+ Take your modern jazz piano and hip-hop beat making to new heights with Soundfly’s new course, Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production!

I tend to put off Western notation in my New School Fundamentals of Western Music class for as long as I can, but towards the end of the semester, there always comes a time when we simply can’t avoid it any longer.

As expected, most students are struggling with key signatures; this is understandable! Like the rest of the Western notation system, key signatures are based on a big assumption: that all of the notes will be within one of the twelve major keys, or within some scale that can be derived from a major scale (most often, the natural minor scale).

This assumption makes an awkward fit with the music that my students are making and listening to. Read on!

(*To understand keys, scales, and modes on a deeper level and how they can help your songwriting, preview instructor Ethan Hein’s online courses Unlocking the Emotional Power of Chords and Creative Power of Advanced Harmony on Soundfly).

Several students have asked me if there is some shortcut or mnemonic for memorizing the key signatures. The answer is yes; there are many, but I’ve never found any of them to be helpful. The only thing that worked for me was to learn, write, and improvise a lot of music in every major and minor key until they were as familiar as the layout of my apartment.

My method was slow, but effective.

You can think of music notation as a graphical representation of the white keys on the piano. The white keys play the seven notes in the C major scale, repeated across octaves. C major is Western music’s default setting. To play the other major scales, you will need to replace one or more white-key notes with one or more black-key notes. Each black key confusingly has two names:

- A-sharp/B-flat

- C-sharp/D-flat

- D-sharp/E-flat

- F-sharp/G-flat

- and G-sharp/A-flat.

In notation, you change a white-key note to its neighboring black-key note using a symbol called an accidental. If a note is always going to be sharp (♯) or flat (♭), you can save yourself time by writing the accidental right at the beginning of the piece, and it will apply to that note every time it occurs. This collection of “global” accidentals is called the key signature.

Some students have asked me why you even need key signatures. Couldn’t you just write accidentals next to all of your notes one at a time?

Sure you could! Bach wrote his famous “Chaconne in D minor” without a key signature, and put in the individual B-flats as they arose. That’s fine for D minor, but in other keys, writing all the accidentals individually would be too much work. Here’s a little tune I wrote in E major, shown in two ways: with accidentals on individual notes, and then with a key signature. You can see how the one-at-a-time method would get old fast.

Aside from convenience, the main reason to use key signatures is that they communicate to the performer what key the music is in, at first. If I see a key signature with four sharps, then I’m going to mentally prepare myself to play E major. If there’s no key signature, I don’t know what to expect, and that’s just more cognitive load for me.

You might reasonably ask why you can’t just write “E major” at the top of the page. In jazz, you sometimes do write the key verbally at the top of the page, especially if the tune is in an unusual mode or scale. But that’s not the conventional way to do things.

The sharps or flats that make up a key signature appear in a specific order. In the following section, I’ll explain how that order works for major keys. In classical music, major keys and major scales are the same thing, so that makes things conceptually easy. In more current music, the situation is more complicated, because major-key music is full of modes and blues and such, but we’ll get to that later.

A brief aside…

We recently launched a video on our YouTube channel that teaches any musician how to memorize every common note interval using only movie themes from John Williams scores. It’s…pretty rad. Musicians, composers, and curiosity-junkies, check it out and subscribe if you like that sorta thing!

Major Key Signatures

There’s an elegant and simple way to understand which sharps and flats you use to make the major scales. It involves the circle of fifths, which is one of those music theory things that you should just memorize, because it’s useful and it comes up a lot. Here’s the circle:

The key of C major uses no sharps or flats (it’s all white keys.) As you go clockwise around the circle of fifths from C, those key centers use sharps. As you go counterclockwise around the circle of fifths from C, those key centers use flats. When you get to the bottom of the circle, you have a choice to make. You can think of that key as being F-sharp, which you write with sharps, or as being G-flat, which you write with flats.

In the olden days, F-sharp and G-flat were actually two different keys using two slightly different-sounding sets of pitches. However, in the era of equal temperament, F-sharp and G-flat are perfectly interchangeable. So why do we bother maintaining both sets of names? Because it’s hard to change tradition.

This diagram shows you which notes you have to make sharp or flat to construct each major key signature. The notes are cumulative as you go around.

First, let’s think about the sharp keys.

