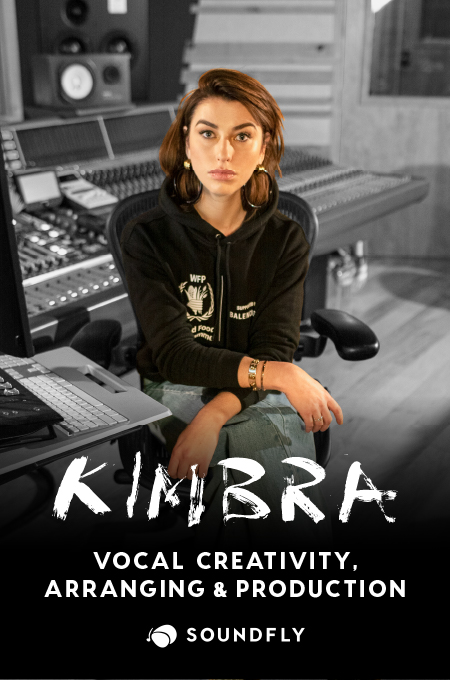

+ Learn from Grammy-winning pop artist Kimbra how to harness the full creative potential of your voice in song. Check out her course.

There’s a quote attributed to the violinist Jascha Heifetz in which he says that we should always be happy when performing. After all, if things are going well, we should be happy that things are going well. And if things are going badly, each note we play gets us closer to the end, so we should be happy about that too.

Still, it’s no fun to be stuck on stage when we’re having one of those bad days. Cringing at each botched shift and cracked note. Which just leads to a downward spiral of negativity and increasingly uninspired playing, as a part of us starts to seriously entertain the idea of stopping and walking off stage…

Of course, a week or month (or decade) later, when curiosity gets the better of us and we screw up the courage to listen to a recording of the performance, it’s often pleasantly surprising how decent we sound. How we can’t even find the horrible things that we were initially mortified by, and how many nice moments there are that we didn’t even remember.

So what’s the deal? Is it possible that we really do sound better on stage than we think?

Dress Rehearsals vs. Concert Performances

To learn more about how we perceive the quality of our performances, an interdisciplinary group of researchers ran a study involving 21 undergraduate and graduate-level piano students (Masaki et al., 2011).

Each student was videotaped doing a complete run-through of their repertoire in two different situations — a dress rehearsal and a performance (not something contrived specifically for the study, but a real honest-to-goodness performance they would have had to give anyway).

+ Read more on Flypaper: “The Zeigarnik Effect — and What the Heck It Has to Do With Music.”

Two Evaluations

Following their concert performances, the students completed an evaluation form designed to help them compare the quality of their concert performance to the quality of their dress rehearsal run-throughs. Ranging from memory to tempo to sound quality and expressiveness, they evaluated the degree to which their performance was worse, better, or the same as their dress rehearsal in eight areas (on a 7–point scale where 3=much worse; 0=same; 3=much better).

But the researchers carefully manipulated the timing of their self-evaluations. Each student completed one evaluation immediately after their performance — and then a second one, some time later while watching the recording of their performance — to compare their perception and memory of their performance vs. the reality of how well they played given an actual recording of the performance.

Meanwhile, a professional pianist completed the same comparative evaluation of the students’ rehearsal and concert performances, while reviewing video of the concert performances.

Then, the students’ ratings and professional’s ratings were compared to gauge the accuracy of the students’ self-ratings.

Student Self-Ratings vs. Expert Ratings

You can probably guess what happened.

The highest correlation was between the professional pianist’s evaluation and the students’ evaluations that they did while reviewing the video (.94). The lowest correlation was between the professional’s evaluations and the students’ evaluations that were completed based on their memory of the performance before they had a chance to watch their performance video (.79).

So all in all, the data suggests that the performers were able to evaluate the quality of their performances more accurately when they did so based on a video of their performance. When relying on only their memory of the performance, their evaluations were less accurate.

Why the difference?

Well, the major difference between dress rehearsal and concert performances, of course, is the amount of anxiety we experience. Might it be that our nerves make a difference in how we perceive the quality of our playing?

+ Learn production, composition, songwriting, theory, arranging, mixing, and more; whenever you want and wherever you are. Subscribe for full access!

Impromptu Speeches

A group of Canadian researchers (Ashbaugh et al., 2005) conducted a study of college students to see what role anxiety might play in the accuracy of our self-perceptions.

They took a class of 333 students and gave them an anxiety assessment to identify those who experience the most and least anxiety in social situations. The high and low socially anxious students were then asked to give an impromptu speech in front of an observer and video camera, told that the recording would be shown to other students at a later time.

Essentially the social phobic’s worst nightmare — like that dream where you get to the concert hall for a first rehearsal and discover that you prepared the wrong concerto.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “6 Tips for Optimizing Your Vocal Health.”

High Social Anxiety vs. Low Social Anxiety

Both the high-anxious and low-anxious groups completed self-evaluations of their speech in several areas. The interesting ones were related to performance quality and “presenter impression” (i.e. how they thought they came across to others).

As predicted, the high-anxious folks had lower self-ratings than the low-anxious folks. Ok, but that doesn’t necessarily mean anything because maybe their nerves really did cause their performances to suffer, right?

To check this out, two independent observers watched and rated both groups’ speeches. And after controlling for these observer ratings, it turns out that high-anxious folks do indeed have a bit of a “self-evaluation bias.” As in, the more anxious we are, the worse we think we are performing — even if it’s not necessarily true.

It seems that we let the experience of anxiety, and how it feels, affect our perception of how we are performing in the moment. Like having a pair of anxiety goggles which bias how we see the world.

But the thing is, as tight or shaky or nervous as we might be, we can still play at a pretty high level. It might feel like everything is about to fall to pieces in our world, but people on the outside often remain completely oblivious — because we often appear much more at ease and in control than we actually feel.

Take Action

So if you want to avoid triggering the downward spiral of negativity and doomsday thinking, don’t try to evaluate how well you are playing in the middle of a performance. Instead, make sure to record your performance, so that you can give yourself permission to just stay in the moment and play, and delegate all of that judgy, evaluative stuff to future you, when you listen back to the recording.

And maybe don’t dwell on a performance and make yourself feel miserable on the drive home either. Give yourself a day or two to clear your head first, and then listen to the recording. Because if you’re going to beat yourself up about something (not that I recommend it), you should probably make sure it’s about a mistake that really did come across like you thought it did.

As Mark Twain once said:

“I’ve lived through some terrible things in my life, some of which actually happened.”

Don’t stop here!

Continue learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Ryan Lott, and the acclaimed Kiefer: Keys, Chords, & Beats.

—

Performance psychologist and Juilliard alumnus & faculty member Noa Kageyama teaches musicians how to beat performance anxiety and play their best under pressure through live classes, coachings, and an online home-study course. Based in NYC, he is married to a terrific pianist, has two hilarious kids, and is a wee bit obsessed with technology and all things Apple.