I’m going to try and simplify this article as much as I can.

Partly due to the fact that I’m not a physicist and partly for the reader’s sanity.

Firstly, let’s talk about acoustic treatment types in general.

+ Enjoy access to Soundfly’s suite of artist-led music learning content for only $12/month or $96/year with our new lower price membership. Join today!

Types of Acoustic Treatment

Absorption

There are several different types of acoustic treatment that all have their own areas (or frequencies) in which they flourish. Absorbers, or absorption, do just that. Usually soft and spongy, these acoustic gems are the most popular type of acoustic treatment.

You’ve probably seen Auralex pyramids, wedges, or something similar lining studio walls or sporadically positioned in random spots around a room. Sound energy (vibration) hits the material and the thousands of tiny air pockets that make up the material remove the energy.

Have you ever screamed into a pillow? Well, I do constantly, and if you do, you’ll notice that it sounds very muffled. This is due to the acoustic qualities removed by absorptive materials. Absorption is great at removing higher frequencies. It will take some of the low end out, but because the physical sound waves are larger in the lower end, they tend to pass right through.

Bass Trapping

Another example is hearing a nightclub from the outside. The soft furnishings inside the building remove most of the higher frequencies, but the low beat of the music still travels through the walls. So, how do you get rid of the low end?

This is the hardest frequency range to deal with. The wavelengths of low frequencies are so large, and the energy they produce is greater. According to Wikipedia:

For sound waves in air, the speed of sound is 343 m/s (at room temperature and atmospheric pressure). The wavelengths of sound frequencies audible to the human ear (20 Hz–20 kHz) are thus between approximately 17m and 17mm, respectively.

This means that most of the low-end audio coming out of the speakers in the studio has a wavelength that’s longer than most rooms. This typically creates a buildup of low energy at the corners and walls of the rooms called standing waves.

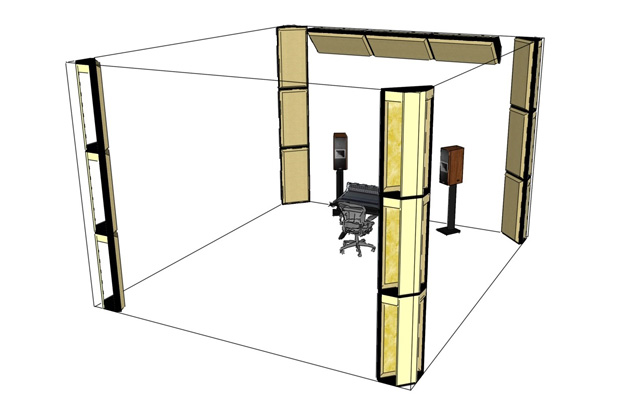

The treatment used to deal with these frequencies is bass traps. They normally consist of pieces placed in the corners of the room. The idea is for the bass frequencies to pass through them and get trapped in the corner pieces before they come back into the room.

Diffusing

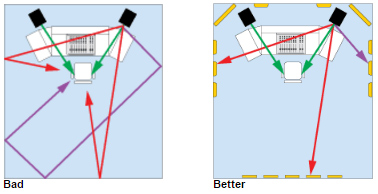

This brings me to the last major variation of acoustic treatment: diffusers. Sound acts like light in a lot of ways. If you shine a flashlight at a mirror, the light beam gets reflected back at the angle of incidence (i.e., if you pointed the light at the mirror at a 45-degree angle, it would reflect off the surface at 45 degrees and back into the room). Sound the same way.

Acoustic treatment is the act of stopping the sound bouncing off the various surfaces of the room. A diffuser jumbles up these reflections so they don’t return back into the room directly.

Reflection points are places in a mix room where the audio from the speakers hits the nearest walls and ceiling. The first reflections are known as early reflections, and it’s in the engineer’s best interest to kill these reflections. The reason being that if the engineer hears the direct sound vibration from the speaker to his or her ear, he or she will then get a second version of the same vibration that’s reflected off the nearest walls and ceiling but at a slight delay.

This confuses the brain and ultimately messes up the stereo image, which results in inaccurate mixes that could sound strange on different systems such as consumer headphones. These reflections happen behind the engineer, too, and reflect off the back wall thus reflecting back into the engineer’s ears with an even longer delay.

The best way to deal with this is to place absorption and/or diffusers at the reflection (or mirror) points. In my studio, I used absorptive sounds panels at the reflection points by the mix position and an acoustic curtain behind the mix position to deal with this. I wanted to be even more cautious with my reflection points and treat a larger frequency range, though, so I added a diffuser behind me.

What Frequencies Do I Diffuse?

Within the “diffusion” acoustic-treatment bracket, there are several types of diffusers that treat specific frequencies. I wanted something broadband, meaning it would diffuse as many frequencies as possible for my money.

