Welcome back to the dance floor, Quick Trackers! Once a month, we hook you up with a short production or songwriting challenge, aimed at helping to up your musicianship. To respond to the challenge, just email us, leave a comment, or post to social media with the hashtag #quicktracks and tag us @learntosoundfly.

…And we’re back! This week, we challenge you to produce a short groove (30-60 seconds) based on the dreamy Lydian mode. There are no constraints other than the fact that every note you use should belong to the Lydian. No non-Lydian notes allowed!

What do we mean by groove? It’s really kind of simple: any short piece of music that has a rhythm to it. If you’re a producer, slam out a fun little drum-and-bass loop. If you’re more of a composer, lay down an ostinato and plaster a melody on top.

And if you’re not sure what the Lydian is, we got you covered below — or you could sign up for our free course, Theory for Producers: The White Keys and Major Modes, to learn all about it (and so many other scale modes) in more depth.

The Magic of Modes

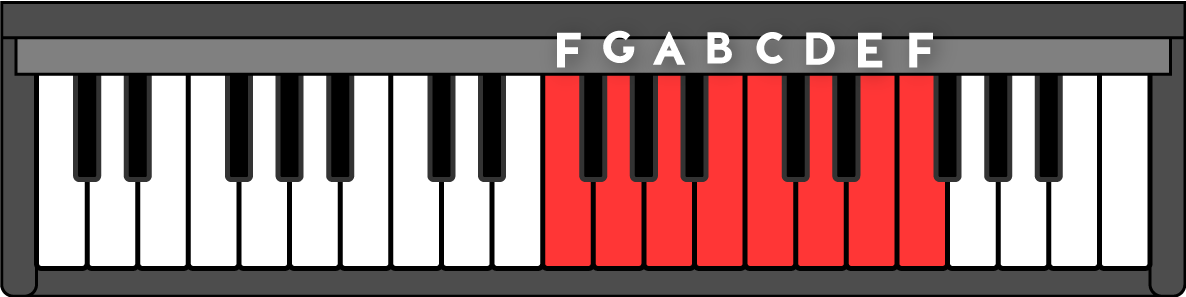

Picture the white keys of a piano or keyboard. They march unceasingly out from the center, interrupted by a hopscotch pattern of black keys. If you play them in a row, starting on C and ending on C, you’ll get that oh-so-famous musical motif: the C Major Scale.

But if you continue playing the white keys in a row starting on different keys each time, you’ll notice that the overall “sound” or tonality is different depending on which key you start on. Playing D to D or A to A gives you more of a sombre, minor sound, while playing B to B gives you a complex, evil-villain-ish tonality. And so on.

What you’re hearing in each case is the magic of modes. A mode is basically what we call the different tonalities you can get by playing the same notes but starting on different keys. There are seven different modes you can create by using only the white keys, each one starting on a different note, like A to A (Aeolian), or G to G (Mixolydian), or C to C (Ionian). Or, in the case of the Lydian Mode, F to F.

The Dreamy Scale

The Lydian is one of those crazy scales that has hardly any sharp edges. It takes one of the two “dissonances” in the major scale — the interval between the third and fourth notes — and arguably smooths it out by raising the fourth (although in doing so, it also adds a new tension between the fourth and fifth scale degree). Let’s take a look.

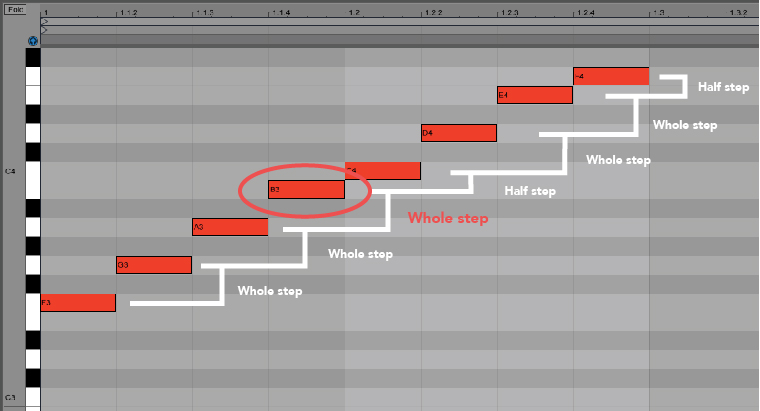

On the white keys, you can get the Lydian mode simply by playing all the white keys between F and F. Here it is in a DAW shown with MIDI. I’ve marked the key interval in red.

As you can see, the Lydian disrupts the normal pattern of the major scale by changing the interval between the third and fourth notes from a half step to a whole step. It’s actually pretty amazing how this subtle change can completely change the entire vibe of the scale.

Another thing you might notice is that the Lydian scale shares all the same notes as a major scale just starting on a different note. In order to make it really sound Lydian then, it’s all about emphasizing that different starting note. For example, when writing in Lydian using the white keys, the F note becomes home base, rather than C. Doing this in your writing will maximize the dreaminess of your sound.

The Lydian in Action

The Lydian is one of those scales that doesn’t show up a lot in pop music but appears in jazz frequently, and certain turn-of-the-century classical composers like Debussy and Ravel loved it. That said, it does pop up from time to time.

In our free course, we talk about Katy Perry’s use of the scale in her song “Teenage Dream.” Another example might be Radiohead’s “All I Need” or Björk’s “Aeroplane,” two songs that both really explore the raised fourth with their melodies.

What all of these songs share musically is that they float above the resolution, never allowing the listener to land back home where they expect. The melody just hangs. It’s a really beautiful feeling.

Personally, as a pianist, I live by the Lydian. If I’ve written a song in a major key, and I think it’s a little boring (because, you know, the major key), then I’ll just try raising the fourth to see what happens, and almost invariably, I like it better. It allows you to float along, to play with your audience’s expectations, and to explore a new tension between the fourth and fifth notes of the scale that you don’t normally have.

I personally find that it goes best with a healthy dose of major seventh and major ninth chords.

Are you ready??? Give it your best shot!

Still struggling with the major scale? Here’s a quick primer. Check it out!