+ Soundfly’s Intro to Scoring for Film & TV is a full-throttle plunge into the compositional practices and techniques used throughout the industry, and your guide for breaking into it. Preview for free today!

Because diatonicism is one of the fundamental concepts of Western music. When someone says “something is diatonic,” they’re probably referring to music that sticks to whatever major or minor key it’s written in.

“Happy Birthday” is diatonic. It’s usually played in F major, all the notes are found in F major, the accompanying chords are all chords that are derived from the F major scale.

“Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” is also diatonic, as is “‘Old McDonald Had a Farm,” and Taylor Swift’s “Shake it Off.”

Phew! Another job well done.

Except…

I’m blessed/cursed (blursed?) with an amazing memory for trivial factoids that, once read, take up permanent residence in my hippocampus, like this tenacious memory of a definition of diatonicism I glanced over once in school:

Diatonicism is a scale of 7 pitches, made up of 5 whole steps and 2 half steps, with each of the 2 half steps as separate from each other as can be.

This definition sounds like major and minor scales but… (wait, I’m about to get technical and it’s too early in the article for that) we need some context here.

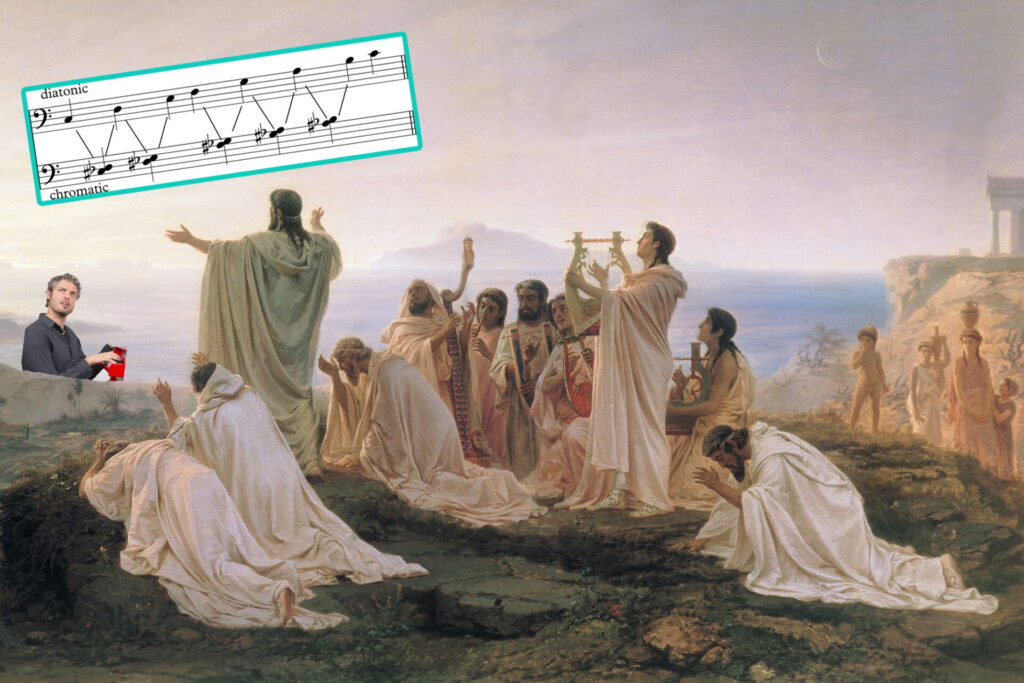

So hold that thought while we go back in time to the origin of Western Music: Ancient Greece.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “An Intermediate Guide to Chord Tones and Tensions.”

The Ancient Greeks were organized.

We owe a lot to the Ancient Greeks’ penchant for organization. Thanks to them, we’re blessed with geometry, democracy, and alarm clocks, as well as the foundations for the tuning system and scales we still use today (and Aeolian harps!).

There’s evidence to suggest that the ancient Greeks had a formal music theory system set up as early as 6th Century BCE, and back in the day music was more than a creative outlet or entertainment, it was a deadly serious science on par with astronomy and mathematics.

Part of the study of music was harmony, although not in the way we understand it today. The Ancient Greeks used something called a monochord to study harmony, which is essentially a single string stretched over a resonant body.

It wasn’t a musical instrument as much as it was a tool for experimenting with the different relationships between pitches.

