Common idioms such as “seeing is believing” give our eyes the central role in our engagement with the world. But there is little doubt that listening plays a critical part in how we navigate and understand our environment.

Historically, our ears, not eyes, revealed what lay beyond the light of the campfire. And importantly, our ears helped us recognize what lay behind us, out of sight. Sound has the profound ability to haunt, shock, and terrify. It has a primordial quality that reaches deep inside us.

Recently, for instance, in preparation for Riverfire, an annual fireworks display in Brisbane, a pair of FA-18 Super Hornets throttled directly over my house. My two-year-old son was in the yard, and as I stepped outside to look at the planes, I saw him hurtling up our driveway, tears streaming down his cheeks.

He couldn’t see the planes as they passed overhead before their sound hit us. But their unnatural volume and the coarse noise of their engines triggered a palpable and overpowering sense of unease and distress. Sounds heard without a visible source are known as acousmatic.

To cope with them, we have created various narratives and myths. In Japanese mythology, the Yanari, a word that references the sound of a house in earthquakes, is said to be a spirit responsible for the groaning and creaking of the house at night. In Norse mythology, thunder was ascribed to the god Thor.

Given its profound emotional impact, it’s not surprising that sound has also been used as a device for exerting power and control. In recent years, the use of sound (and music) as a weapon has increased, as have our abilities to better exploit its potential.

From Long Range Acoustic Devices used to disperse protesting crowds to military drones that induce a wave of fear in those unlucky enough to be under them to songs blasted on rotation at Guantanamo Bay, we are entering an age where sound is repositioned as a tool of terror.

How Sound Affects Us

Sonic affect, in psychological terms, is created through aesthetic qualities: the timbre of the sound and how we receive it through our mesh of social and cultural understandings. The volume, duration, and actual material content of a sound all play a part in how it affects us.

Broadly speaking, most of us hear audible frequencies between 20Hz (very low sounds) and 20,000 Hz (very high sounds). However, in certain circumstances, sound that exists above and below our hearing range can also be experienced.

When considering the physiological impact of sound, the two critical aspects are frequency and volume. The sound we feel in our bodies is usually a low-frequency sound. And infrasound is of such low frequency it cannot be heard with human ears. Yet it still causes an unconscious physiological anxiety.

It’s this dual recognition, of the ears and the body, the psychological and the physiological, that’s vital to the use of sound as a weapon.