To make the key of G, you change F to F-sharp. To make the key of D, you change F to F-sharp, and C to C-sharp. To make the key of A, you change F to F-sharp, C to C-sharp, and G to G-sharp. And so on. Are you noticing a pattern? The last sharp in the key signature is the leading tone (scale degree seven) of your key.

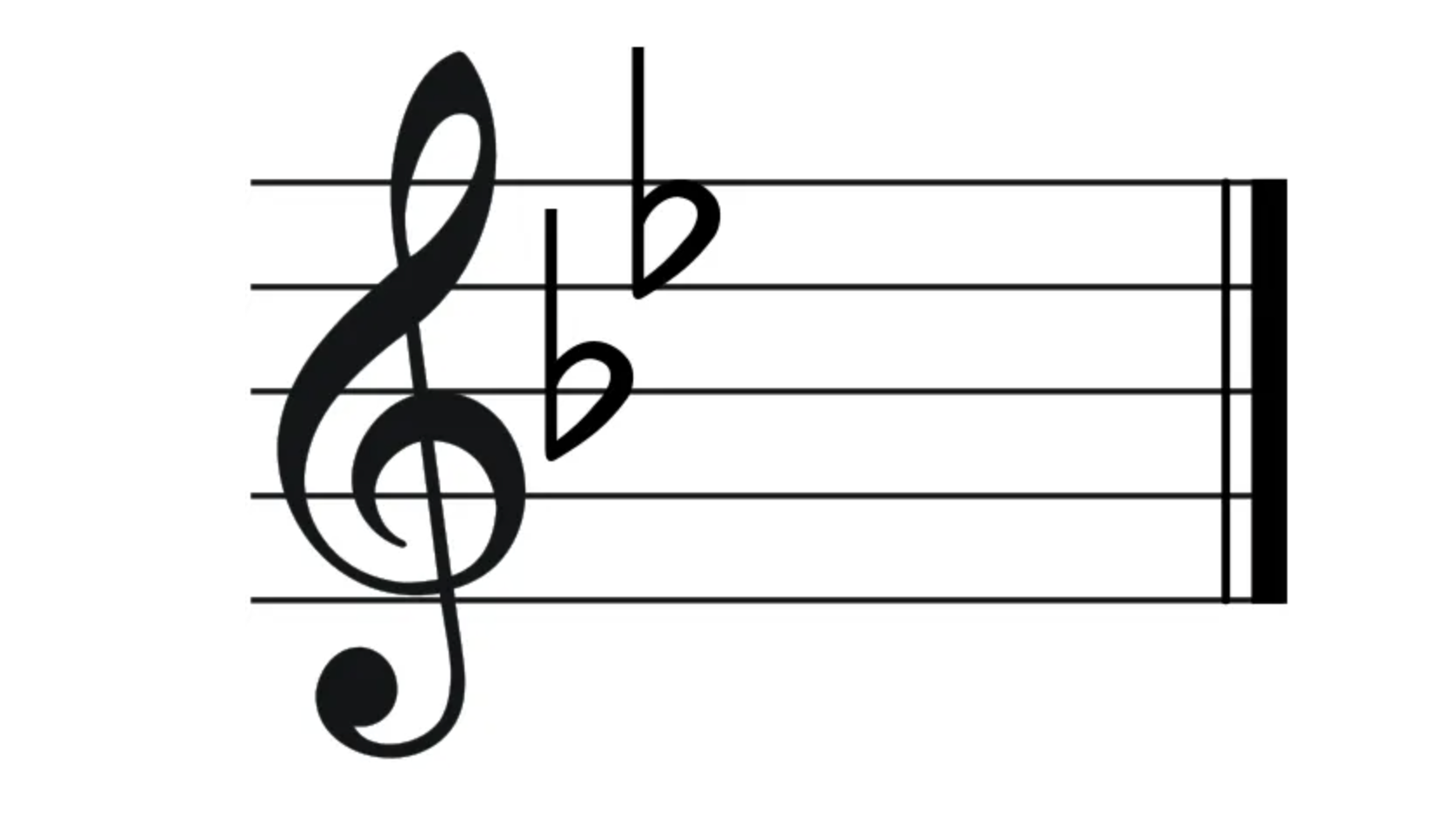

Now, let’s think about the flat keys.

