+ Learn to craft more compelling beats and warped, broken rhythms with Son Lux’s Ian Chang. His innovative course is out now on Soundfly.

My parents would sometimes take me on drives in the countryside, with the intention of getting lost and finding their way back home. It always worked out fine with my dad at the wheel, but it seems that I did not inherit his good sense of direction. Because given a choice, I will tend to take the exit or fork in the road that takes me further away from home.

So, I was that early-adopter nerd who printed out MapQuest maps in both directions anytime I had a driving trip planned. And who to this day pops out of the subway in NYC looking slightly frazzled until I can figure out which direction is which.

Being lost is no fun, but the upside of getting lost a lot, is that you discover a lot of new things and places that you otherwise wouldn’t have.

As it turns out, a similar phenomenon occurs in teaching and learning. And research suggests that we may be hindering our students’ learning by trying to be too helpful. Wait, how’s that now?

The Traditional Model

Generally, teaching looks something like:

- Explain how to do something (lecture)

- Show students what it looks like in action (demonstration)

- Fix their off-target attempts, to help them minimize “failure,” and reward them for their successes (feedback)

This sequence tends to emphasize getting to the correct answer as expeditiously as possible. It’s how schools are often set up. It’s how many of us were taught. (And it’s how we parent as well.)

The “tell-show-do” model makes a lot of sense — but there’s little room or time for exploration, floundering around in the dark, and discovery. And growing evidence suggests that the experience of being lost may actually enhance learning in the long run. Even though at first, it all looks like a hot mess.

But how could that be? Isn’t the goal of learning to minimize mistakes and failure?

“Productive Failure”

A pair of researchers (Kapur & Bielaczyc, 2011) conducted a study of “productive failure” to see if early floundering would lead to better learning than the traditional teaching approach (“direct instruction”). They took two 7th grade classrooms, and gave them a 30-minute, 9-question pretest to see how much they already knew about how to calculate average speed.

And then their learning experience began to diverge.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “Words Matter: How to Ask and Give Advice With Respect.”

Direct Instruction Group

The direct instruction class began learning about average speed with a lecture. The teacher explained the concepts, worked through some examples, encouraged questions, and had students solve practice problems.

Then they reviewed the problems and discussed the solutions. For homework, they were assigned similar problems in their workbook. The problems ranged from simple to moderate in difficulty, but were essentially plug-and-chug-type questions. Here’s an example:

Jack walks at an average speed of 4 km/hr for one hour. He then cycles 6 km at 12 km/hr. Find his average speed for the whole journey.

They repeated this lecture-practice/homework-feedback process for 7 class periods. Pretty typical-sounding process, right?

Productive Failure Group

The productive failure class was split up into small groups, and each was tasked with solving two complex problems like below:

Hummingbirds are small birds that are known for their ability to hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their wings. Each year they migrate approximately 9000 km from Canada to Chile and then back again. The Giant Hummingbird is the largest member of the hummingbird family, weighing 18-20 gm. It measures 23cm long and it flaps its wings between 70-80 times per minute. For every 18 hours of flying it requires 6 hours of rest.

The Broad Tailed Hummingbird flaps its wings 100-125 times per minute. It is approximately 10- 11 cm long and weighs approximately 3-4 gm. For every 12 hours of flying it requires 12 hours of rest.

If both birds can travel 1 km for every 550 wing flaps and they leave Canada at approximately the same time, which hummingbird will get to Chile first?

They were given these problems with no teacher support or guidance, but simply allowed two class periods to try to solve each problem (4 classes total). There was also no homework, though they did receive extra problems to work on individually when the group problems were complete (2 class periods).

After 6 sessions of working on their own, the class spent their final class session sharing their solutions and strategies with the teacher and each other. Only then did the teacher finally explain how to solve these problems the “correct” way, and help the students go through their previous work, fix their mistakes, and ensure they could arrive at the correct answer.

Ultimately, the productive failure group spent 7 class sessions working on calculating average speed, just like the direct instruction group. But they spent most of these classes floundering on their own, and doing many things wrong. It was only during the 7th and final class that they learned the correct way to approach these problems.

So did all this floundering help, or hinder their learning?

+ Learn production, composition, songwriting, theory, arranging, mixing, and more; whenever you want and wherever you are. Subscribe for full access!

Then, the Post-Test

To find out, both classes were given a 35-minute, 5-item post-test. Which consisted of:

- three simple problems (like the ones the direct instruction group worked on)

- one complex problem (like the one the productive failure group had to do)

- and one type of problem that neither of them had done (basically, answer the question and pick which graphic best represents the answer)

Early Stages of Learning

As you can probably imagine, the direct instruction group did waaaay better than the productive failure group in the early stages of learning. The direct instruction group averaged a score of 91.4% on their homework.

