+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

I am fascinated by the creative potential of “musical theology,” a pre-Enlightenment relic from the tradition in which J.S. Bach thrived. For Bach and his cronies, music theory was a direct extension and reflection of metaphysical and religious truths. The major chord, three notes in one sound, was the trinity; equal temperament (a practical approximation that detunes each note slightly from the mathematical ratios of just intonation) represented the sinning imperfections of humankind, a musical Fall from God-made purity.

As the Enlightenment gathered steam toward the end of Bach’s life, such views seemed to many of his colleagues to be outmoded or even a threat, as the product of the very same ancient, superstitious religion that the Enlightenment sought to escape. (There is an amazing book about Bach’s encounter with Enlightenment attitudes if you wish to learn more about this.)

Writers like Scheibe attacked Bach’s in-depth use of musical theology, along with his general style, accusing him of “too much art.” Writing in Bach’s defense, his friend Birnbaum countered that “God is a harmonic being.” For Bach, composing was “not an act of free creation but… imaginative research” leading to a “musical science that seeks ‘insight into the depths of the wisdom of the world’” (Wolff, Bach: The Learned Musician).

The U.S. was founded on Enlightenment principles, and many of our deepest assumptions about art and life come from the era after Bach’s lifetime. Although Bach’s music is universally loved now, the stern Lutheran beliefs that infused its creation are counter-cultural today, and have often been ignored or derided since his lifetime. These days, the idea that theology can find direct expression in music theory can seem at best a heady curiosity, and at worst a regression to a way of conceiving the world whose very nature challenges some of our most cherished cultural, social, and political achievements.

In 20th and 21st century music there is a lot of imagination and experimentation, and strong interest in spirituality in general. But there isn’t much of this kind of intimate interweaving of specific sounds with concrete theological symbols. Composers like James MacMillan are exploring this sort of theology-based musical practice, as one writer describes his work, “giving the symbols and signs of Christianity their own flesh-and-blood physicality.” Others like Arvo Pärt use related methods in a broader sense. And surely there are other creative musicians working in this vein today.

“Reviving these older creative methods and conceptions of music makes a worthy and profound experiment.”

And yet, for the most part, it is a foreign way of thinking to our own: Much religious meaning in music today is practiced, and heard, as an all-encompassing, multi-faith spirituality rather than this Baroque-era sense that more specifically imagines “theology heard as sound.”

I often wonder what would happen if we bring back more of this kind of multilayered, allegorical thinking, this juicy stuff that made the music of Bach and others so meaningful in its day? Reviving these older creative methods and conceptions of music makes a worthy and profound experiment.