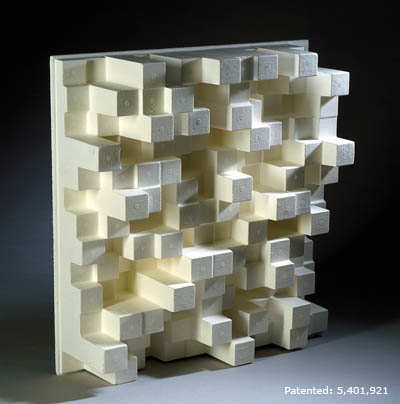

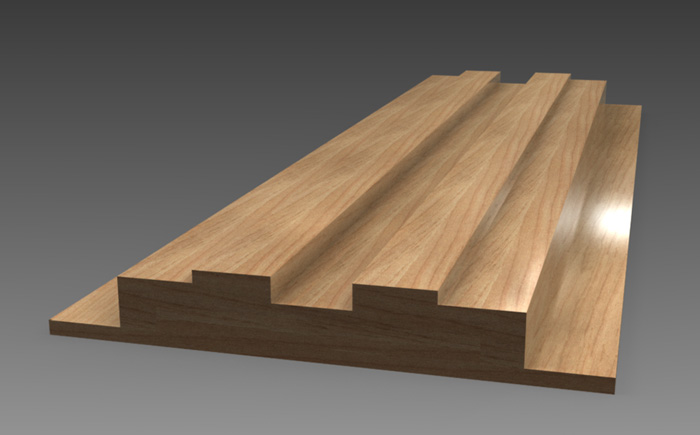

The studio at which I used to mix in London had an RPG Diffractal (fractal QRD diffuser), which offers the best of everything. It has deep gutters to break up lower frequencies and, within each gutter, even smaller gutters to break up the mid and higher frequencies. Each gutter varies at very specific depths — this is the part acoustic scientists have mathematically configured for optimum diffusion. As much as I wanted to add these not only practical but awesome-looking panels in my room, they’re bloody expensive!

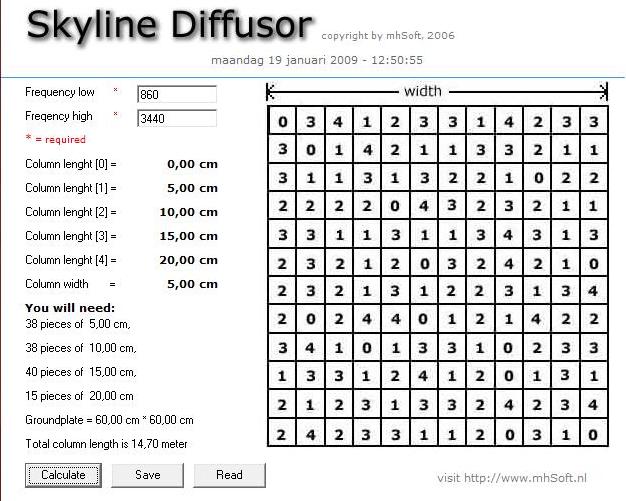

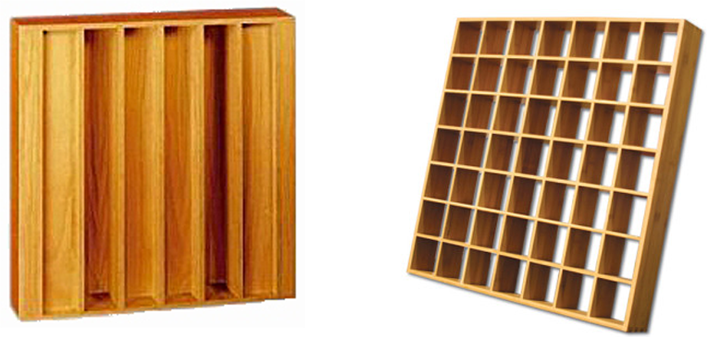

So, I did some research on how to build my own. The easiest diffuser to build seems to be the skyline diffuser. Lots of different-length squares positioned specifically on a set grid ably diffuse mid frequencies. Diffusers are extremely heavy, however, due to the amount of wood used.

The QRD diffusers are probably the next easiest to make but only cover lower-mid frequencies.

Building the Diffuser

I then discovered a panel designed by Tim Perry, and he very nicely offers the blueprints for free via his website. Download them here.

What I like about these diffusers is the range of frequencies that they attend to. They look really cool, and the carpentry is relatively straightforward – compared to building an RPG Diffractual diffuser at least!

He gives specific dimensions, which I actually didn’t stick to because I wanted to optimize my wood purchasing with a specifically sized panel. As long as you keep the ratios the same, the acoustic properties still work. If 300mm becomes nine inches for example, 100mm would become three inches (a third of the length).

