+ Welcome to Soundfly! We help curious musicians meet their goals with creative online courses. Whatever you want to learn, whenever you need to learn it. Subscribe now to start learning on the ’Fly.

Trying to describe 2020 thus far in any concise form of writing leads me in one moment to a cascade of words of varying levels of comprehensibility, in the next moment to an utter loss for words.

Language is a strange thing; depending on the care, responsibility, and thoughtfulness with which it’s handled, it has the potential to be a super-power or a super-weapon. It points inward to our thoughts and outward to our actions — it’s both an inescapable reality and an invaluable ally in conceiving and sharing ideas. In our growth as people, I’m not sure it’s possible to overstate just how important and powerful of a tool language can be.

Despite about 10 years of experience as a teaching artist composing with young musicians, I still feel like a clumsy group speaker, particularly in the classroom, and I’m growing painfully aware of just how much I use words in my teaching. Like, way too many words. Sometimes these words seem useful and constructive, but more often than not they seem to be directives, or rambling one-sided projections of thoughts to a group of voices who deserve to be heard — not just talked at in silence (in online settings, people can literally be “muted,” which is creepily literal).

Having gotten into elementary school education through a weird combination of open-ended artistic experiments (“I’d like you to draw these nine measures of a Beethoven string quartet however you want.”) and oddly specific assignments (“I was hired to help you turn this fairy tale into a song in Cantonese in the next 45 minutes.”), I think I’ve often approached my time in the classroom with either a prepared personal inquiry to satisfy, or a series of objective task boxes to tick. I know, deep down, that this is not what teaching is about.

I know that those who join me in the classroom deserve so much more than this.

The more time I spend learning about a broad range of projects that involve creative professionals and young musicians working together (Nathalie Joachim’s work with the Kaufman Music Center, and Elizabeth A. Baker and Thanya Iyer’s projects with the Price Hill Creative Community Festival, and my time teaching at Little Opera come immediately to mind), and actively engaging with critical pedagogy (bell hooks, Paolo Freire), the more I am able to find language for ideas that, to me, point towards a more thoughtful way of working with young artists in the classroom.

The Classroom as a “We” Space

I noticed recently that a lot of my teaching is riddled with “you/me” dichotomies in both activities and language. I still see benefits to this structure in the context of play, but I have been amazed by the amount of creativity and resourcefulness that results in projects that are based on “we”-based challenges and inquiries as opposed to individual ones.

A deliberate effort to use language rooted in “we” has resulted in questions like:

- What do we notice about a particular thing we’ve made?

- What are some words to describe what we hear, or want to hear?

- How can we turn these 5 random sounds into a musical beat?

- How can we turn our bodies into the shape of a giant birthday cake in the next 10 seconds?

- What are our goals for today? For the next time we meet?

Every individual in a group has their own voice to be shared and means of making sense of the world — but I also wonder if, when done right, a “we”-based approach to learning can often amplify and encourage our personal senses of empowerment and resilience by applying them to a collective purpose.

+ Learn production, composition, songwriting, theory, arranging, mixing, and more — whenever you want and wherever you are. Subscribe for unlimited access!

Building a World from the Small Things That Are Given

Sometimes I think I get hung up on what we need to achieve as a group, when I could be focusing more on encouraging the ideas that we as a group already have. Instead of asking questions like: “what will the end result of this look like?” I wonder if a more beneficial approach is something like: “how will this seed of an idea grow if we nurture it?”

The resources at a group’s disposal — from meeting time, to internet connection speed, to the available artistic implements — are all initial conditions with the potential for building a creative world that can go as far as a group’s imagination is ready to take it.

One of the coolest projects I’ve seen materialize started with asking a group of 5th graders learning ukulele, “if you could design your own curriculum for this instrument, what would it look like?”

With no expectation about the end result, they invented original sounds (and musical notation to go with them) and organized those sounds into compositions that, over several weeks, evolved from simple patterns to unbelievably sophisticated constructions, like 5-foot-long musical canons taped in a circle and solo pieces with a custom-made music box duct-taped to the front of the instrument.