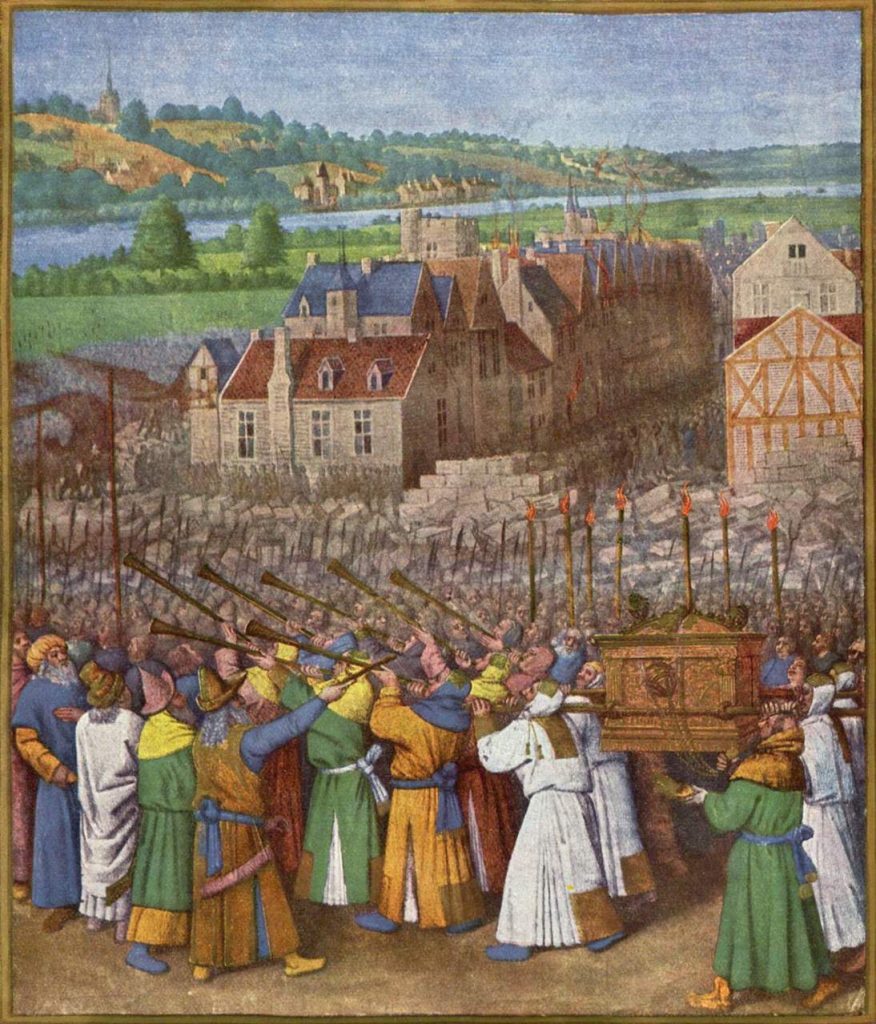

The Battle of Jericho, described in the Bible, is an apt place to begin an examination of how sound came to be utilized as a weapon. Loosely, the story goes that Joshua’s Israelite army was able to break down the walls of Jericho using trumpets. Though there is no historical basis for this story, it recognizes the physiological and the psychological implications of sound in warfare.

Sound can be used at high volume to create powerful effects on objects. It’s unlikely, of course, that brass instruments could crush a city’s walls without serious mechanical and engineering assistance. But the shock wave from a trombone is nothing short of a micro-sized explosion.

The Battle of Jericho also reminds us how sound can fatigue us. Like noise pollution today, sonic fatigue leads to a psychological debilitation. Perhaps the Israelite army was able to wear its enemy down through prolonged high volume sound projection, inducing sleep deprivation, and fatigue-induced panic.

Moreover, the constant blasting of the horns would act as a constant reminder that at any point, the armies might attack. The audible threat in and of itself becomes a device of terror.

One of the most frightening recently discovered weapons of sound is the Aztec Death Whistle, a pottery vessel often shaped like a skull, that was used by Mexico’s pre-Columbian tribes.

Blowing into it makes a sound that has been described as “1,000 corpses screaming.” Used en masse, an army marching with death whistles would surely have been terrifying.

20th Century Terror

One of the most iconic representations of sound as a means of creating fear was developed during the Second World War. Germany’s Stuka Ju-87, a dive-bomber fitted with a 70 cm siren dubbed the “Jericho Trumpet,” was a sophisticated terror device.

Its success influenced the V1 Flying Bomb, known as the Buzzbomb due to the acoustic design of its engine. While its blast capacity was modest, its power as a sonic threat demonstrated the growing recognition of psychological terror as a destructive tool of war.

Following World War II, the development of supersonic flight heralded unprecedented exploration of aerial sonic phenomena, including the sonic boom. A sonic boom is the sound made when a plane exceeds the speed of sound, 768mph in dry air at 68°F.

During 1964, Oklahoma City became a US government testing ground for sonic booms. A wealth of information was produced, including an assessment of its rather pointed psychological impact on the city’s citizens. Two decades on, the US government was using sonic booms against Nicaragua as part of a campaign to destabilize the Sandinista government of the day.

During the Vietnam conflict, meanwhile, US troops played a soundtrack known as Ghost Tape Number 10 against the soldiers of the National Liberation Front. As part of Operation Wandering Soul, American forces played an unsettling tape collage that tapped into Vietnamese beliefs that ancestors not buried in their homeland roam without rest in the afterlife. This spooky mix of voice, sound, and music was intended to haunt Vietnamese soldiers and encourage them to abandon their cause.

The Sound of Fear in the 21st Century

In the past decade, the increased military use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, colloquially known as drones, has led to new forms of sonic terror. The word drone refers to both a worker bee and the sound it makes. Like the bee, drones have distinct sonic characters depending on their design.

These sonic characteristics have been shown to produce, for those living under them, degrees of annoyance, anxiety, and fear. Civilian descriptions of drone activities in the report Living Under Drones, prepared by a team at Stanford University, document what some interviewees describe as a “wave of terror” upon hearing them. Their sound, both up close and at a distance, is particular and pervasive. En masse the reference to bees is obvious.

A recent military exercise undertaken by Israel against Palestine in 2012, titled Operation Pillar of Defense, extensively used the sonic capacity of drones. During this operation, sound was used as a constant reminder that at any stage strikes could be made. This auditory threat — added to the general discomfort of constant buzzing and whirring of machinery overhead — proved a powerful weapon.

On the ground, too, sonic weapons such as the Long Range Acoustic Device are being increasingly deployed. Originally created as a means of long distance communication in marine settings (over distances as far as three kilometers), the device has been widely used since the early 2000s.

[Turn your volume way down before watching the following video!]

During Pittsburgh’s G20 protests in September 2009, it was deployed to disperse crowds with incredibly high volume, directional sound. Use of the device led to subsequent legal action against the city of Pittsburgh with one claimant, Karen Piper, receiving damages of $72,000 after suffering permanent hearing damage.

