+ Our brand new course with The Dillinger Escape Plan’s Ben Weinman teaches how to make a living in music without making sacrifices. Check out The Business of Uncompromising Art, out now exclusively on Soundfly.

If you’ve spent enough time around guitarists or bassists, you’re certainly familiar with what gear obsession looks like. You may even be a gear obsessive yourself, or have at least been through a phase of quarreling over minutiae in online fora. And if you know a gear obsessive, you’ve almost certainly witnessed them debate their main adversary: the “tone-is-in-your-fingers” contrarian. You may have survived this phase as well — some players even manage to be both at the same time (a condition usually marked by more than a trace of self-loathing).

Gear obsessives have a rigorous dedication to the idea that everything in their rig must be perfect. They’ll poeticize the sound of a single-coil with just the right amount of wax potting (not too much, not too little!), or lament that Deluxe Reverbs never sounded the same after Fender switched from the blue Mallory coupling capacitors to the no-name reddish-brown ones.

“Tone-is-in-your-fingers” contrarians scoff at gear obsessives. They maintain, with a touch of obligatory condescension, that “you will sound like yourself no matter what, because your tone is in your hands.” To them, obsessing over gear is pointless and tedious; clearly a player’s time would be better spent practicing.

Both are right, both are wrong, and both are missing a fundamental point.

When good tone is the goal, technique and gear are both secondary to musicianship — listening, specifically.

The basis of “good tone” is understanding, in real time, what sounds are possible in a given situation and how to contextualize them in a meaningful way. It’s a connection to the instrument that moves beyond its mechanics and toward an ability to make it “sing.” Good tone is neither something you buy nor something you achieve — it’s something you learn to do. It’s a real-time activity.

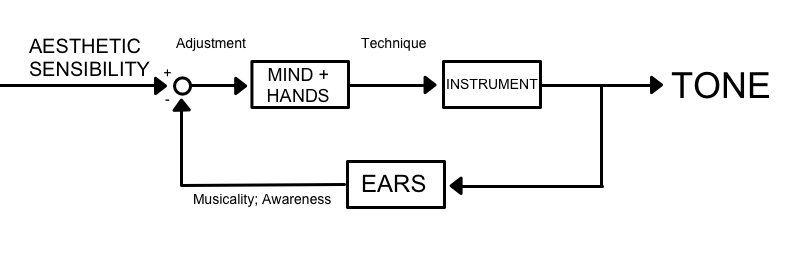

On a holistic level, the player’s ear, mind, hands, and instrument collectively form what an engineer might refer to as a feedback control system. What this means is that you, the player, have the ability to constantly compare what you wish to happen with what’s actually happening, and to make real-time adjustments to try and make them match. As we gain experience performing, we hone the active precision of this system. All of the little subconscious adjustments — the moves our mind instructs our hands to make in response to what we hear — become more reflexive, intuitive, and automatic.

But that’s still only part of the story, because even the most perfectly tuned feedback control system needs a reference to compare against. The standard by which your mind and ear will judge all of its sonic input is the aggregate of all your listening experience, playing experience, life experience, and good taste.

So while the gear and the hands do matter (and the ear and the mind matter arguably more), your tone will also depend on how you handle — in ways both conscious and subconscious, both premeditated and instinctual — fundamental aesthetic questions like “what is beauty?”

It will depend on your ability to recognize cultural signifiers and make determinations about context. It will depend on your ability to recognize group balance and dynamics; to comprehend how your sound is strengthening or weakening (or being strengthened or weakened by) other voices within the group; how it frames the lead or is framed by the rhythm section.

It will depend on your ability to parse room acoustics and predict how they affect your sound’s translation in the house, and to some degree on your understanding of the instrument’s role throughout music history (and on your desire to adhere to, extend, or subvert that role).

Most importantly, it will depend on the way your individual subconscious processes all of this in real time, as you play.

It goes without saying that no amp or pedal holds answers to those questions. But neither does technique. Those are aesthetic sensibilities. The extent to which they emerge depends on your intuitive, experience-based ability to channel them. When a great player gets a beautiful sound out of a subpar rig, the common assumption is that his or her technique is somehow overcoming the rig’s weaknesses and shining through. But the truth, more often, is that the player is recognizing, within the rig’s limitations, sonic possibilities that another player might miss. Those possibilities can then be explored and used to their best advantage.

Moreover, great players’ distinctive aesthetic identities will shine through regardless, and that’s almost always where their real magnetism originates. It’s very common to hear a player with great energy or an ebullient musical personality erroneously described as having great “tone.” But show me a “bad” tone, and I’ll find you a player who could turn it into a strength with a superior vision and a keen ability to reshape context.

A player’s sound is inextricably linked to every single aspect of musicianship he or she has acquired over an entire career. There are no meaningful shortcuts. As with so many other aspects of musicianship, the best way to refine the skill of tone (and it is a skill) is probably to just keep listening. Listen hard, listen easily, listen broadly, listen narrowly, and listen deeply.

Then react.

Rev Up Your Creative Engines…

Continue your learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, RJD2, Com Truise, Kiefer, Ryan Lott, and Ben Weinman’s The Business of Uncompromising Art.