+ Bridge the worlds of theory, improvisation, and jazzy hip-hop, and improve your piano chops with Grammy-winner Kiefer in his course, Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.

Jazz music is daunting to wrap one’s ears around. It is safe to say most Americans have a complicated relationship with one of our oldest art forms. Jazz is chronically misunderstood, mislabeled, and hardly given the attention and respect that it deserves. Most people have some idea already formed in their head of what “jazz” is. For some, it’s classic singers like Sinatra or Tony Bennett.

For others, it’s the early instrumentalists like Louis Armstrong or Coleman Hawkins. For some, it’s a band they heard noodling in the background at a restaurant, and for others it’s something to tune out at a cocktail reception.

The truth is: jazz is all of those things, and much more. Jazz is complicated because it is inherently difficult to understand, and it challenges its listeners almost as much as it does those who choose to learn to play it. Once upon a time, jazz was America’s popular dance music; however, its position in our culture has shifted.

On one hand, jazz has become hyper intellectualized and esoteric, appealing to clove-smoking, turtlenecked beatniks and their coffee-obsessive hipster offspring. While on the other, it’s been neutered and stripped of its soul by new wave crooners and smooth instrumental covers doomed to dwell in hotel lobbies.

Jazz music first caught my ear a few years into my musical training. I had been in my high school jazz program, but I was never intrigued until the idea clicked that for a guitarist like myself, jazz presented a unique challenge of weaving through chord changes and learning a complex new musical vocabulary. This began a love affair with analyzing harmony, melody, and rhythm that I carry with me even through today. And as I listen to more and more artists in the realm of popular music, the more I notice how vast an influence jazz has had on other styles of music around it.

Here are just a few examples of songs that draw some of their definitive characteristics from the patterns, movements, and cultural stylings of jazz music — be they harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, or some combination of all of those things. Strap on your fedoras, folks!

By the way, if you’re interested to learn more about how to harness the intersections between jazz, improvisation, and modern music like hip-hop in your own music, you’re going to love Soundfly’s newest course with jazz pianist and beat producer, Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.