Almost all states in Australia have acquired these acoustic devices in recent years, though their usage is primarily for communication during siege and disaster situations, not crowd control. Still, the law and enforcement implications of these devices and the emergent field of acoustic jurisprudence are sure to become of greater interest.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Loud Silence and Quiet Sound: The Illuminating Music of Toru Takemitsu”

The Terror Jukebox

Recorded music, too, is an increasingly powerful weapon used to “break” prisoners during interrogation. The formula for music as a form of terror is equal parts volume, aesthetics, and repetition. It’s a methodology that recognizes we have no earlids. Unlike our eyes, we cannot shut out sound, and this means we’re vulnerable to it in ways we don’t always consider.

In the early 20th century, Luigi Russolo’s Intonarumori — a group of experimental acoustic instruments — heralded an assault on the harmonic canon of music. The performances he gave with these instruments created outrage and discomfort in his audiences. In his manifesto, The Art of Noise, he espoused a violent rethinking of the potentials of music and noise.

In Greece between 1967 and 1974, the Military Police and the aptly called Special Interrogation Unit used music in two distinct ways. It was played very loudly over long periods of time to detainees. And prisoners were pressured to undertake periods of forced singing with renditions of the same song over and over again.

Similarly in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, a so-called Music Room was used to break hooded detainees placed in internment. Extremely loud white noise was blasted at them. Outside the Music Room, a device called The Curdler was also used to torture prisoners — it emitted a loud sound at a frequency range specifically sensitive to humans.

In 1989, meanwhile, the US government launched Operation Nifty Package. Its aim was the extraction of the opera-loving Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, who had sought asylum in the papal nunciature of Panama City. After a lengthy playlist of loud rock and heavy metal — including Styx and Black Sabbath — was blasted at the building in which he sheltered, Noriega was ejected from the diplomatic quarter.

One of the most extraordinary sonic duels occurred in 1993, when the Branch Davidians and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives officers faced off during the infamous siege of Waco. The government agencies assaulted the Davidian compound with repeated plays of Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walkin’,” droning Tibetan mantras, recordings of rabbits being slaughtered, and Christmas carols. In turn, the Davidian leader David Koresh retaliated with broadcasts of his own songs — until the compound’s power was switched off.

Still, this encounter was primitive when compared to contemporary methods of music torture. The sound systems used during Waco, for example, were largely directionless and agents working for the government needed earplugs to block the effects of their own soundtrack.

Over the last 10 years, the use of music as torture has been cemented in facilities such as Guantanamo Bay and other undisclosed detention camps. A branch of the United States Military, Psychological Operations, is renowned for its ability to influence behavior and assist in the psychological “breaking” of detainees through the use of sound.

The choice of music used as part of these interrogations at Guantanamo was wildly disparate. Death metal band Deicide’s infamous song “Fuck Your God” was often used, as well as aggressive hip-hop.

But so, too, were the songs of Britney Spears (“…Baby One More Time” was played often) and, perhaps most surprisingly, “I Love You” from Barney & Friends.

The writer of the Barney & Friends song, Bob Singleton, was shocked at its use. How, he wondered, could a song “designed to make little children feel safe and loved” drive adults to an emotional breaking point?

His disgust at the use of his music in this context wasn’t uncommon. Indeed, artists such as Massive Attack, Nine Inch Nails, Rage Against the Machine, and others teamed up with the NGO Reprieve to create the Zero dB coalition against the use of music-related torture. Tom Morello, then guitarist with Rage Against the Machine, spoke of inmates being blasted with music for 72 hours “at volumes just below that to shatter the eardrums.”

The Canadian electro-industrial band Skinny Puppy took things one step further. In 2014, it invoiced the US Defense Department $666,000 for the unauthorized use of its music at Guantánamo Bay.

There’s little doubt music will continue to play a role in the struggles around terror. The potential of sound as a weapon is, sadly, still in its infancy. Sonic weapons, after all, leave no physical marks. Thus, they are perfect for those who wish to remain untraceable.

*Lawrence English’s newest album Cruel Optimism is out now on LP/CD/digital via Room40. Order the record here.

—

Lawrence English is a composer, media artist and curator based in Australia. Working across an eclectic array of aesthetic investigations, English’s work prompts questions of field, perception and memory. He investigates the politics of perception, through live performance and installation, to create works that ponder subtle transformations of space and ask audiences to become aware of that which exists at the edge of perception. He is the director of the record label Room40.

Lawrence English is a composer, media artist and curator based in Australia. Working across an eclectic array of aesthetic investigations, English’s work prompts questions of field, perception and memory. He investigates the politics of perception, through live performance and installation, to create works that ponder subtle transformations of space and ask audiences to become aware of that which exists at the edge of perception. He is the director of the record label Room40.