Instead of focusing on pre-fabricated achievement standards, the group devised goals based on their ideas and resources from week-to-week, and their ingenuity soared. I wonder what other creative situations could arise when an inquiry is rooted in growing what is given, not finding what is missing.

Spending More Time Listening Than Speaking, Asking Questions Than Offering Answers

This is hard for me, especially when I feel as though I am constantly calculating possible solutions to the obstacles a group is dealing with creatively in the classroom. But I’m finding that these instincts are often not honoring the richness and complexity of the creative process for my young collaborators as much as they are a kind of cheap, time-saving shortcut.

In fact, when I can put those instincts to suggest “quick fixes” aside and just listen to the ideas at play instead of asserting my own voice into the project — offering encouragement, observation, and legitimate questions of curiosity when appropriate – the trajectory of a project beams with pure, collaborative joy that is miles beyond my near-sighted visions and expectations.

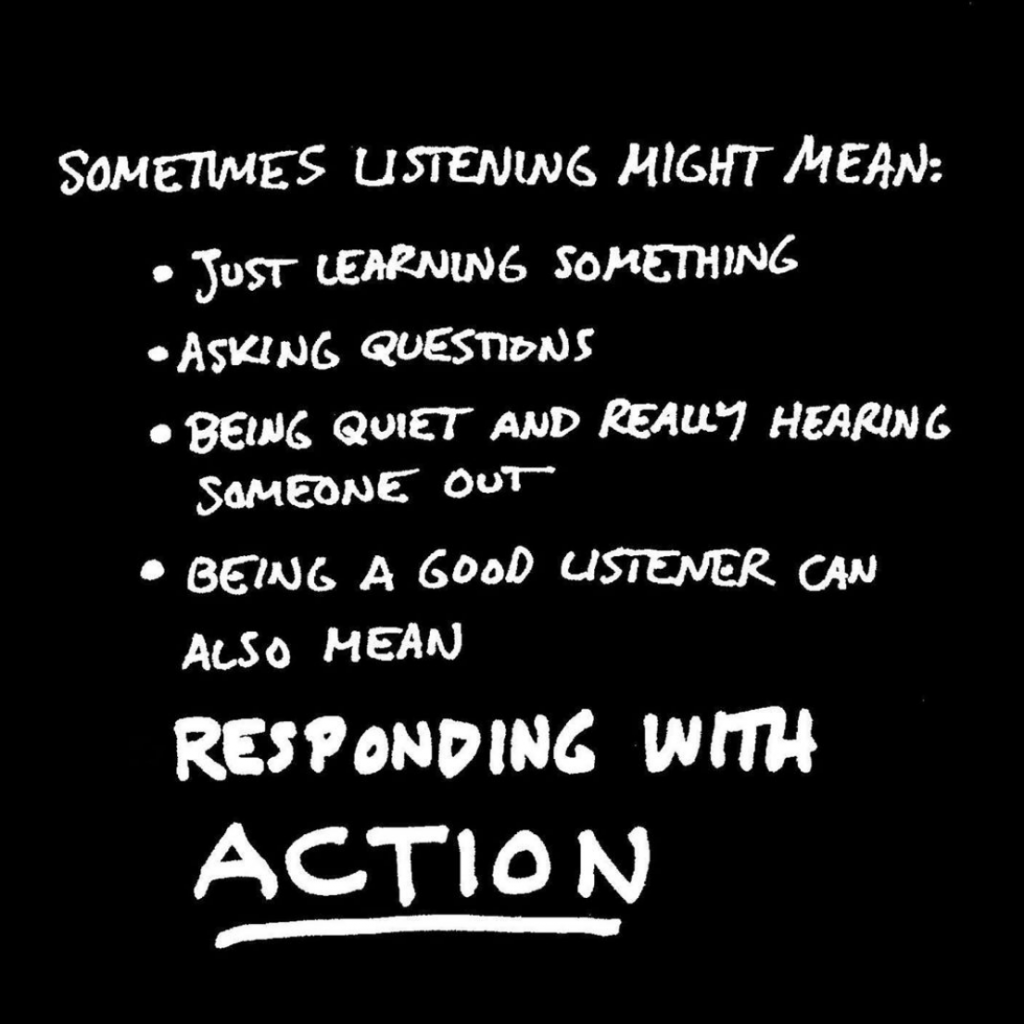

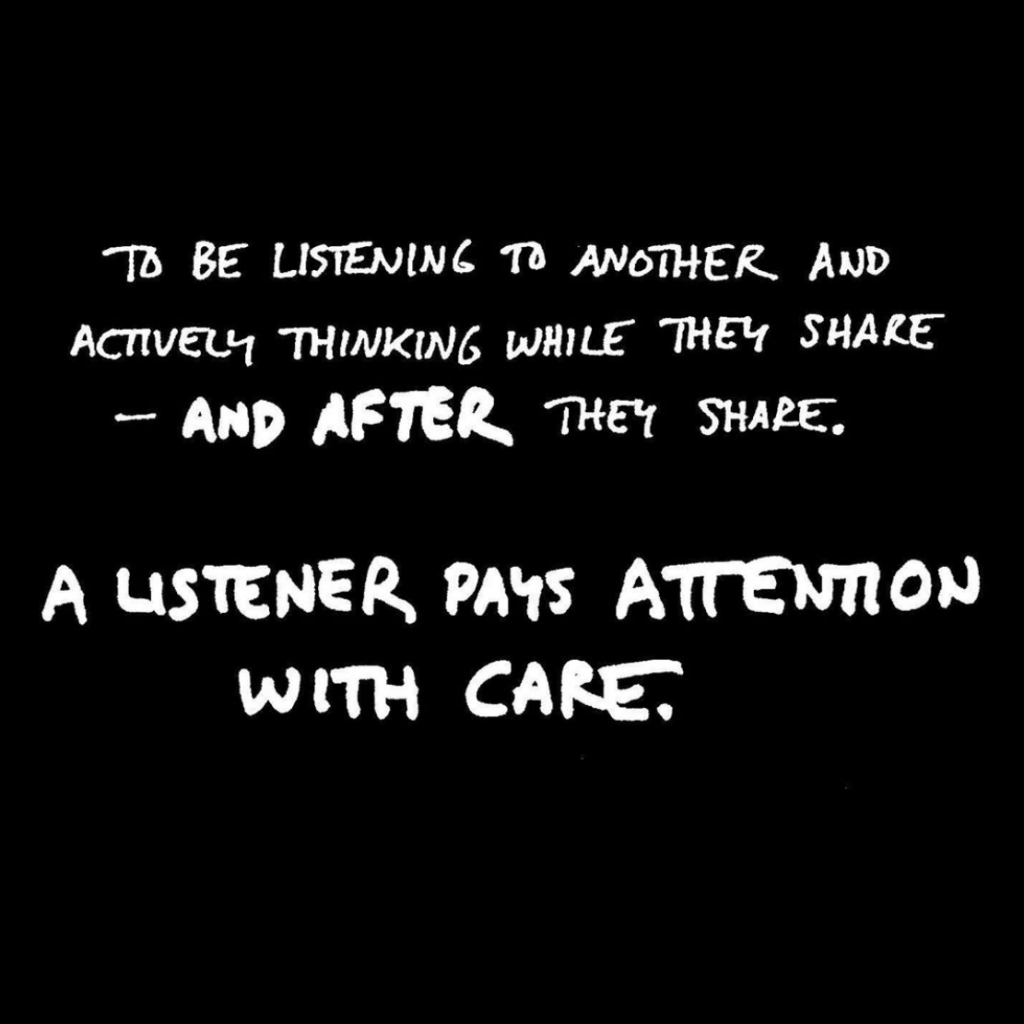

