music: drums and voices.

Today, as music continually evolves and transforms, there are artists who have sought to draw inspiration from the earliest relics of the African diaspora. In particular, two New Orleanian trumpet players have released projects within the last couple of years that focus on connecting different elements of the African diasporic tradition with innovations from electronic music (drum machines, sampling, the use of effects, etc.). Those are Nicholas Payton’s Afro-Caribbean Mixtape and Christian Scott’s Centennial Trilogy, which includes songs like “Ruler Rebel,” “Diaspora,” and “Emancipation Procrastination.”

In the realm of hip-hop, artists such as Kendrick Lamar, Childish Gambino, and Common have all recently released recordings that speak, much like the blues, directly about the conditions of African Americans, while drawing sonically from elements of jazz, funk, and gospel.

Unfortunately, new forms of slavery still exist in a world that, although modern and vastly more tolerant, is still deeply flawed, unequal, and cruel. The number of men, women, and children considered to be locked in modern forms of slavery or unjustly imprisoned today is estimated at 40 million. Imagine a world where 40 million people could contribute to the world from a space of equality rather than bondage. It is this hope of a better world that gives spirituals, work songs, and the blues a power that perseveres through the most difficult times.

As we remember the history of slave songs and their plentiful musical offspring, it’s important to honor and respect that these genres are not simply subsets of musical variation, but relics of a culture born out of the cruelty of slavery. Because when you don’t honor the culture and history of a musical genre for its past, there’s a chance you might end of up creating a work like SLĀV.

To dig deeper into the music referenced in this article check out my playlist below.

!["The Old Plantation (Slaves Dancing on a South Carolina Plantation)" [ca. 1785-1795].](https://flypaper.soundfly.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/slavery-header-1024x683.jpg)