Like in humans, some relationships between pitches in music are more harmonious than others, and the Ancient Greeks developed a system based upon one of the most harmonious pitch relationships out there: the circle of perfect fifths.

They took pitches created by stacking perfect fifths six times, then organized those pitches in the sequence we recognize as a scale today.

Using this system, the ancient Greeks developed a bunch of modes, which are the ancestors of modern major and minor scales. The name they gave to this collection of modes was “diatonic,” which literally means “through the tones.”

Here, you progress in sequence through a hierarchy of notes, as opposed to the other important scale system invented by the Ancient Greeks, chromaticism, where basically you just play everything.

This is great information, because we can say definitively that the seven “white note” modes are all diatonic. Partly because the inventors defined them so, but also because they all fit the technical modern definition of diatonicism: a scale of 7 pitches, made up of 5 whole steps and 2 half steps, with each of the 2 half steps as separate from each other as can be.

So, therefore, we can assume that all modern major and minor scales are all diatonic too, right?

Lol, no.

Let’s start with the easy part first: all major scales are diatonic. They fit the definition, and also they’re literally one of the Ancient Greek modes — the Ionian mode — which, as we’ve established, are orthodoxly diatonic.

Things get hazy though when we look at the minor scales. There are three kinds of minor scales used in classical Western music: natural, melodic, and harmonic.

The natural minor scale is the same as the Aeolian mode, or the white notes on a piano when you go from A to A. This scale is diatonic, for the same reasons that major scales are diatonic.

The melodic minor scale is a bit borderline, because although it is made up of 7 pitches, with 5 whole steps and 2 half steps, the half steps aren’t as far apart as they can be, because one gap is 5 notes while the other is 2.

Harmonic minor scales though are not diatonic. Not technically.

Harmonic minor scales have the sharped 7th degree, to give the scale a nice clean leading-note necessary for the strong dominant-tonic relationship we expect in Western music. But this creates a gap of a minor 3rd between the 6th and 7th degrees of the scale (well, technically it’s an augmented 2nd, but whatever), and adds an additional half-step.

Harmonic minor scales don’t fit the definition of a diatonic scales, so they’re not technically diatonic scales, like blues scales, whole-tone scales, or whatever scale you come up with when you mash your palm on a random assortment of black and white notes on the piano.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “All (Human) Music Is Repetition — Let’s Talk About That.”

We don’t live in ancient Greece.

Unless something has gone a bit askew in the space-time continuum, you’re not living in Ancient Greece. And, like many things the Ancient Greeks invented, our cultural understanding and use of these concepts has changed a lot over the past 2500 or so years.

(Well, probably not geometry. A triangle to Pythagoras is a triangle to Patrick Stewart).

Diatonicism can refer to scales, in a technical, fussy way, but it also refers to the basic harmonic system we use in Western music, with tonics and subdominants and cadences and all that stuff that’s been around since the time of Bach. And it’s here, I would argue, that the term “diatonicism” actually has some tangible, real world use.

See, there’s a reason why we still use diatonic scales today: it’s a really great system for making emotionally complex music.

Consider chromaticism, the other scalic invention of the Ancient Greeks. All the intervals between all the notes are the same, which means that none of the notes have any particular potency. You can’t call any one note the “root” of a chromatic scale, because you can start anywhere and you end up with the same aural (and therefore, emotional) result.

But diatonicism has this great balance between tension and release because — drumroll please — it’s a scale of 7 pitches, made up of 5 whole steps and 2 half steps!

With those basic details, we can create a whole hierarchy of harmony, starting with the tonic, then the dominant, then adding in the subdominant, relative major or minors, tonic expansions, pre-dominant chords, and then break out of diatonic harmony with borrowed chords, tonicization, half-diminished sevenths, tritone substitutions, Neapolitan sixths… all the wonderful, emotional, heartbreaking, inspiring things that Western harmony is capable of.

All of this stuff is defined by what a member of the general public would understand as diatonicism, which um.. is basically major and minor scales.

I hope you have a lovely day thinking about this.

Don’t stop here!

Continue learning with hundreds of lessons on songwriting, mixing, recording and production, composing, beat making, and more on Soundfly, with artist-led courses by Kimbra, Com Truise, Jlin, Kiefer, and the new Ryan Lott: Designing Sample-Based Instruments.