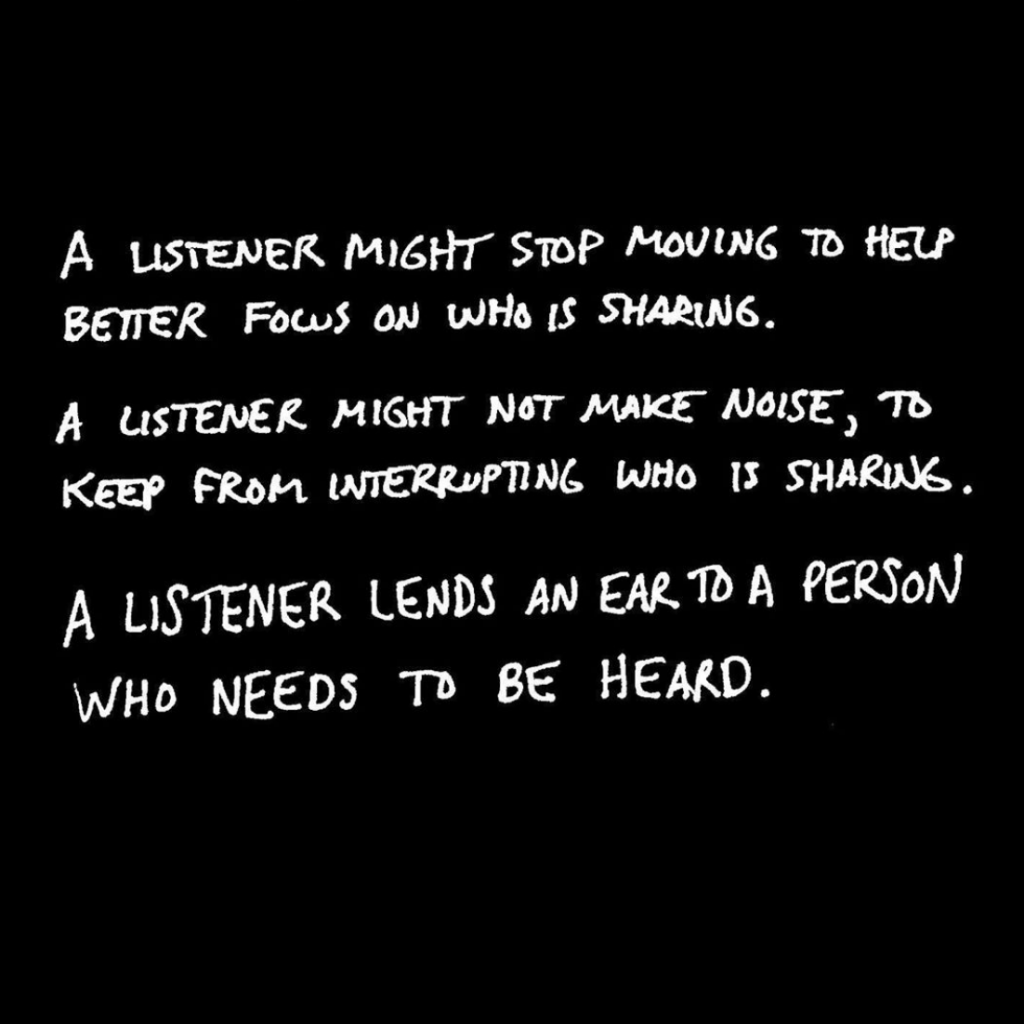

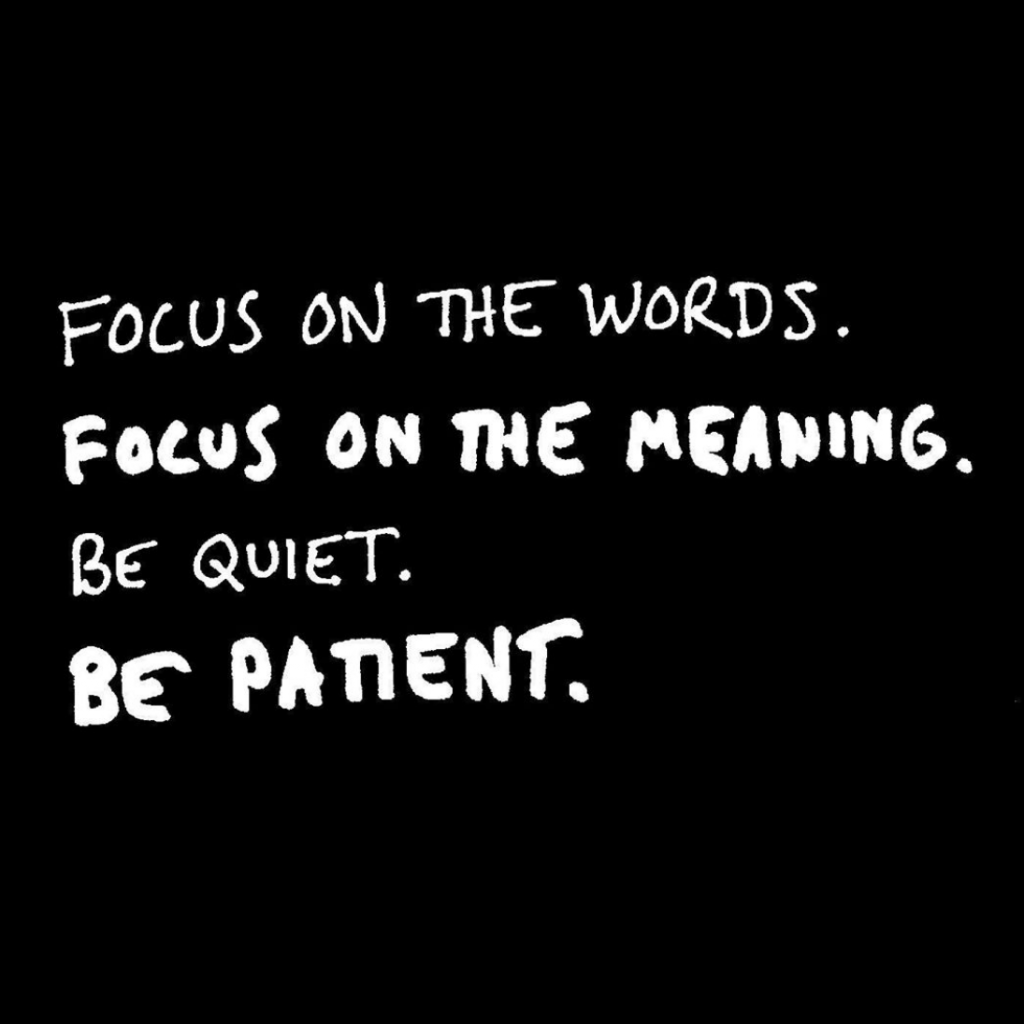

A few years ago, I asked a group of middle schoolers to share with me what the idea of “listening” meant to them. As is often the case, I think my students can sum up a lot of these ideas I’m struggling to express to you with far more clarity than I ever could.

I’m endlessly grateful for the opportunity to listen to the voices of young artists every day, to learn from them, and to grow.

—

Improve all aspects of your music with Soundfly.

Subscribe here to get unlimited access to Soundfly’s premium course content, an invitation to join our private Slack community forum, exclusive perks from partner brands, and massive discounts on personalized mentor sessions for guided learning. Learn what you want, whenever, with total freedom.

—

Danny Clay is a composer and teaching artist from Ohio, currently based in San Francisco. His work is deeply rooted in curiosity, collaboration, and the sheer joy of making things with people. His projects often incorporate musical games, open forms, found objects, archival media, toy instruments, classrooms of elementary schoolers, graphic notation, digital errata, cross-disciplinary research, and the everything-in-between.