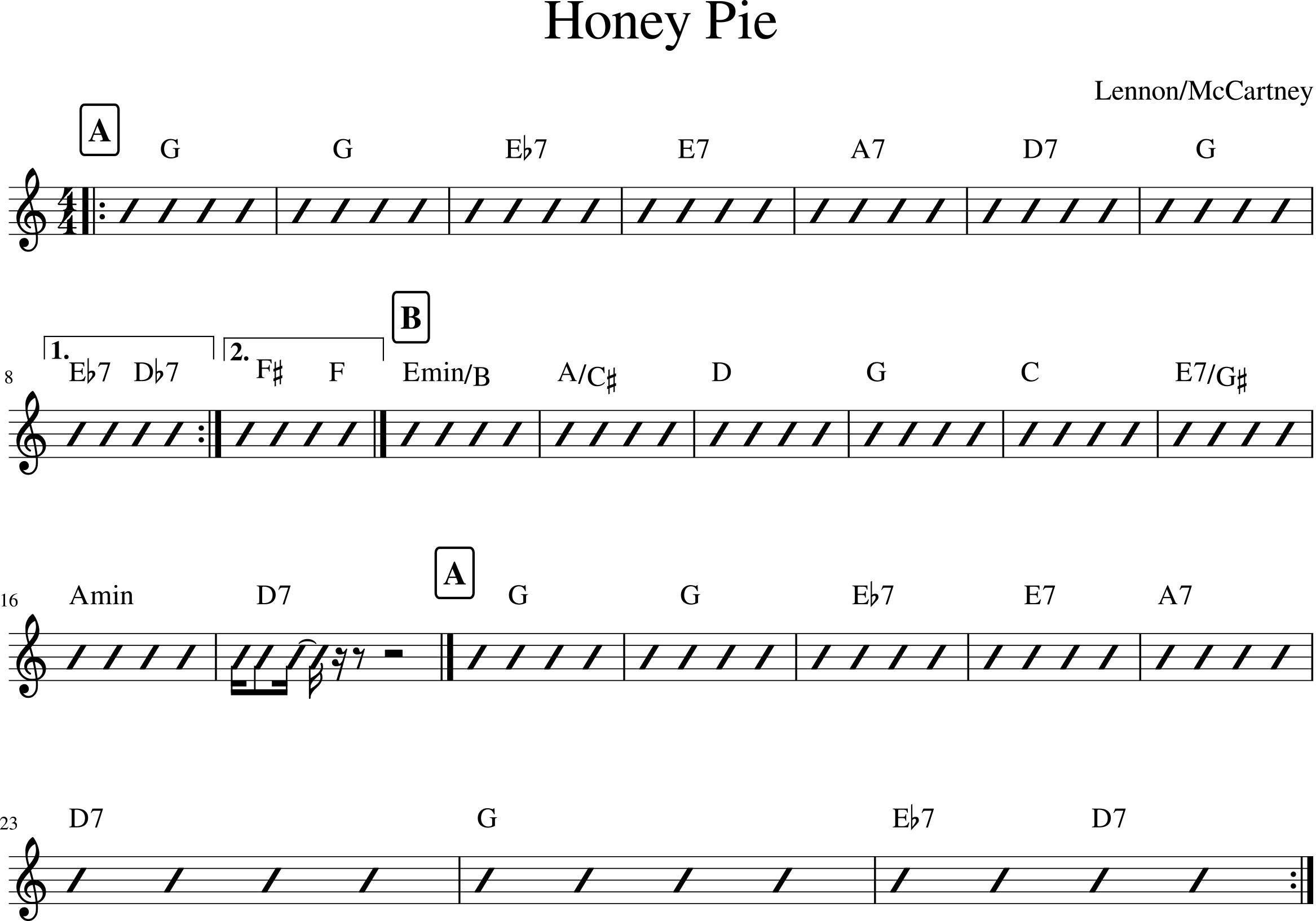

Honey Pie (Lennon/McCartney)

There is absolutely nothing subtle about the jazz influence in this song, which makes it a perfect place to start. “Honey Pie” is actually an homage to British “music hall” entertainment — not a far stretch from American vaudeville of the early 20th century. But stylistically, this Beatles’ song from the White Album borrows from the big band swing sounds of like bands led by Billy Eckstine or Duke Ellington.

After a brief introduction, the song follows an AABA form. That’s a crucial structure in jazz music, and is important because the AABA form isn’t seen as often in modern pop music, which relies mostly on verse-chorus-verse-chorus forms (ABAB). Many of McCartney’s songs reject traditional pop songwriting formats in favor of those seen in jazz, like AABA, or ABABC, or really anything that isn’t verse-chorus-verse-chorus. For now, let’s discuss recognizing the AABA form.

We are looking specifically at the harmony and melody, and not so much the lyrics or any background figures. The first 8 bars of the song (which is in G) are the same as the second 8 bars! Well… almost the same. The difference is in the very last section of the second phrase. That subtle shift exists in order to facilitate the transition to the third set of 8 bars, which is notably different than the others.

Starting to see the big picture? That third set of eight bars eventually brings us home to the original thematic material, thus completing the form. So if we call the first eight bars “A”, which repeat, and that third set of eight bars “B” (because it is a different harmony and melody), then the pattern is AABA.

This pattern is used in countless jazz and swing standards that are still often performed today. In addition to the swinging clarinet backgrounds, the harmony, which shares common ground with Thelonious Monk’s tune “I Mean You,” and the laid back feel, it’s hard to ignore the influence of jazz music on this particular Beatles song.

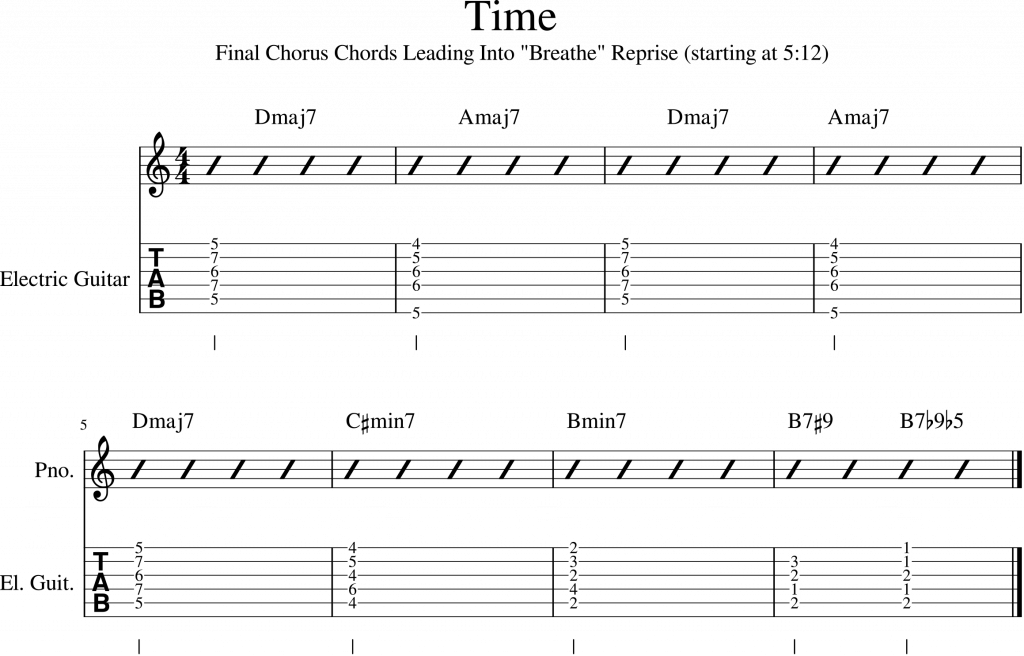

Time (Pink Floyd)

