Welcome back to our new series on Flypaper, Album Histories Monthly, which brings you the story of a single album each month, in the month that it was originally released. Last month, we covered Joan Jett’s I Love Rock ‘n Roll. This month:

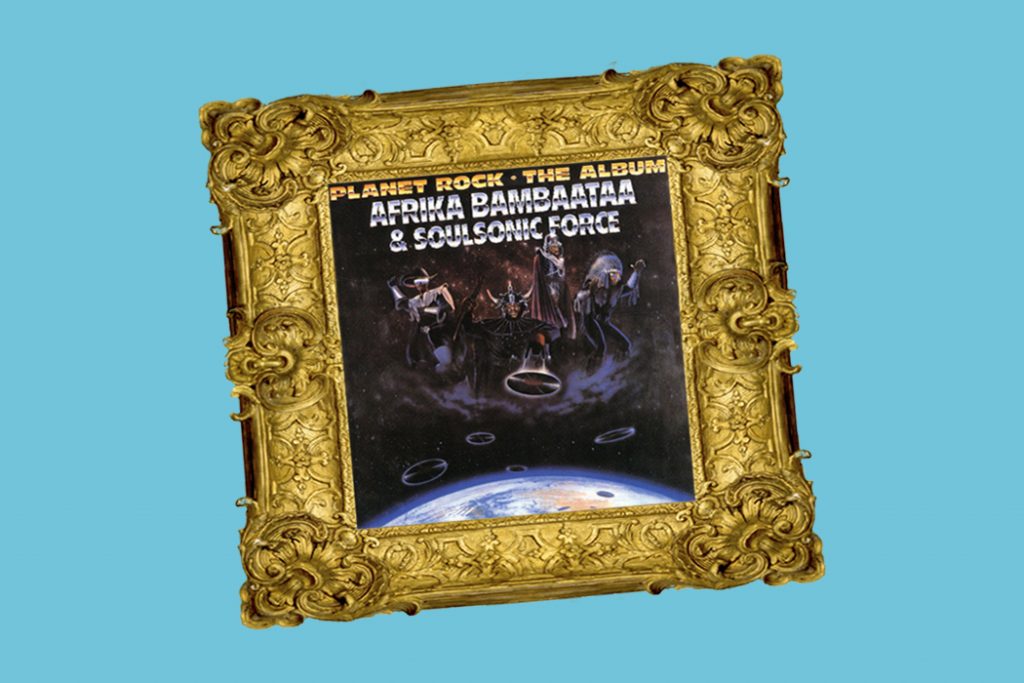

Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force – Planet Rock

Release Date: December 1, 1986

“Back then there was no such thing as hip-hop.” – Arthur Baker (producer)

Afrika Bambaataa’s (born Kevin Donovan) name was already synonymous with hip-hop culture long before he released his watershed 1986 album, Planet Rock. He was one of the first artists to combine the four pillars of hip-hop — rapping, DJing, breakdancing, and graffiti — into a united culture. With Bambaataa’s help, rap grew from an amorphous group of creative people living and communing in the Bronx in the 1970s, to a galvanized movement in the 1980s.

He was also a force of positivity, creativity, and pride for his community. His achievements outside of his music could have guaranteed him a place in the annals of music history, but his music has also proved to be timeless. Planet Rock blended European electronica and New York hip-hop to create something stunning.

Afrika Bambaataa burst onto the Bronx hip-hop scene in the early ’70s as a talented breakdancer and gang leader. His gang, the Black Spades, was mostly disbanded by 1973 but they continued to come watch him DJ at Bronx community centers, and a trip to Africa inspired Bambaataa to become a more positive force in his community.

He formed a performance group named the “Bronx River Organization,” which he renamed “the Organization” shortly after. Around 1974, he reorganized the Organization and renamed it again to the “Zulu Nation,” inspired by his studies about African history at that time. He was notably “impressed by the Zulus because they fought with full honor and simple weapons against the colonialism power in spite of apparent inferiority.”

Bambaataa was further inspired to establish hip-hop as a positive force when his best friend was killed in ‘74 as part of a gang war. He saw hip-hop as an alternative to the gang activity and drug-related violence. His lyrics on his debut album, Planet Rock, echo this sentiment. Shortly after this, he saw DJ Kool Herc and became convinced that his path lay in making hip-hop music. The Zulu Nation became involved with throwing parties and events where Bambaataa talked about hip-hop and spread a message of nonviolence.

He was signed to Tommy Boy Records in 1982 and released his debut single, “Jazzy Sensations.” “Back then, there was no such thing as hip–hop,” says Tommy Boy producer Arthur Baker,

“It was basically just rapping over beats, and most of the beats that people used were either from disco tracks or funk tracks. There was no segregation between disco, funk and rap. It was called rhyming. People were just rhyming over breaks.

The first time I heard rappers was up in the Bronx where people were in the park, talking over records. [Latin R&B artist] Joe Bataan had told me about them, and he was like, ‘Man, someone’s gonna make a million dollars on this.’ I, myself, certainly thought it was interesting stuff. You know, I didn’t laugh at it, because I was all about finding out what was happening on the streets.”