To make the key of F, you change B to B-flat. To make the key of B-flat, you change B to B-flat, and E to E-flat. For the key of E-flat, you change B to B-flat, E to E-flat, and A to A-flat. The pattern should be clear here too: the last flat in the key signature is the subdominant (scale degree four) of your key.

Let’s think a little more about what it means to move from one key to another around the circle of fifths. Here’s another version of the diagram, showing each key center with its dominant chord (the purple ones). In classical music, you establish a key by playing that key’s dominant chord followed by its tonic chord.

To establish the key of C, you play a G7 chord followed by a C chord. To establish the key of E, you play a B7 chord followed by an E chord. To establish the key of A-flat, you play an E♭7 chord followed by an A♭ chord.

If you want to change keys in a smooth and logical-sounding way, a good method is to play the dominant chord in your new key and then resolve to its tonic. You can get from any key to any other key that way and it will sound okay, but it sounds especially good (to Western trained ears) if you move your key centers counterclockwise around the circle of fifths.

To move one step counterclockwise around the circle, you take the seventh scale degree of your present key and flatten it. For example, to move from C major to F major, you change B to B-flat. In classical music, you’d most likely put that B-flat on top of a C major triad, which changes it into a C7 chord.

In other words, you transform the tonic chord in C into the dominant chord in F major. Then you resolve to an F chord. Try it and enjoy the smooth sound of functional tonal harmony. If you then wanted to move from F major to B-flat major, you’d change E to E-flat. You could put that E-flat on top of an F major triad to change it to an F7, the V7 chord in B♭ major, and then resolve to B♭ itself. And so it goes.

This kind of counterclockwise circle-of-fifths key movement happens all the time in real-world music, and it sounds delightful.

It also sounds good to move your key centers clockwise around the circle of fifths. To do so, you need to raise the fourth scale degree of your current key to the excitingly dissonant sharp fourth. This sharp fourth becomes the leading tone in the new key.

Let’s say you want to move from C major to G major: you change 4^ in C to ♯4^, which is to say, you raise F to F-sharp. You’d most likely use that F-sharp that in the context of a D7 chord, the V7 chord in G major. To get from G major to D major, you change the 4^ of G major to ♯4^, that is, raise C to C-sharp. You’d probably put that C-sharp in an A7 chord, the V7 chord in D major. To get from D major to A major, you raise G to G-sharp and put it in an E7 chord, and so on.

Moving your roots this way is extremely common in canonical classical music, and is not uncommon in older pop and country styles. However, you typically don’t go multiple steps clockwise around the circle in sequence.

A few technical odds and ends: if there’s a flat or sharp on a particular note in the key signature, that means that note is also flatted or sharped in every octave. Also: I’m not going to talk about the more extreme sharp and flat keys where you need double flats and double sharps. If you’re at that level of sophistication, consult a music theory textbook.

Minor Key Signatures

Minor key signatures are harder on the brain than major keys, because they don’t really get their “own” key signatures. Instead, each minor key shares the same key signature as its relative major. So A minor has the same key signature as C major; E minor has the same key signature as G major; B minor has the same key signature as D major; and so on.

The logic behind this convention is that each natural minor scale contains the same pitches as its relative major scale, so you’re using the same sharps and flats.

You add your sharps and flats around the circle of fifths the same way you did in major.

In sharp-side minor keys, the last sharp in the key signature is on scale degree two. In flat-side minor keys, the last flat in the key signature is on scale degree six. If you are going to use the harmonic or melodic minor scales, you will need to manually stick accidentals on the individual sixth and seventh scale degrees as necessary.

Just like with the major keys, you often want to move through the minor keys around the circle of fifths. Moving counterclockwise is common, and is relatively easy to understand: you just change your tonic chord to the dominant on the same root, and then resolve it down a fourth.

To get from A minor to D minor, you just change the Am chord to A7, the V7 chord in D minor. To get from D minor to G minor, you change the Dm chord to D7, the V7 chord in G minor. And so it goes.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Three Scale Modes That Will Deepen the Emotions of Your Pop Song.”

Diatonic Modes

The key signature system comes from a time and place when it was assumed that everything was either in a major key, or in a minor key that mostly used natural minor. That system worked great in Western Europe for many hundreds of years. But tastes change, and we Western people in the present find the diatonic keys to be too plain-vanilla.