There is an abundance of jazz influence in classic rock music. Look no further than The Doors, Led Zeppelin, and Jimi Hendrix and you’ll find it. But let’s look at the way “Time” employs harmony and chordal changes as well as the meticulously crafted guitar solo.

The chords used are a mix of major 7th chords, minor 7th chords, and dominant 7th chords with extensions such as the ♭9 and ♭5. In order to form a chord, we must start with our root note, followed by a third (which gives it a major or minor sound), and a fifth (which stabilizes the root). Extensions, like the 9th, 11th, and 13th are all additional colors that are most often found in jazz music.

The way that David Gilmour solos through these chords makes use of what we call “leading tones.” Leading tones are the descriptive elements of each chord, such as the 3rd or 7th, that illustrate the essence of what those chords have to offer. It’s important to think of those specific sounds when navigating through tougher harmonic stretches because as an improviser, they offer a wider palette than simply floating over the harmony. Jazz musicians learn to use leading tones to improvise because of the tricky chord changes that many jazz compositions employ.

So, while most people weren’t aware of it, David Gilmour was waving a crucial jazz concept right in front of our noses in one of the most celebrated guitar performances in rock history!

There is also the matter of structure. “Time” begins unusually, with about 30 seconds of ringing clocks, followed by almost two minutes of a percussion solo performed on rototoms over a thematic overture of the chords in the song. Finally, we have our first verse, and then the chorus, which are immediately followed by a guitar solo that lasts for a minute and a half. Then our final verse and chorus, which paves the way for a reprise of a theme heard earlier on the record. This lofty framework is far from the constrictions of traditional pop, and while not exclusively a jazz concept, I would cite it as an influence.

Believe (Q-Tip feat. D’Angelo)

Hip-hop and jazz have long been intertwined, and share many common traits. The influence of jazz on the formation of hip-hop cannot be overstated. From its humble beginnings as sample-based party music, hip-hop has developed into its own culture, and currently holds influences on every conceivable aspect of the music industry — including jazz!

Hip-hop producers have long used the process of sampling to create brand new music. In some cases, the sampling is overt, and the original works are clearly heard. In other cases, the producers will flip samples on their head, layer different elements, chop and rearrange, and truly exercise creativity in ways that can be described as genius. From early pioneers like Gang Starr, De La Soul and Digable Planets to wizardry of the late producer J Dilla, jazz music has long been used in hip-hop to create some of the most influential music of the genre.

I chose the song “Believe” by Q-Tip because it features a turnaround. In jazz music, turnarounds are a series of chord changes that lead us from the end of a form or section and back to the top of the form. Often, the turnaround in a jazz composition might use non-functional harmonies, i.e. chords that really don’t have much to do with each other when analyzed. When those turnarounds are isolated, in this case if they’re sampled and looped, they give us a fresh, new harmonic landscape to work with.

Here is Tadd Dameron‘s tune “Lady Bird” (written in 1939), which is often credited for popularizing the turnaround for many jazz tunes to follow it. Listen at 0:30 for the first time it appears as a transition phrase, and you’ll notice how similar the chord voicings are to Q-tip’s looping progression.

Q-Tip’s former group A Tribe Called Quest was on the foreground of the jazz/hip-hop movement, and here, in the case of this album The Renaissance, he is assisted by two modern jazz legends, keyboardist Robert Glasper and guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel. Songwriter and producer Raphael Saadiq also lends his hand, performing the bass part.

Q Tip raps over the groove with the rhythmic confidence and phrasing of an instrumental soloist, rhyming over bar lines and emphasizing particular words and phrases. The hook, sung by the dark wizard of R&B, D’Angelo, is simple, but in his multi-layered vocal style. Truly this is a jazz rap classic.

Don’t stop here!

Keep learning about theory and harmony, composing and arranging, songwriting, and more, with Soundfly’s in-depth online courses. Subscribe for access to all, including The Creative Power of Advanced Harmony, Orchestration for Strings, and our exciting new course with Grammy-winning pianist and producer, Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.