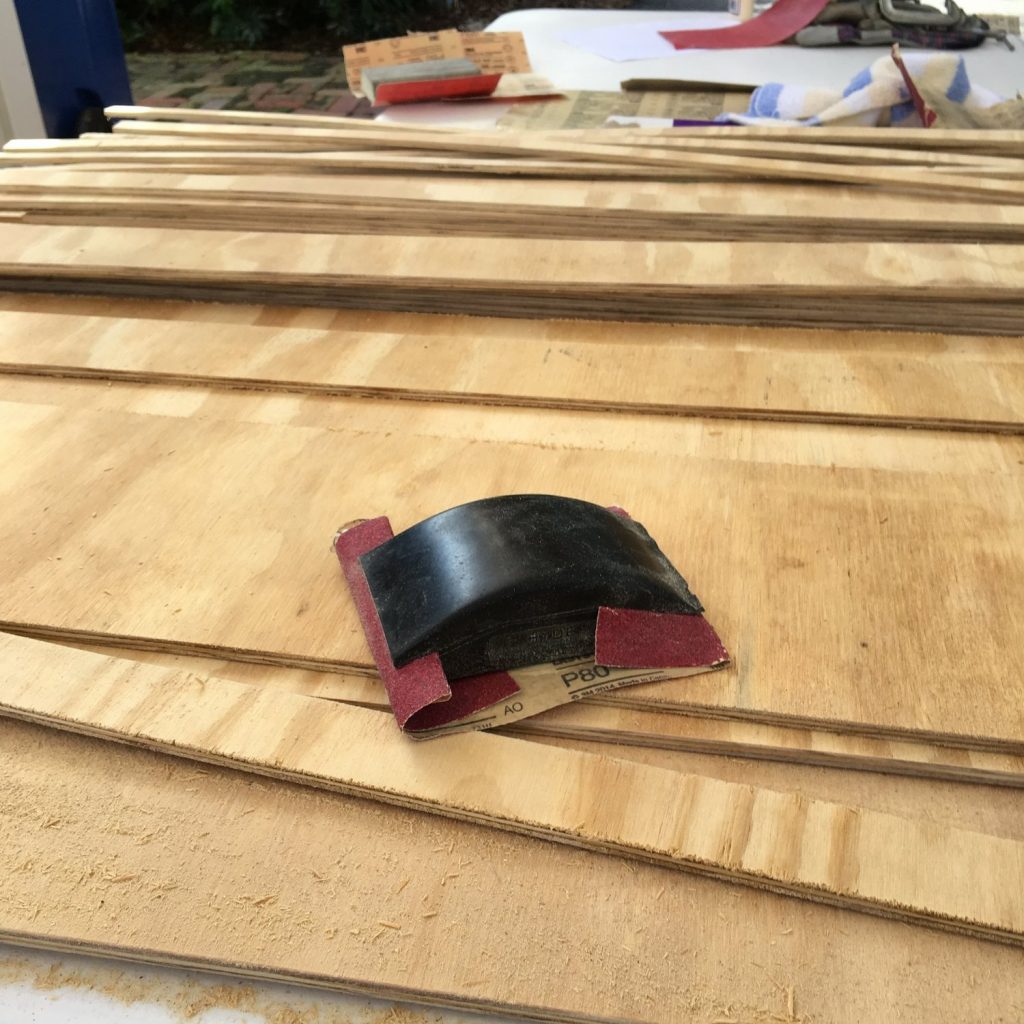

The next dilemma I went through was which wood to use. This is an aesthetic decision as well as a practical one. I wanted something solid but also not too heavy. I ended up buying 8’x4’x¼” thick plywood. I used the four-foot width of the plywood panel as the height of my diffuser and divided the eight-foot length into the calculated strips I needed. In retrospect, I should’ve used slightly thicker plywood, since it warped a little after the panel was complete. I rectified this by reinforcing wood on the back, but it would have been easier with at least 1/2” plywood.

With my measurements calculated, I penciled each strip that needed to be cut and, as precisely as I could, ran the circular saw down each line. Once each strip was cut, I sanded them all and started constructing the diffuser. This was just a case of layering and working out which strip goes where.

After the construction, I re-sanded the entire thing to get it ready for staining. I still had remaining stain from the audio workstation, so I just used that to keep the color scheme consistent with the rest of my studio.

Because of the layout of my studio, I decided to mount the diffuser on a barn door sliding rail with cables, dropping the height of the diffuser to be in line with my speakers. Not only does this look really cool and fit with the décor of my studio, but it’s also practical for sliding to one side so I can enter and exit the studio conveniently.

Having the diffuser in place has noticeably tightened up the stereo image from the mix position, as well as reduced some of the flutter echo originally present in the room.

Improve your music with creativity & curiosity on Soundfly.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel for weekly videos, or join Soundfly’s all-access membership to all of our artist-led online music courses, an invite to join our Discord community forum, exclusive discount perks from partner brands, access to artist Q&As and workshops, and more.

—