This was the beginning of a new era of commercially viable hip-hop, paved by groups like RUN DMC, Eric B. and Rakim, and Whodini, all making a name for themselves. No artists, however, were experimenting with exciting studio production techniques as much as Afrika Bambaataa.

Planet Rock was recorded at the then-unknown Intergalactic Studios over the course of about five years. Intergalactic Studios would later be made famous by the Beastie Boys, but in the mid-1980s, it was relatively unknown. Bambaataa recorded the album single-by-single, and eventually compiled all of the sides into a full-length album released in 1986. The studio itself was also very simple. “It wasn’t like they had walls of outboard gear and walls of keyboards,” Baker remarks,

“They only had a few things, and so we basically got all of our effects out of the Lexicon PCM41, including Bambaataa’s electronic vocal vocoder sound.”

The electronic elements on Planet Rock are so bold that it’s hard to believe they pretty much all came from a single unit. The PCM41 was one of the first digital delay boxes that were commercially available. Like most of the early delay units, the 41 provided modulation effects (chorus, flanging, etc.) by varying the sample rate of the device. And despite that this device came out as far back as 1980, you can still find it in studios everywhere, ready to add flare to mix, thanks to its versatility, sonic clarity, and resourcefulness. It’s a testament to the quality of the design and manufacture of these devices.

“We’ve made musical history tonight.” – Arthur Baker

While their setup was relatively simple, the sound of the album is far-out, complex, and almost other-worldly. Keyboardist John Robie was the missing link between simple, solid equipment and that crazy Afrika Bambaataa sound. Producer Arthur Baker said, “Bambaataa wanted to use the keyboardist who had played on a record that he liked, and this turned out to be John Robie, who is now my oldest friend. John played everything by hand, nothing was sequenced on Planet Rock — we didn’t have a sequencer at that time.”

One of the most enduring influences Planet Rock left on hip-hop was the pioneering use of the Roland TR-808 drum machine. According to The New Yorker, “Afrika Bambaataa’s implementation of Roland’s magic box was indisputably the Big Bang of pop’s great age of disruption, from 1983 to 1986. The 808’s defiantly inorganic timbres — robot handclaps, turn-signal cowbells, a compressed-air punching snare.”

The TR-808’s influence on beat making can be seen all over hip-hop from Kayne West’s album 808s and Heartbreak to Blaque’s banger “808.” It has become a ubiquitous part of hip-hop production and is used in many songs today.

The recording of Planet Rock went smoothly and quickly. The greatness of the album was self-evident, and Baker knew it immediately. He said:

“When I took Planet Rock home and played it for my wife, I told her, ‘We’ve made musical history tonight.’ I knew it. There wasn’t a doubt in my mind. From the start, I was definitely into the record being a merging of cultures, and I said, ‘We’ve done what Talking Heads have been trying to do, but our record is going to sell uptown and downtown.’

Working in a record warehouse, I was really educated as to what people on the streets were buying, and whenever I heard ‘Numbers’ being played at the Music Factory in Brooklyn, I saw black guys in their twenties and thirties asking, ‘What’s that beat?’ So I knew that if we used that beat and added an element of the street, it was going to work.”

Everyone involved believed the album would be a success. The single, “Planet Rock,” didn’t make the Top 40 but did reach number four on the R&B charts, certifying it as a true hip–hop classic. This also primed Bambaataa’s new audiences for his next single release, “Looking for the Perfect Beat.”

As for the longevity of the musical ideas on the album, well, they continue to permeate hip-hop today. The incorporation of electronic and synthesized elements, wild breakdowns, arhythmic vocalizations, and, of course, the iconic timbre of the 808 kick can be heard on the radio today almost every time you turn the dial. Even specific trends in beat making, such as using handclaps instead of a snare, find their origins hidden deep inside this album.

“Planet Rock” certainly deserves its number-three spot on Rolling Stone’s “Greatest Hip-Hop Songs of All Time.” As Rick Rubin said:

“It changed the world.”

Interested in learning more about pro-audio mixing techniques? Preview our Faders Up: Modern Mix Techniques course, which combines tips and perspectives from nine of today’s top sound engineers along with professional mentorship on your work for six weeks from a Soundfly Mentor, for free today!

Sign up for our On the Fly newsletter to receive exclusive discounts on current and forthcoming courses!

—

Bibliography

“50 Greatest Hip-Hop Songs of All Time.” Rolling Stone, 5 Dec. 2012. Web.

Burger, Remy. “The Culture.” Spartanic Rockers. Web.

Buskin, Richard. “Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force: ‘Planet Rock’.” Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force: ‘Planet Rock’, Sound on Sound, Nov. 2008. Web.

LaSalle, Gordon. “Lexicon PCM-41 Digital Delay Processor | Gordon LaSalle Music.” Reverb.com. Web.

Norris, Chris. “The 808 Heard Round the World.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 13 August, 2015. Web.