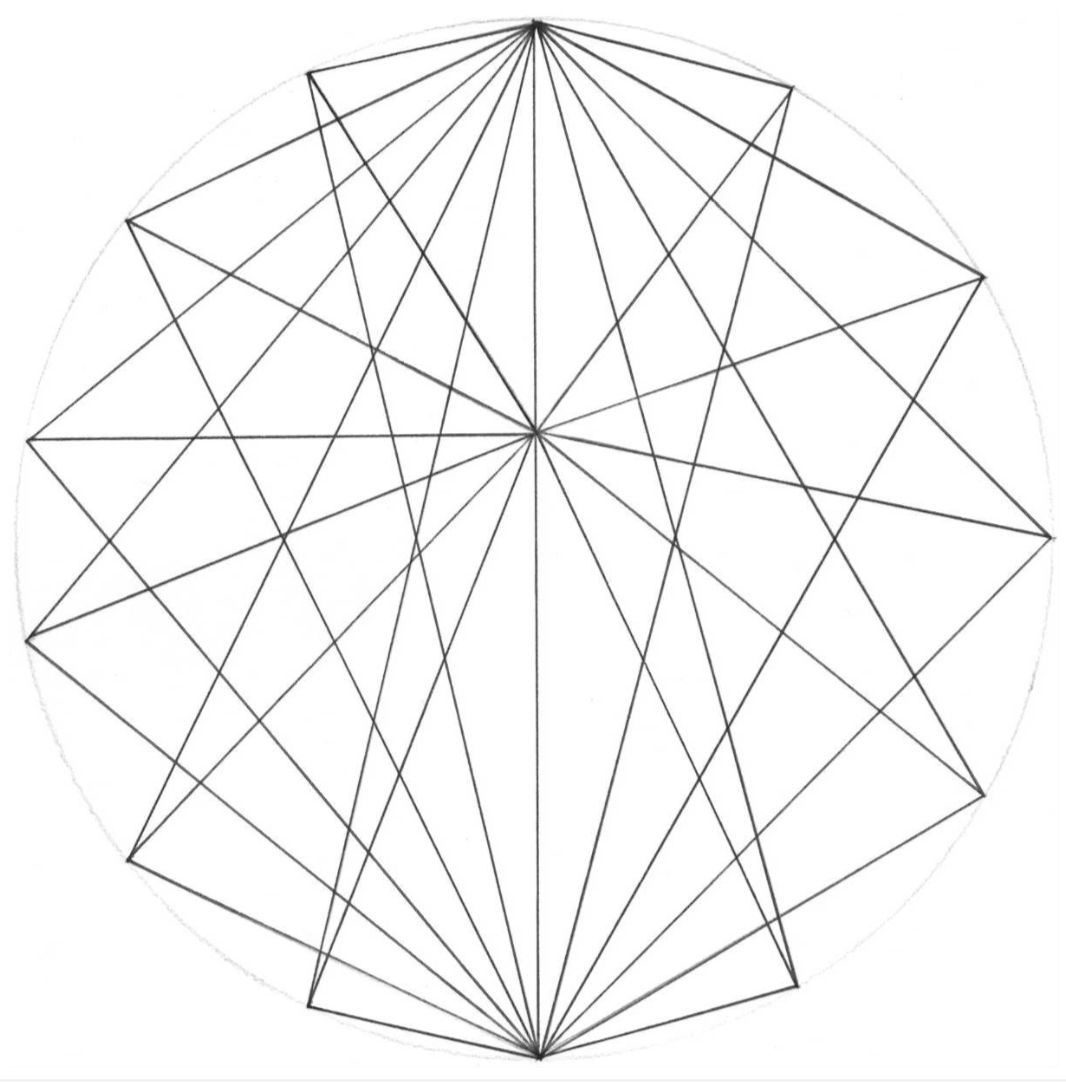

In my 2008 piece for Greek Byzantine choir and strings, Nativity Kontakion, I discovered a beautiful harmonic structure based around the Byzantine whole step you get when you divide the octave into fourteen 72nds — a bit wider than the whole step on the piano, which is twelve 72nds of an octave wide. Invert that wide “14/72” whole step, and you get a minor seventh narrower than the usual one. It so happens that this narrower minor seventh is almost equivalent to the seventh partial — one of those pure, God-made mathematical ratios that fell out of favor when equal temperament took over.

From this basis, I arrived at an elegant system of harmonic possibility that allowed me to compose music in an entirely new tuning system. I discovered rather than created this system, through a Bach-inspired process of “imaginative research,” infused with musical-theological connections in the spirit of Baroque metaphysics. For example, my use of the seventh partial mirrors and supports the subject matter of the Christmas/Nativity-themed text of the piece — according to Andreas Werckmeister, an organist and one of the main Baroque-era theorists of this system:

“The introduction of the first dissonant tone (the seventh partial), signifies that in this life some ‘dissonance’ must be mixed in; the number seven represents the totality of heaven and earth together” (Chafe, Allegorical Music).

So it’s a direct embodiment, in sound, of the theology of the Nativity: a baby who is both human and divine.

A more recent experiment with the same harmonic structure was my 2015 piece Territories, commissioned by What a Neighborhood! and premiered by the viola da gamba quartet Parthenia. The piece undertakes a spiritual journey from “our” world of the everyday, symbolized by conventional piano-like tuning in the first movement, through a murky in-between harmonic world in the second movement, and finally to a place of “otherness” in the third movement, which undertakes three modulations up through one of those wide whole steps to arrive at the interval of a fifth above, rather than the tritone that would occur in conventional tuning.

It’s a musical world that’s been bent, just a little, to reveal new horizons.

So, as you can see from these experiments of mine, I believe that this line of inquiry can help retrieve powerful and beautiful ideas from a venerable worldview that is strange to us, having gotten the short end of Enlightenment thinking. I think this perspective can ground us in deep cultural roots, offering us immense creative potential for our current moment, and I’m curious to see what others working in this capacity will bring to the table in the future! Perhaps it’ll be you.

*This article is adapted from my presentation at the conference ‘James MacMillan and the Musical Modes of Mary and the Cross’ at Notre Dame University, September 2012.

Improve all aspects of your music on Soundfly.

Subscribe to get unlimited access to all of our course content, an invitation to join our members-only Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever you want, with total freedom.

—

Robinson McClellan is a composer, writer, and teacher. His music has been performed, commissioned, and published widely. He has done artist residencies at MacDowell and Yaddo and earned his doctorate in composition from Yale. He works in product development, user care/feeding, and instructional design for music and education companies. He founded and directs ComposerCraft, a workshop for young composers.

Robinson McClellan is a composer, writer, and teacher. His music has been performed, commissioned, and published widely. He has done artist residencies at MacDowell and Yaddo and earned his doctorate in composition from Yale. He works in product development, user care/feeding, and instructional design for music and education companies. He founded and directs ComposerCraft, a workshop for young composers.