Pop music of the past hundred-ish years has been increasingly likely to use modes and blues to produce notes that are “outside” according to the rules of Mozart. Jazz and “art” music use all kinds of exotic and non-standard scales. All of this makes using standard key signatures harder and more annoying.

Let’s say you want to write something in a diatonic mode: Mixolydian, or Dorian, or Phrygian or whatever. The standard way to do key signatures for the modes is similar to the way you do it for natural minor. You figure out which major scale your mode is derived from, and you use the key signature for that major key. (*Soundfly’s got a short course series all about diatonic scale modes that you can access entirely for free here!)

So say you’re John Coltrane, and you’re writing a tune in D Dorian mode.

D Dorian has all the same pitches as C major, so you’d write a key signature with no flats or sharps. Now let’s say the bridge of your tune is in E-flat Dorian mode. That scale uses the same pitches as D-flat major, so you’d change the key signature to include B-flat, E-flat, A-flat, D-flat, and G-flat. Then when your tune went back to D Dorian, you’d switch back to the no-flats key signature for C major.

In classical music, this system for modes is fine, because the modes don’t really exist outside the context of the major/minor key system. When Beethoven wrote the third movement of his String Quartet No. 15 in “F Lydian,” he meant that it was really in C major, but that it hung around the F a lot.

So it made sense to write the key signature as C major. But that might give you the idea that everything in F Lydian is “really” in C major. When you listen to “Possibly Maybe” by Björk, most of the tune is in A Lydian mode.

It would be conventional to notate it using the key signature for E major, but then you might get the idea that the tune is “really” in E major, and it isn’t. For another example, Coltrane’s beautiful tune “India” is in G Mixolydian. The classical convention is to say, well, that means it’s “really” in C major, so you should use the key signature for C major. But “India” is obviously not in C major; the bass never moves off G for the tune’s entire fourteen-minute duration. So a key signature suggesting C major is illogical.

It might make more sense to notate modal tunes using the key signature for the parallel major or minor key, not the relative one. You could write your D Dorian mode tunes using the key signature for D minor, your G Mixolydian mode tunes with the key signature for G major, your A Lydian mode tunes with the key signature for A major, and so on. You’d have to correct a lot of individual accidentals by hand, but it would communicate more clearly to the player what key they’re really in.

In rock and pop music, you frequently combine a parallel major scale and Mixolydian mode, or a parallel natural minor scale and Dorian mode.

In those cases, it would be nice to not to have to put key signature changes all over the place. But the kinds of pop music that spend the most time outside the diatonic key system are usually not notated at all to begin with, so there hasn’t been so much urgency to get this system fixed.

The Blues

Talk about a music that exists outside the Western European major/minor system!

The usual way to do key signatures for the blues is to use the major key with the same root. So if you’re writing a tune in E blues, you use the key signature for E major, and then you’ll just have to write lots of accidentals on individual notes to make the various blues scales. This is extremely cumbersome! The good news is you rarely notate blues music anyway, so it probably won’t come up.

In case you’d like to learn a ton more about how the blues operates musically, Soundfly’s got a free course all about it! Here’s an episode from the course on the 12-bar blues.

Atonality and Exotica

What if you want to write using something more unusual? What if you’re writing with a diminished or whole-tone scale, or a non-Western scale, or some idiosyncratic collection of pitches that you invented?

There are two typical approaches. You can try to find some major or minor key that’s similar, and then use accidentals on individual notes. Alternatively, if there is no meaningful comparison to any of the Western keys, you can just have no key signature at all, and use accidentals on all the individual notes anyway. A few people have preferred to solve this problem by inventing custom key signatures.

For example, Béla Bartók liked to write in Lydian dominant mode. In C, that’s the pitches C, D, E, F-sharp, G, A, and B-flat. The standard method would be to use the key signature for C major, and then put sharps on all the Fs and flats on all the Bs. Free thinker that he was, Bartók preferred to write a key signature with a B-flat and an F-sharp. (Coltrane sometimes used that method too.)

Making up your own custom key signatures certainly makes writing in exotic scales easier. Unfortunately, it makes your charts harder to read for people who aren’t used to your system. Conventions can be annoying, but they exist for a reason.

Don’t stop here!

Continue learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Ryan Lott, and the acclaimed Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.