Meanwhile, the productive failure group performed miserably on their unguided attempts to solve the complex problems. Only 2 out of the 12 groups (16%) arrived at the correct solutions. And when they had to work on the problems individually, their average score of 11.5% was even worse.

But a very different picture emerges when you look at the groups’ performance on the post-test.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “A Musician’s Guide to Listening With Empathy.”

Later Stages of Learning

On the final test, the performance between the two groups flipped, and the productive failure group outscored the direct instruction group by a significant margin.

On the simple problems, the productive failure group earned an average score of 84.8% (vs. 75.3% for the direct instruction group). And on the complex problem, the productive failure group earned an average score of 59.7% (vs. 42.4% for the direct instruction group).

But isn’t failure and floundering and mistake-making bad? Why the heck did this work?

Short Term Performance vs. Long Term Learning

Students often ask for help before trying to solve problems on their own. And teachers are accustomed to providing help.

I mean, it’s certainly faster and more efficient in the short term to offer the right fix, technique, etc., rather than withholding the right answer or strategy and letting the student struggle, search, and look in all the “wrong” places.

However, in much the way that spaced, random, and variable practice lead to worse performance in the short term, but better performance in the long term, it seems that the goal of productive failure is not to get the correct answer faster and more easily via shallower learning (“unproductive success”), but instead, to cultivate a deeper understanding of the fundamental principles and various ways of arriving at a solution even at the expense of short-term performance.

Ownership and Engagement

The productive failure approach also seems to increase engagement in the learning process. Here are some quotes from teachers who were involved in the study:

“I was not only surprised by the kinds of ideas and methods students developed to solve the problems but also their ownership of their ideas…I mean, during the consolidation, I could see that they really wanted to know why their methods did not work, or how someone else’s method was better, and how the “correct” way of solving the problem was better…”

“…in our usual lessons, they simply accept what we tell them, our explanations and stuff, this is how to do it and they just take it…but here, they were not ready to just take our explanations so easily, they wanted to defend their ideas and not give up without a fight sort of…I mean, not a fight but you know there was this engagement in understanding why, why, why…”

Take Action

How might you apply this concept to your teaching? Or even your own learning, for that matter?

One example that comes to mind is fingerings and bowings. I remember one of my early formative teachers withholding fingering recommendations when I was still quite young, encouraging me to come up with some on my own.

I felt totally lost at the time, and the idea of having to pull fingerings out of thin air was completely foreign. I thought I was supposed to do whatever was printed in the music, or whatever she gave me. I felt lost for a while, and I came up with some pretty funky fingerings, but over the years, I came to take great pride in thinking up my own clever fingerings and bowings designed to enhance the character of a phrase, or make challenging passages easier and more reliable under pressure.

Play Your Heart Out!

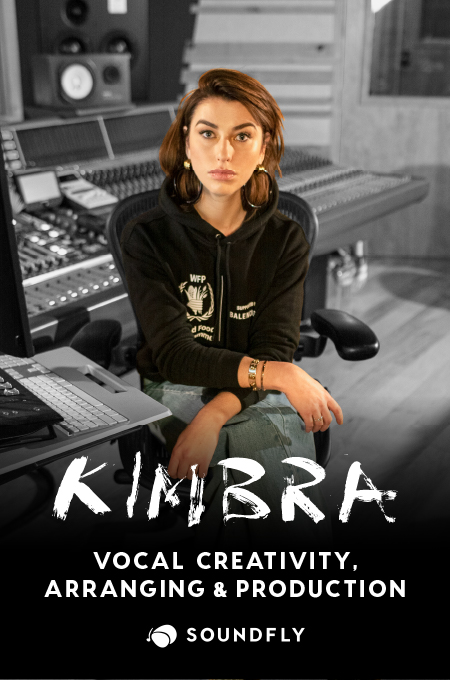

Continue your learning adventure on Soundfly with modern, creative courses on songwriting, mixing, production, composing, synths, beats, and more by artists like Kiefer, Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Ryan Lott, RJD2, and our newly launched Elijah Fox: Impressionist Piano & Production.

—

Performance psychologist and Juilliard alumnus & faculty member Noa Kageyama teaches musicians how to beat performance anxiety and play their best under pressure through live classes, coachings, and an online home-study course. Based in NYC, he is married to a terrific pianist, has two hilarious kids, and is a wee bit obsessed with technology and all things Apple.